Spring Breakers Preamble

Thoughts On: Apocalypse Now (Redux)

In a short run up to an exploration of Spring Breakers I want to talk about a couple of 70s classics. I'll be looking at this and then Taxi Driver (possibly something else) for the purpose of looking in on how films can represent an era and the future of cinema. So, without further ado, this quintessential war picture follows Captain Willard through a descent into existential reprieve and postmodern suspension as he journeys up river with the mission to terminate the reportedly insane Colonel Kurtz.

A quick note to begin with, I'm most familiar with the extended (redux) version of this film, it's thematically richer (though a little more chaotic with it's tonal inconsistency), so that's the focus here, but it shouldn't impact much in the way of the film's overall message. If you look at all war films, you can almost always lump them into one of two categories. You have the anti-war films and the pro-war films. The likes of Deer Hunter, All Quiet On The Western Front and Paths Of Glory are quite obviously anti-war. Inglorious Basterds, The Dirty Dozen and even Saving Private Ryan, however, aren't explicitly anti-war. The horrors presented in them may not make war seem pretty, but their tone is quite patriotic and pro-war. Apocalypse Now is the best example of a war film that can't be so easily defined. This is because it doesn't question the need for war, but the need for possession, control and authority - the spoils of war. This film is about imperialism and a quest for perceived power. The best way to sum this film up is to say it's Saving Private Ryan with sense. I don't speak down on Saving Private Ryan here, but the film's philosophical conflict is only ever hinted at, and whilst I don't think the film suffers from that, it does lack the ability to question itself. Both Apocalypse Now and Saving Private Ryan feature a team of men being sent on a mission, through hell, for what are, when questioned, almost pointless, blindly moral, purposes. As said, Saving Private Ryan merely accepts the absurdity as ordered. Apocalypse Now however has the philosophical conflict consume the film as it does the characters. For this reason, when I first saw Apocalypse Now, I felt a little let down. The opening to the film is some of the greatest spectacle and wonder cinema has ever produced, how Coppola conceived and managed such chaos is beyond my imagination. But, with the first 30 minutes the film seems to promise escalating danger and combat. What you come to expect is a huge war, battle or siege on Kurtz's camp in the third act, but that is far from what you get. That can make the philosophical pondering and reading of T.S Eliot quite anti-climactic and, especially to someone versed in war films only with the likes of Platoon, Saving Private Ryan, Jarhead, The Hurt Locker, Black Hawk Down, you're probably going to consider the final act quite pretentious and boring. I've seen Apocalypse Now many times and seeing the first half I could easily say it's the best war film ever made. With the second half however, it almost stops being a war film and so to compare it with others would be pointless.

The second half of this film is actually much more comparable to Aguirre, Wrath Of God, (no, not just because they're going up river) Eraserhead or Taxi Driver. The tone and questions Aguirre, Eraserhead and Taxi Driver hold and force their main characters to face much better give a picture of this film than Platoon, Deer Hunter and most other war films. When you reach the end of Apocalypse Now and try to remember where 'I love the smell of napalm in the morning' and Wagner came from, you could easily think of another film. This, especially with the extended version, is intentional as Willard is passing through the numerous circles of hell. You're not supposed to recognise where you are and where you came from when you get deep enough. As a result this film is a perfect visualisation of the famous Nietzche quote that I won't exhaust - the one with the void. But, before we get into all of that, we need to start off with what the film is about. Apocalypse now is predominantly about imperialism and it's concern with societies and individuals respectively. With imperialism being colonising and taking over land, this film questions the very core symbol of control people hold - countries. The conflict Kurtz and Willard face comes from being pushed to the very edge of human capacity. By knowing true horror, Kurtz finds clarity. The immaterial authority of the army completely falls away from him, as well as his perception of self. This is where we can see the film almost mocking us. The opening act mystifies, excites, enthralls, leaves me in awe, but it does not reveal horror. The best example of this can be seen in Jarhead with the men screening this very film and cheering as the bullets fly and napalm is dropped. War is so easily sensationalised and if cinema teaches us anything it's that we cannot know war's true horrors. Kurtz, in the heat of what we may see as fun is forced into an existential void. By seeing the atrocities of war, he comes to be able to see the complete ineptitude of the army and authority in general. Willard too goes through this with the utter chaos concerning the playmates, lack of C.Os, law, order, sense that bombards him as he trawls his way up the river.

In short, the snail slithering, sliding, along a straight razor blade's edge is humanity - the army and its conduct throughout the Vietnam war. The utter incompetence of the army and soldiers that this film reflects is best portrayed with the journey into the trenches. When we think of Vietnam war films, we think of greenery, thick jungle, ditches, open warfare on a hillside. When we think of World War I or II films we think of trenches, uniforms, control. Coppola's use of trenches in Apocalypse Now allows him to juxtapose his films with those of the 30s, 40s and 50s and also his generation with those previous. If we look at a key WWI film, Paths Of Glory, we can see the utter regiment and control armies were assumed to have. They have the control to do the absurd, the insane, and get away with it. Compare the brilliant tracking shots following Col. Dax through the trenches, men standing to direct attention as he passes them to Willard wandering, stumbling across equally lost soldiers who can only follow apparent orders blindly. War films used to be formations, uniforms and control, steeped in bullets and bombs. That's a world apart from the kind of warfare Copolla puts on screen. By doing this he defines his characters--not just war as a concept--with anarchy or a postmodern sense of loss. Essentially, there's the mindless teens who shouldn't be anywhere nears guns and then there's those who have been mentality tortured into being able to put up a facade of control. It's Kurtz's recognition of this disorder that gives him nightmares of the snail making it across a razor blade - he simply can't believe how the world is getting away with being so disorganised and ruthless. This idea of a relaxed society is what also, in part, defines the generations of the 60s and 70s. Think of 40s and 50s and you think of suits, ties and fedoras. Think of the 60s and 70s and you get crazy hair, huge open collars, and blinding colors. The western world obviously changed a lot in 60s as anyone who's taken a history class will be able to tell you a lot better than me. Coppola, using his characters, not just the situation of war, explores this era of postmodern questioning.

Postmodernity, in a very general sense, tries to accept the chaos of the world without trying to define it. With a postmodern mindset as supplied by having everything he knows contradicted by witnessing pure horror and a lack of control in governing bodies, Kurtz sees all people as people, no hierarchy. And in a world without a concept of organisation, it can't be hard to see yourself as a God. This is linked to the idea of grown up. In the same way we grow to see our parents as people and our perception of 'adult' shifts, Kurtz almost matures beyond the idea of authority. Generals, colonels and the army has been leveled out to a group of people who simply don't know what they're doing to him. Kurtz, the perfect soldier, sees himself as a step above the army in the same way a teacher of a class of 6 year olds would. If you collapse a school system, all society, around that teacher and her class, well... you can imagine the power trip she'd endure. In fact, this is exactly what Willard goes through by getting up the river. The men around him, the soldiers he meets, the organisation that commands them, all fall flat on their face, then laugh as they pick themselves up, caked in mud, looking pretty ridiculous. In short, Willard loses all respect, leaving the only person who he believes to be on his level to be Kurtz himself. But, upon meeting him, Willard learns that Kurtz is nothing more than human and that the authority he holds is over nothing more than the mindless and insane. I mean, his biggest follower is the hippy journalist and... yeah... that doesn't look good. So, Willard finds the power, the authority, to kill Kurtz and abandon society. But, one thing remains--and that is the army. Kurtz and Willard abandon the army, they do not rise above it. What they do is the equivalent of walking away from an argument with a stupid person because they know they can't win. However, 'stupid' is what beats Kurtz. The army wins in the end. Despite Kurtz's transcendental experiences, he loses sight of himself. In the end he wants to 'go out like a soldier'. When the void stares back at Kurtz he's probably left wishing he hadn't assumed the power he found for himself. This is the choice Willard faces in the end of the film. He has no respect for the army, has defeated his only equal and stands before an army willing to bow at his feet. But he walks away. He refuses to assume power.

What Apocalypse Now explores is the unfathomable concept of control. In truth, people don't have much. But that we see ourselves as having manifests itself through the idea of organisations--countries. Kurtz and Willard alike take journeys towards being able gather the capacity and power to become imperialists--to start their own countries. We never know, but had Kurtz been consumed completely by the control he finds for himself, he could have continued to take over villages, chunks of land, build a bigger and bigger army made up of more competent soldier's that would help him win the war, and, who knows? Take over the country. Kurtz as a dictator could be capable of unthinkable anarchy. But, is that spin off you're dreaming of right now in any way feasible? In any way realistic? Is there any plane of verisimilitude big enough to allow such a thing to happen? This is the question that halts Kurtz's operations, that makes Willard walk away. In short, humanity is that snail and it makes it's trip across the razor blade daily--no sweat. Credit given where credit due, humanity deserves a round of applause. The message Kurtz, that the film, wants to give to the world - Kurtz to his son - is that people can do no better than to be themselves. Kurtz doesn't kill Willard for the hope that he will tell his son his story--no lies, no fabrication. He doesn't believe he is bad, evil, corrupt, but that he's found clarity. And if you can stretch your mind into the realm of postmodernism you could easily agree with him. By seeing authority as nothing more than a figment of our imaginations we can sympathise with Willard's and Kurtz's struggle alike. They face what we daren't - the void. But, with clarity comes the idea that it will all end, not with a bang but a whimper. If you aren't familiar with T.S Eliot's Hollow Men, you can read it here if you like. But to summarise roughly, Eliot sees the heartless and empty men of the world, it's leaders--the faceless and nameless organisations--as inevitably doomed. Eliot's poem is aimed towards the likes of the Kurtz character as presented in Joseph Condrad's Heart Of Darkness (which the film was adapted from) and explains why he's mentioned in the epigraph. Eliot, with the Hollow Men, shows imperialists and those who claim the title of God, to be corrupted and the inevitable cause of the sorry end to humanity if they are allowed to keep their power. Eliot probably sees ultimate power in the hands of God himself (herself? itself?) and so sees imperialism as a form of heresy or blasphemy as one is comparing themself to Him/Her/It.

To offer an alternative explanation in the guise of a film that doesn't rely on religious themes, it seems that any leaders can be considered Hollow Men. The more power you take on, the more hollow, the less human, you become. In short, by seeing yourself as God, by assuming you have control, you dehumanise yourself. Humans, as a species are inevitably going to cease to be one day. The most likely cause to this is through the expense of all our resources and environment. I'm not going to make any specific speculations as to the end of humanity though, merely point out the fact that, by natural law, all species rise, peak and inadvertently kill themselves. Just look at bacteria or yeast cells. If you contain a small population in a sample with a good supply of nutrients, they'll use it, steadily, then rapidly increasing their population. All the while they'll respire, producing CO2 or other toxic byproducts. With population increase comes pollution and ultimately death. Humanity's petri dish is Earth and we could be on that steep slope toward peaking in population and starting to kill ourselves off with our self-pollution. Morbidity slightly to the side, to have control inside this doomed system is to assume responsibility for that end. Whether it's under a country, government, monarchy, dictator, someone's going to have to be the last person to whimper. By transcending authority Kurtz's and Willard see this future and they feel this weight of responsibility. This is why they hit self-destruct. A bang before a whimper, if you'll have it. Apocalypse Now, along with a few other 70s masterpieces really pushed the bounds of cinema in a way that no one has managed since. I know when talking about Adventures In Babysitting I made contradictory statements concerning the power of cinema--and I in no way retract anything I said. But, what I mean here is that Apocalypse Now represents a type of thinking that is not present in the zeitgeist of today. Cinema peaked in the 70s in terms of postmodernism and existentialism and has very quickly immatured. But, that's a talk for another time and another film.

All in all, Apocalypse Now cites the weight of responsibility, the capacity for any man to see himself as God and reject authority, but ultimately shows that to try and rule the world, one must face the self-destruct button. What it communicates is the irrevocable chaos in 'organised' systems, and how if we think things should change, we should first ask ourselves if we could change them. In short, could you, the snail, make it to the end of the razor blade alive?

Thoughts On: Taxi Driver

With a continued look in on 70s classics before looking at Spring Breakers I come now to what could be Scorsese's best film. I started with Apocalypse Now and will be looking at One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest next, with the intentions of exploring the ways in which cinema has changed over the last 40 years, and what the current era of cinema will be defined by. So, Taxi Driver follows an insomniac and a loner, Travis Bickle, through the streets of New York as his disdain for the city and world festers, culminating in an explosive gesture for catharsis and an attempt towards fixing his broken world.

Taxi Driver is the quintessential 'man with a problem' picture. Some like to look down on this kind of film. One of Christopher Nolan's key criticisms is that he tells the same 'man with a problem' stories. From Memento, to The Dark Night, to Inception, his male leads lose the women dear to them and then battle an internal struggle against the loss. Such stories are criticised because women are seen to be objectified, reduced to mere motivation instead of real characters. With 8 1/2 I explore what this is and why it's done. In short, films are dictated by character's perception. But, the main argument against the 'man with a problem' film usually pertains to a question of, why aren't there many 'woman with a problem' pictures? I think this is a genre, or grounds, that cinema hasn't explored too well at all. This may be down to fact that if I were to name a handful of the greatest directors of all time, without prejudice, I wouldn't come up with one woman. Google the 'best directors' and you get Scorsese, Spielberg, Nolan, Fincher, Tarantino, Hitchcock, Ridley Scott, Kubrick, Coppola, Cameron, Eastwood, P.T.A, Woody Allen, Tarkovsky, Rossellini, Goddard, Truffaut, Fellini, Bergman, Ozu, Kurosawa, Lynch, Cronenberg, Bertolucci, Chaplin, Peckinpah, Welles, Leone, Aronofsky, Capra... the list literally goes on and on and on. You don't get a woman until Sophia Coppola, Katheryn Bigelow or Ava DuVernay - and they are way down on the list. This is a very depressing and ultimately confusing reality. I won't pretend that there is one cause to this paradigm, or pretend to know the solution to the problem. But, when looking at Taxi Driver in this respect, you're faced with some difficult questions. Could Travis have been a woman? Yes, of course. But would the film have been as successful? As poignant? I feel the answer is no. The film would have been reduced to an exploitation or 'feminist' picture. Ridley Scott is praised for using characters like Ripley or Thelma and Louise. But, that idea is quite counter productive. Having strong female leads is the equivalent to having 3D in your film. It doesn't instantly make it better, but triggers an audience's interest. I won't delve too deep into these questions here, instead, save it for the talk on Spring Breakers--which I might end up splitting into several parts. What is relevant about the idea of a 'man with a problem' is Travis' issues being universally applicable.

Taxi Driver is about loneliness and authority. Anyone can face such issues, but Travis' retaliation is stereotypically male. The dynamic and tone of this film is reliant on the existence of this idea of a man with a problem and a stereotypical male response. Travis' underlying struggle with loneliness comes with his inability to get along with women and their rejection of him. We can see Travis' fight against societal ostracisation primarily with women, with Betsy and Iris. How Paul Schrader describes the film is as paraphrased: Travis is a guy who wanders around, he can't have the woman he wants and he doesn't want the woman he can have, he then tries to kill the father figure of one and fails, but does manage to kill the father figure of the other and becomes a hero. This is the best thematic summation of the film I've heard--and rightly so, Paul Schrader wrote the film. Travis, as he says, is God's lonely man. But, again using Schrader's view of the film and his intentions, people aren't born lonely, 'we make ourselves lonely'. Those three ideas are the crux of the film. Firstly, there's the problems with women, second is loneliness, third is responsibility. Problem, effect, retaliation. We learn of Travis' problems with direction and of course his narration. Scorsese made a point of directing this film from Travis' point of view, only ever once showing what Travis wouldn't have seen - the scene with Iris and Mathew dancing. We are made to cruise the grimy, grim, ill-lit streets of New York, constantly privy to crime and poverty so that Travis can be further isolated. The blurred and distant lights of the world beyond his cab imply his disconnect and when he opens the door to customers he's letting in more than potential fare. He's relinquishing control and letting in danger. The 'Taxi Driver' is an archetypal character of a person who lives as part of a city. And when that city is dangerous, they are show to be living life on the edge. This is why the archetype is applied to Travis' character. It perfectly captures both his will to be apart of society, but ultimately reduces him to a piece of furniture. This is also Travis making himself lonely. His problems and their effects are looped in positive feedback.

The idea of problems that reaffirm themselves by the actions they induce in us is a very telling paradigm. Almost all of the major issues faced by humanity are manufactured and self-preservative. People decide to go to war, choose to pollute, corrupt, lie, steal. As a whole, humanity is incapable of stepping out of this cycle of causing problems and feeling their burn. Travis' inability to hold onto relationships deepens the commentary. Coming back to women, Travis wants a girl that may be beautiful, but who ultimately isn't much like him and isn't that interested. When he comes across Iris, he comes across a character very similar to himself. She chooses to be a prostitute, to stay with Mathew. She can never step out of the loop. Travis could have easily been with her if he could bypass his own moral sense. But, like almost all of us, he can't - he doesn't sleep with a 12 year old. Women, in this respect, represent Travis' natural urges. But, his morals, standards that are too high and his persona disallows him to adhere to his natural inclinations in a true, or satisfying, sense - yes, he can go to porn theatres, but can't win Betsy over. Why? Because he messes up by taking her, on their first date, to see a porno. He allows himself to destroy what he wants. Porn represents an easy fix. Travis fits into an unfortunate niche here. He's willing to accept the easy fix that isn't good enough (a sticky seat in a porn theatre) whilst refusing another equally easy fix that may be more satisfying - Iris, otherwise known as Easy. Travis' conflict is himself, is this idea of morals. Morals are apart of what makes people human - it's what separates us from the animals. But, humanity is as much a gift as it is a task. Is self-awareness, conscientiousness, are feelings, emotions, really that great? Without them life would be an automated process, not a struggle to balance opposites: love, hate; need, want; society, individuality; us, them. But, the solution to the problems of humanity is not as simple as hitting auto-pilot. Our response to war, corruption, pollution, lies, theft, poverty, inequality, comes in the form of government, democracy, hierarchy, morals, social norm and laws. This idea is expressed though the political elements of this film, but ultimately comes back Travis and women.

Humanity is not perfect despite government, democracy, such and so on. This gives reason as to the state of New York in Taxi Driver and Travis' disdain. Don't worry, I'm not going to go into the historical and political atmosphere of the late 60s and 70s - this is partly because that's a small feature of the film, but mostly because I wouldn't know what I was talking about. With the wold being imperfect, Travis wants change. He sees a failing solution, a lie, in Palantine (the politician) and a worsening and ever prevalent situation around him as expressed through Mathew (the pimp). As Paul Schrader says, to Travis, these are 'father figures'. Travis isn't at all concerned with politics, but the girl at the politician's head quarters. Travis isn't so much concerned with the combatance of drug and gang crimes, neither prostitution. He simply wants a rain of biblical proportions to wash them all away, flush them down the toilet. His reasons for engaging in the final conflict are selfish, just as the reason why he didn't assassinate Palantine was. By killing Palantine, Travis wouldn't have won, spited, or helped Betsy. And so, he was quick to give up on the pursuit of what can be considered an authority figure above her. Killing Mathew and the organisation around the pimp is the only way Iris could escape her cycle. But, she's 12, Travis has no sexual inclination to save her. Travis, as a loner, may only break the cycle of his own pain by ending his life with the alleviating idea being that he died for a good reason - saving Iris. In short, in self-pity, Travis decides to affect the world the only way he knows how. There's a little more to the ending of the film though. The reasoning behind all the destruction comes with an idea of retaliation to authority. Travis makes himself lonely by telling himself the world is disgusting, that there is no solution to its problems beyond washing it all away and starting again. The final conflict is not representative of Travis washing away the problems of the world, but his problems with the world. He allows himself to see Mathew as the symbol of all that is wrong in his city. When he destroys that symbol, he's rewarded, but is ultimately left the same person. Travis has metaphorically washed out the streets of New York and in the end of the film, with him coming across Betsy again, he's reminded that he's merely displaced its issues - just like he has his own.

This idea links to Travis helping the girl he does not want. Here's the sad reality of the film. Travis was in the papers, Iris is safe, but all will probably be forgotten, Iris will probably hate school and would have only adopted a whole new set of problems. How easy would it be for a 12 year old former prostitute to fit in with other girls? Her problems, like his problems, have been displaced, not solved. The true happy ending to the film would have been some wishy-washy transformation which allowed Travis to get Betsy. But, hold on, that's not exactly true. How well do you think their marriage would go? Not very well at all. Travis was doomed from the beginning. He is the type of man that will probably forever be stuck in a cycle of his own issues. This is why Scorsese made the film. He thought it was a form of maturity, that it was ok to have the feelings of hatred Travis had, but not to cross the line he did. Taxi Driver asserts that some times it's not the world that needs to change, but your view of it - and that you can't go killing the fathers of the women you like because they represent a wall. It's Palantine that represents democracy and a sense of control in Betsy that Travis (as a person who ultimately devolves into an anarchist) can't get along with. It's Mathew as an immoral dreg of society that represents why Travis can't have Iris. In short, to be with those women he must be like them, be like their father figures. It's Travis' isolation from society, from other men, that makes him incapable to behaving like them. That is why this is a 'man with a problem' picture. It centres around the world of men with themes of not belonging. It's because Travis isn't the stereotypical man that he can't get the women he wants. By adapting the downfalls of the stereotypical man however (aggression, violence) Travis only recycles his descent--furthering himself from the idea of an average man and getting the women he desires. This speaks to the film's bigger picture which deals with the conflicts of humanity. In the same way Travis dooms himself, we shouldn't want to 'fix' the problems with humanity. We shouldn't be looking for the auto-pilot button. Problems must be dealt with internally, not externally. War? Everyone decides they don't want to kill or be killed and it won't happen. Pollution? Everyone decides they care about the future of our environment and they wont' actively harm it. The same goes for any and all major issues humans have made for themselves. But, alas, the major issue is humanity and me asking everyone to change, too look inside themselves, is just as futile as shooting up a crack den--no matter how good it makes me feel or how others praise me.

All in all, Taxi Driver is about responsibility. It's about taking your issues and dealing with them internally, not trying to project them onto the world around you and then asking or forcing it to change. The person that you should be asking 'you talking to me?' is not any figure of authority, of power, of opposition. No, you save the question for the mirror and maybe one day your refection will talk back, they might say 'yes, let's having a conversation'. Whether you shoot at them or not is up to you, but remember, the gun's not loaded.

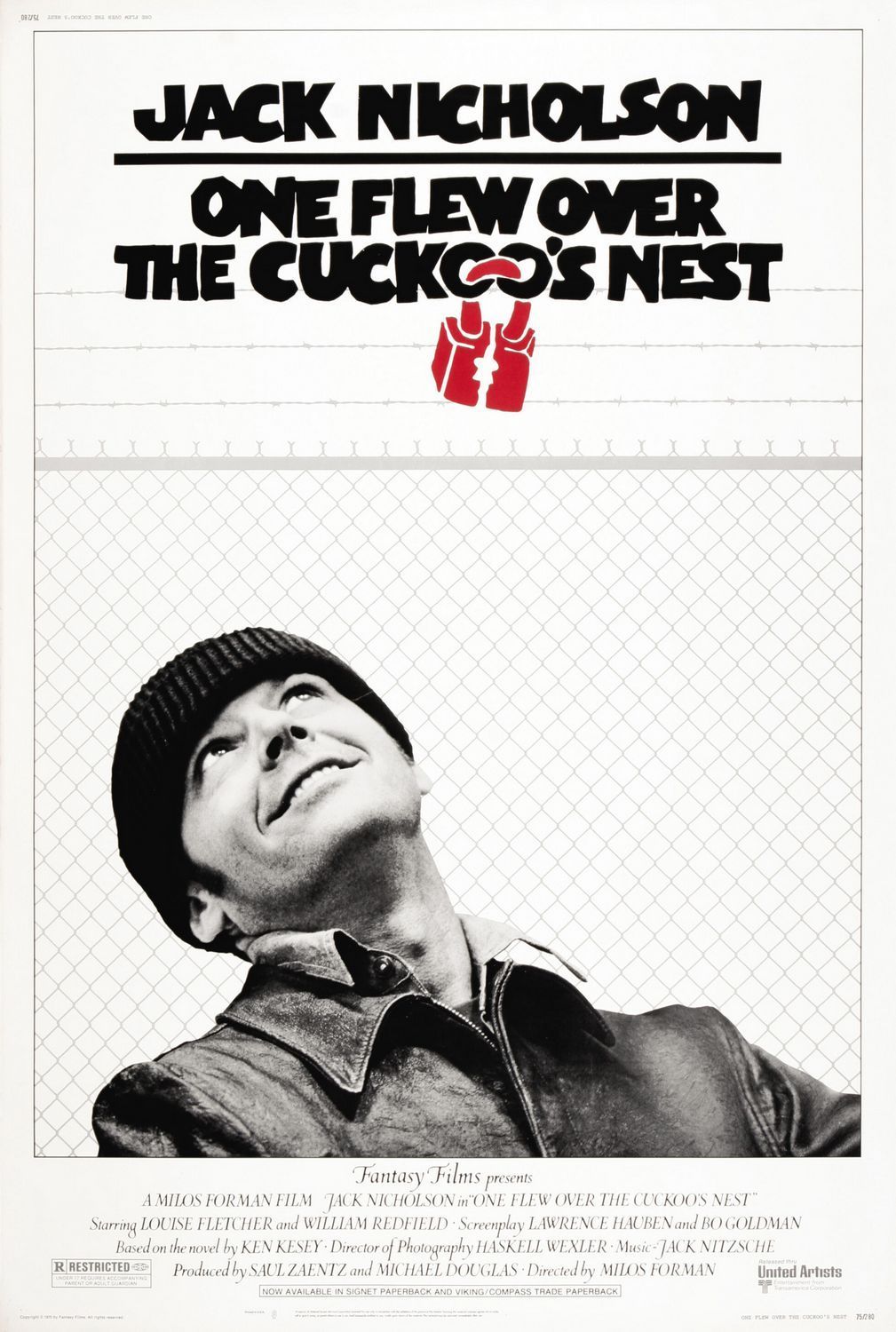

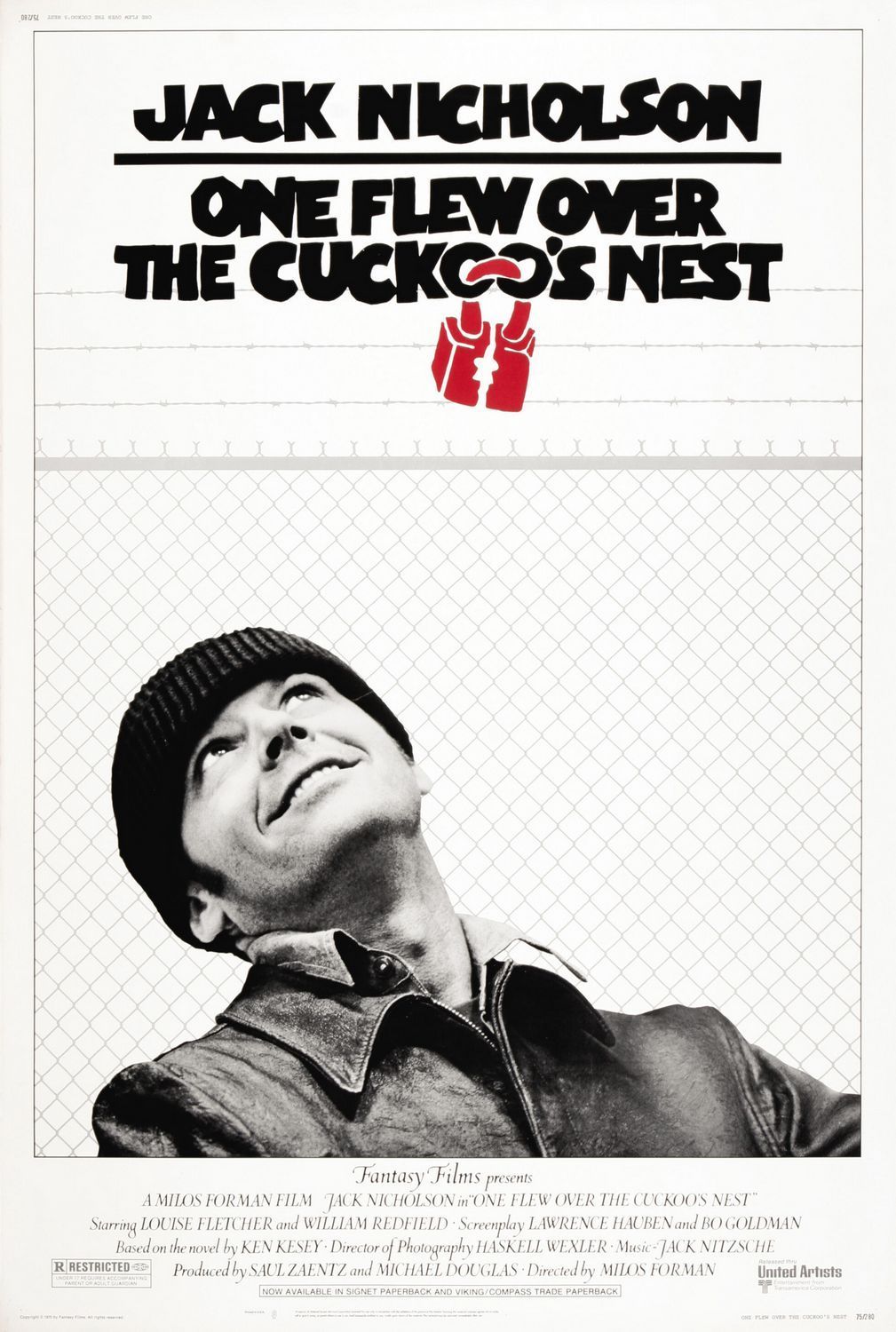

Thoughts On: One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest

The last 70s classic I'll be looking at before diving into Spring Breakers. This follows Randle McMurphy into a mental institution, where he discovers the life of a psychiatric patient isn't so mellow and free.

This movie, despite the end, is one of the most joyous films of all time. It does this by perfectly balancing the idea of chaos with control and restraint through mischief. Jack Nicholson perfectly captures a person with little restraint, little self-control, but an abundance of respect and heart. It's because Randle only wants to enjoy himself that he can rouse a sense of humanity and normalcy in those others would consider insane. In short, Randle only wants to see the likes of himself in others and so can see character beyond facade. This is ultimately how we see and is what makes this film absolutely phenomenal. Whilst the film does have themes and questions surrounding a question of normality versus insanity, I won't be focusing on them today. What we'll be looking at is is the two core ideas of the film. The first is chaos and disorder for the sake of levity or fun. The second is trapping yourself and being trapped. Let's jump right into what Randle represents. He is the part of you that picks up snowballs even though you know you're hands are going to get cold, wet and probably to the point where you're almost in tears. Randle is what makes you put glue or sticky tape in your friend's hair for a laugh. You've ruined their day, possibly the next month of their life, but, shit it was funny. Impulsiveness and good intent laced with apparent malice, this is Randle. I mean, just look at that smile up there... I need say no more. How he explains himself as the chaos factor to an organising body (the psychiatric hospital) is that he fights and fucks too much. He is, for all of those who've taken a psychology class, representative of the id - instinctively drawn to innate impulses. Law's purpose is to essentially control that part of society. But, with ease, Randle can have Dr. Spivey smiling over the idea of statutory rape and the audience cured of any disillusion. This has quite a bit to do with antiheroes, but Randle's case is quite special. Sex driven teens are quite the norm, as are gangsters, murderers, monsters and idiots. All common antiheroes. What Randle manages to be is an amalgamation of Travis Bickle and Alex DeLarge. This comes back to what makes the film special. Randle is the dark antihero, your Batmans, Charles Foster Kanes, Jim Starks, or Men With No Names. At the same time he's a Patrick Bateman, Juels Winnfield, Joker, Sugar Kane Cowalczyk, Jordan Belfort. There's a very strong sense of of both ying and yang in his character that few others can manage.

Whereas The Joker can get away with beign 90% bad but 10% truly entertaining, Randle splits the divide evenly because One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest ultimately isn't about bad trumping good. This film is made up of antiheroes and the naive. Nurse Ratched may seem like an antagonist, but with an antihero in a realist picture, she can't be the bad guy, but a representative of Randle's opposite. She may act in opposition to him, but not in hostile way, and so, she's not a true antagonist. This will eventually link into trapping oneself and being trapped, but the first takeaway here is that of balance. When we take into consideration all sides of character motivation, the film asks how much control an institution should have. This is best summed up with the cigarettes ordeal. All patients have their cigarettes rationed and doors locked because they essentially aren't trusted to look after themselves. Because Randle won all their smokes, Nurse Ratched decides to look out for her patients and stop what she assumes to be cheating from happening--just like countries may make gambling illegal. But, as Manchini says, how, without their cigarettes, will they win any back? To control we must minimize risk. But risk, the whole concept of odds and imbalance, is meant to excite a system, both in an emotional and physical sense. The freedoms of being an adult are best utilised by those trying to do something childish and stupid. Mistakes are seen as a right to an individual, but on a larger scale, mistakes are big no, nos. Randle is chaos, Nurse Ratched is control and we are the likes of Martini, Taber and Cheswick. We are the impressionable. I like to say this too much, but, the crowd is the stupidest person of all. They can be lulled into routine or sparked into chaos like a child with ice cream; refuse to give it to them, they scream, give it to them, they love you, they drop it, they scream again, give them another, they're grinning again. This kind of makes Randle the big kid who'd happily smack the ice cream out of your hand and Ratched the parent who warned you not to drop it. But, ice-cream and tears are trivial matters. What the film is more concerned with is the over-reactions, the misunderstandings. In the same way Taber shouldn't have been detained because a cigarette burnt his foot, Nurse Ratched didn't deserve to be strangled. At the same time, I don't think Randle really needed lobotomising either. But, the question raised is, who would? Are the over-reactions always unjust?

The conflict between control and chaos in a liberal or moral society--liberal more so--is tantamount to embarrassment. With rules such as freedom of speech, people are forced into a corner when they hear something they do't want to. People and idealism don't work together because people hate contradiction, but love to say we're all human. The cycle is quite funny to me. As a species humans yearn for paradigms - formulas that make us all happy. But, one of the worst attempts at this is the idea of doing onto others as you'd want done onto yourself. Equality is one of the key ideals of our day and age, the idea is prospectively warming, but when faced at present isn't always so fun. Equality is sharing your toys with that snot nose kid that got away with making you eat sand. Equality is staring the nurse who just drove your friend to suicide in the eye and saying, well, I'm sure you didn't mean for that to happen. Equality is blind tolerance, blind forgiveness. Why should we love our enemies? Yes, I can pragmatically say that Nurse Ratched didn't deserve to be strangled, but had I stood in Randle's shoes, like almost all of us, I could have strangled the bitch. Maybe I wouldn't, but I could not forgive her so easily. This is the embarrassing state of conjecture. We love to ignore apparent truths or what makes us look bad so we can get those retweets, that round of applause from strangers. Here's one I love, 'treat your girl like a queen and you become a king'. I see it all the time, but, no, simply, no. All that sounds like to me is an abusive relationship. But, it keeps the girls smiling and the guys' hopes of sticking it in you high--so, shh. From a literal perspective, people love to spew nonsense and this translates to the film's ideas through its main conflict. Both Randle and Nurse Ratched are trying to look out for the patients at the psychiatric hospital. Randle, for fun. Nurse Ratched, because it's her job. Both for moral comfort in helping others. The patients maybe need parties and alcohol as much as they do therapy and pills. Both sides of the spectrum (Randle/Ratched) don't want to accept this. The true tragedy in the end of this film is not that Randle is reduced to a zombie, but that the film had to end, that things got so out of hand. The reasons for this link to the second idea of the movie.

Whilst this is a film about freedom, it is as much about about enslaving oneself. It's because of Randle's, what he would call, misdemeanors, that he was sent to prison. However, in an attempt to cheat the system and get an easier ride, he gets into the psychiatric hospital. Because of his nature, he ends up trapped in a place that he doesn't seem to belong--but kinda does. In this sense Randle is just as much of a voluntary patient as Billy. This isn't so coherent in the beginning of the film, but by the third act all is revealed. It's the lingering close-up of Randle having just set Billy up with Candy that shows that he doesn't want to leave for Canada. He puts on a relaxed facade, but can't prevent his embarrassment from surfacing in his disingenuous smile to no one. Randle chooses to stay until morning, just like he chose to put the keys back on the window ledge. Chaos is nothing without control and all Randle was looking for was a fight. It's the in-extreme element, the mid-ground, that suffers from this. Like I said, there's the antiheroes and the naive. When extremists fight for control, the crowd that watches is torn left to right until they break. This is what happens with Billy. It's unclear whether Ratched or Randle is better for him, if routine or impulisivity better suite his nature, but both of them together prove fatal. In the same way that Billy is torn apart, that Randle tears himself apart by rebelling, systems are shown to collapse by not managing their extremes. In short, opposites are rarely equal in a literal sense. Someone always has to win. Unstoppable forces do not meet immovable objects. Randle is a binary archetype, it's all or nothing, off or on, with him. As with Ratched. What does this imply? It implies that we should all become more tolerant, backpedal toward a mid-ground, toward equality. Contradiction! I hear you scream. Well, yes. But, here's the thing, a move toward equality is not equality. Systems, like people, work best when in conflict. This is the crux of the film (I feel like this is becoming a catchphrase). Anyway, the core idea of the film is not in Big Chief running toward the horizon, free as an eagle, big as a mountain. The point is lifting that sink and breaking the window.

Conflict is what the film ends on, is what the film implores. It's with imbalance, Ratched in the nurses station with a neck brace on, the group playing with a set of cards with nude women on, but Randle nowhere to be seen, that the film finds peace. It's Randle when, having lost the vote, can sit in front of a blank screen a yell like a child, that the film finds joy. It's when Cheswick is moaning, 'Hard-on' is ranting, Martini's giggling, Taber's mocking, Sefelt yips 'peculiar!?' and Billy silently grins, that morbid silence can't stagnate, that everyone seems so alive. This is why we trap ourselves in jobs we don't love, with friends that are annoying, with people who don't share our ideals. Not, only do we love to moan, but we need conflict to know that things are happening. This is where the rolling stones and underwear aphorisms come into play. Rolling stones plow through life. Not gathering moss is refusing to, as Ferris Bueller would say, stop and take a look around once in a while. In the same respect not cleaning your dirty underwear in public is best defined with the Kim Jong-un character in The Interview. It's refusing to be seen as human--to have a butt-hole. Randle is a rolling stone, Ratched wouldn't wash dirty underwear in public. They are flawed in the same sense because those they aim to impress themselves upon are never truly allowed to see them as much more than caricatures. Randle's happy to throw a big gestures, but rarely small ones. Ratched exercises restraint to the point of being nothing more than cold. By polarising themselves they are trapped in conflict with each other, but a conflict that'll always want to escalate. A conflict that has an end, wants to stop and have the life sucked out of a place. However, with Big Chief, Randle found another opposite. He's controlled internally, but he does not want to control externally. It's these two that form the most genuine relationship, that can have the quiet conversations. And so, through Chief, a part of Randle lives on. One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest is ultimately about inserting the right amount of chaos into a control system so that it can thrive. The hard conflict the film endures cites an unbalanced imbalance. The levity we are given through joyous uproar is the porridge that's not too sweet, not too salty, but just right. Of course, we're stealing from bears, but everyone loves a fairytale, adventure, a bit of danger.

All in all, One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest is about the world as a 'Cuckoo's Nest'. Yes, Cuckoos are birds--they are free--but they're nuts. And so again, the tragedy of the film is not that Randle flew over the nest, but that he couldn't stay. Chief, in all hope, hasn't fled the nest, but entered a bigger badder world. Ultimately, freedom is not shown to be in peace, but in comfortable conflict--the tears and the ice-cream. If the world wasn't a crazy place, then what would it be?

In a short run up to an exploration of Spring Breakers I want to talk about a couple of 70s classics. I'll be looking at this and then Taxi Driver (possibly something else) for the purpose of looking in on how films can represent an era and the future of cinema. So, without further ado, this quintessential war picture follows Captain Willard through a descent into existential reprieve and postmodern suspension as he journeys up river with the mission to terminate the reportedly insane Colonel Kurtz.

A quick note to begin with, I'm most familiar with the extended (redux) version of this film, it's thematically richer (though a little more chaotic with it's tonal inconsistency), so that's the focus here, but it shouldn't impact much in the way of the film's overall message. If you look at all war films, you can almost always lump them into one of two categories. You have the anti-war films and the pro-war films. The likes of Deer Hunter, All Quiet On The Western Front and Paths Of Glory are quite obviously anti-war. Inglorious Basterds, The Dirty Dozen and even Saving Private Ryan, however, aren't explicitly anti-war. The horrors presented in them may not make war seem pretty, but their tone is quite patriotic and pro-war. Apocalypse Now is the best example of a war film that can't be so easily defined. This is because it doesn't question the need for war, but the need for possession, control and authority - the spoils of war. This film is about imperialism and a quest for perceived power. The best way to sum this film up is to say it's Saving Private Ryan with sense. I don't speak down on Saving Private Ryan here, but the film's philosophical conflict is only ever hinted at, and whilst I don't think the film suffers from that, it does lack the ability to question itself. Both Apocalypse Now and Saving Private Ryan feature a team of men being sent on a mission, through hell, for what are, when questioned, almost pointless, blindly moral, purposes. As said, Saving Private Ryan merely accepts the absurdity as ordered. Apocalypse Now however has the philosophical conflict consume the film as it does the characters. For this reason, when I first saw Apocalypse Now, I felt a little let down. The opening to the film is some of the greatest spectacle and wonder cinema has ever produced, how Coppola conceived and managed such chaos is beyond my imagination. But, with the first 30 minutes the film seems to promise escalating danger and combat. What you come to expect is a huge war, battle or siege on Kurtz's camp in the third act, but that is far from what you get. That can make the philosophical pondering and reading of T.S Eliot quite anti-climactic and, especially to someone versed in war films only with the likes of Platoon, Saving Private Ryan, Jarhead, The Hurt Locker, Black Hawk Down, you're probably going to consider the final act quite pretentious and boring. I've seen Apocalypse Now many times and seeing the first half I could easily say it's the best war film ever made. With the second half however, it almost stops being a war film and so to compare it with others would be pointless.

The second half of this film is actually much more comparable to Aguirre, Wrath Of God, (no, not just because they're going up river) Eraserhead or Taxi Driver. The tone and questions Aguirre, Eraserhead and Taxi Driver hold and force their main characters to face much better give a picture of this film than Platoon, Deer Hunter and most other war films. When you reach the end of Apocalypse Now and try to remember where 'I love the smell of napalm in the morning' and Wagner came from, you could easily think of another film. This, especially with the extended version, is intentional as Willard is passing through the numerous circles of hell. You're not supposed to recognise where you are and where you came from when you get deep enough. As a result this film is a perfect visualisation of the famous Nietzche quote that I won't exhaust - the one with the void. But, before we get into all of that, we need to start off with what the film is about. Apocalypse now is predominantly about imperialism and it's concern with societies and individuals respectively. With imperialism being colonising and taking over land, this film questions the very core symbol of control people hold - countries. The conflict Kurtz and Willard face comes from being pushed to the very edge of human capacity. By knowing true horror, Kurtz finds clarity. The immaterial authority of the army completely falls away from him, as well as his perception of self. This is where we can see the film almost mocking us. The opening act mystifies, excites, enthralls, leaves me in awe, but it does not reveal horror. The best example of this can be seen in Jarhead with the men screening this very film and cheering as the bullets fly and napalm is dropped. War is so easily sensationalised and if cinema teaches us anything it's that we cannot know war's true horrors. Kurtz, in the heat of what we may see as fun is forced into an existential void. By seeing the atrocities of war, he comes to be able to see the complete ineptitude of the army and authority in general. Willard too goes through this with the utter chaos concerning the playmates, lack of C.Os, law, order, sense that bombards him as he trawls his way up the river.

In short, the snail slithering, sliding, along a straight razor blade's edge is humanity - the army and its conduct throughout the Vietnam war. The utter incompetence of the army and soldiers that this film reflects is best portrayed with the journey into the trenches. When we think of Vietnam war films, we think of greenery, thick jungle, ditches, open warfare on a hillside. When we think of World War I or II films we think of trenches, uniforms, control. Coppola's use of trenches in Apocalypse Now allows him to juxtapose his films with those of the 30s, 40s and 50s and also his generation with those previous. If we look at a key WWI film, Paths Of Glory, we can see the utter regiment and control armies were assumed to have. They have the control to do the absurd, the insane, and get away with it. Compare the brilliant tracking shots following Col. Dax through the trenches, men standing to direct attention as he passes them to Willard wandering, stumbling across equally lost soldiers who can only follow apparent orders blindly. War films used to be formations, uniforms and control, steeped in bullets and bombs. That's a world apart from the kind of warfare Copolla puts on screen. By doing this he defines his characters--not just war as a concept--with anarchy or a postmodern sense of loss. Essentially, there's the mindless teens who shouldn't be anywhere nears guns and then there's those who have been mentality tortured into being able to put up a facade of control. It's Kurtz's recognition of this disorder that gives him nightmares of the snail making it across a razor blade - he simply can't believe how the world is getting away with being so disorganised and ruthless. This idea of a relaxed society is what also, in part, defines the generations of the 60s and 70s. Think of 40s and 50s and you think of suits, ties and fedoras. Think of the 60s and 70s and you get crazy hair, huge open collars, and blinding colors. The western world obviously changed a lot in 60s as anyone who's taken a history class will be able to tell you a lot better than me. Coppola, using his characters, not just the situation of war, explores this era of postmodern questioning.

Postmodernity, in a very general sense, tries to accept the chaos of the world without trying to define it. With a postmodern mindset as supplied by having everything he knows contradicted by witnessing pure horror and a lack of control in governing bodies, Kurtz sees all people as people, no hierarchy. And in a world without a concept of organisation, it can't be hard to see yourself as a God. This is linked to the idea of grown up. In the same way we grow to see our parents as people and our perception of 'adult' shifts, Kurtz almost matures beyond the idea of authority. Generals, colonels and the army has been leveled out to a group of people who simply don't know what they're doing to him. Kurtz, the perfect soldier, sees himself as a step above the army in the same way a teacher of a class of 6 year olds would. If you collapse a school system, all society, around that teacher and her class, well... you can imagine the power trip she'd endure. In fact, this is exactly what Willard goes through by getting up the river. The men around him, the soldiers he meets, the organisation that commands them, all fall flat on their face, then laugh as they pick themselves up, caked in mud, looking pretty ridiculous. In short, Willard loses all respect, leaving the only person who he believes to be on his level to be Kurtz himself. But, upon meeting him, Willard learns that Kurtz is nothing more than human and that the authority he holds is over nothing more than the mindless and insane. I mean, his biggest follower is the hippy journalist and... yeah... that doesn't look good. So, Willard finds the power, the authority, to kill Kurtz and abandon society. But, one thing remains--and that is the army. Kurtz and Willard abandon the army, they do not rise above it. What they do is the equivalent of walking away from an argument with a stupid person because they know they can't win. However, 'stupid' is what beats Kurtz. The army wins in the end. Despite Kurtz's transcendental experiences, he loses sight of himself. In the end he wants to 'go out like a soldier'. When the void stares back at Kurtz he's probably left wishing he hadn't assumed the power he found for himself. This is the choice Willard faces in the end of the film. He has no respect for the army, has defeated his only equal and stands before an army willing to bow at his feet. But he walks away. He refuses to assume power.

What Apocalypse Now explores is the unfathomable concept of control. In truth, people don't have much. But that we see ourselves as having manifests itself through the idea of organisations--countries. Kurtz and Willard alike take journeys towards being able gather the capacity and power to become imperialists--to start their own countries. We never know, but had Kurtz been consumed completely by the control he finds for himself, he could have continued to take over villages, chunks of land, build a bigger and bigger army made up of more competent soldier's that would help him win the war, and, who knows? Take over the country. Kurtz as a dictator could be capable of unthinkable anarchy. But, is that spin off you're dreaming of right now in any way feasible? In any way realistic? Is there any plane of verisimilitude big enough to allow such a thing to happen? This is the question that halts Kurtz's operations, that makes Willard walk away. In short, humanity is that snail and it makes it's trip across the razor blade daily--no sweat. Credit given where credit due, humanity deserves a round of applause. The message Kurtz, that the film, wants to give to the world - Kurtz to his son - is that people can do no better than to be themselves. Kurtz doesn't kill Willard for the hope that he will tell his son his story--no lies, no fabrication. He doesn't believe he is bad, evil, corrupt, but that he's found clarity. And if you can stretch your mind into the realm of postmodernism you could easily agree with him. By seeing authority as nothing more than a figment of our imaginations we can sympathise with Willard's and Kurtz's struggle alike. They face what we daren't - the void. But, with clarity comes the idea that it will all end, not with a bang but a whimper. If you aren't familiar with T.S Eliot's Hollow Men, you can read it here if you like. But to summarise roughly, Eliot sees the heartless and empty men of the world, it's leaders--the faceless and nameless organisations--as inevitably doomed. Eliot's poem is aimed towards the likes of the Kurtz character as presented in Joseph Condrad's Heart Of Darkness (which the film was adapted from) and explains why he's mentioned in the epigraph. Eliot, with the Hollow Men, shows imperialists and those who claim the title of God, to be corrupted and the inevitable cause of the sorry end to humanity if they are allowed to keep their power. Eliot probably sees ultimate power in the hands of God himself (herself? itself?) and so sees imperialism as a form of heresy or blasphemy as one is comparing themself to Him/Her/It.

To offer an alternative explanation in the guise of a film that doesn't rely on religious themes, it seems that any leaders can be considered Hollow Men. The more power you take on, the more hollow, the less human, you become. In short, by seeing yourself as God, by assuming you have control, you dehumanise yourself. Humans, as a species are inevitably going to cease to be one day. The most likely cause to this is through the expense of all our resources and environment. I'm not going to make any specific speculations as to the end of humanity though, merely point out the fact that, by natural law, all species rise, peak and inadvertently kill themselves. Just look at bacteria or yeast cells. If you contain a small population in a sample with a good supply of nutrients, they'll use it, steadily, then rapidly increasing their population. All the while they'll respire, producing CO2 or other toxic byproducts. With population increase comes pollution and ultimately death. Humanity's petri dish is Earth and we could be on that steep slope toward peaking in population and starting to kill ourselves off with our self-pollution. Morbidity slightly to the side, to have control inside this doomed system is to assume responsibility for that end. Whether it's under a country, government, monarchy, dictator, someone's going to have to be the last person to whimper. By transcending authority Kurtz's and Willard see this future and they feel this weight of responsibility. This is why they hit self-destruct. A bang before a whimper, if you'll have it. Apocalypse Now, along with a few other 70s masterpieces really pushed the bounds of cinema in a way that no one has managed since. I know when talking about Adventures In Babysitting I made contradictory statements concerning the power of cinema--and I in no way retract anything I said. But, what I mean here is that Apocalypse Now represents a type of thinking that is not present in the zeitgeist of today. Cinema peaked in the 70s in terms of postmodernism and existentialism and has very quickly immatured. But, that's a talk for another time and another film.

All in all, Apocalypse Now cites the weight of responsibility, the capacity for any man to see himself as God and reject authority, but ultimately shows that to try and rule the world, one must face the self-destruct button. What it communicates is the irrevocable chaos in 'organised' systems, and how if we think things should change, we should first ask ourselves if we could change them. In short, could you, the snail, make it to the end of the razor blade alive?

Thoughts On: Taxi Driver

With a continued look in on 70s classics before looking at Spring Breakers I come now to what could be Scorsese's best film. I started with Apocalypse Now and will be looking at One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest next, with the intentions of exploring the ways in which cinema has changed over the last 40 years, and what the current era of cinema will be defined by. So, Taxi Driver follows an insomniac and a loner, Travis Bickle, through the streets of New York as his disdain for the city and world festers, culminating in an explosive gesture for catharsis and an attempt towards fixing his broken world.

Taxi Driver is the quintessential 'man with a problem' picture. Some like to look down on this kind of film. One of Christopher Nolan's key criticisms is that he tells the same 'man with a problem' stories. From Memento, to The Dark Night, to Inception, his male leads lose the women dear to them and then battle an internal struggle against the loss. Such stories are criticised because women are seen to be objectified, reduced to mere motivation instead of real characters. With 8 1/2 I explore what this is and why it's done. In short, films are dictated by character's perception. But, the main argument against the 'man with a problem' film usually pertains to a question of, why aren't there many 'woman with a problem' pictures? I think this is a genre, or grounds, that cinema hasn't explored too well at all. This may be down to fact that if I were to name a handful of the greatest directors of all time, without prejudice, I wouldn't come up with one woman. Google the 'best directors' and you get Scorsese, Spielberg, Nolan, Fincher, Tarantino, Hitchcock, Ridley Scott, Kubrick, Coppola, Cameron, Eastwood, P.T.A, Woody Allen, Tarkovsky, Rossellini, Goddard, Truffaut, Fellini, Bergman, Ozu, Kurosawa, Lynch, Cronenberg, Bertolucci, Chaplin, Peckinpah, Welles, Leone, Aronofsky, Capra... the list literally goes on and on and on. You don't get a woman until Sophia Coppola, Katheryn Bigelow or Ava DuVernay - and they are way down on the list. This is a very depressing and ultimately confusing reality. I won't pretend that there is one cause to this paradigm, or pretend to know the solution to the problem. But, when looking at Taxi Driver in this respect, you're faced with some difficult questions. Could Travis have been a woman? Yes, of course. But would the film have been as successful? As poignant? I feel the answer is no. The film would have been reduced to an exploitation or 'feminist' picture. Ridley Scott is praised for using characters like Ripley or Thelma and Louise. But, that idea is quite counter productive. Having strong female leads is the equivalent to having 3D in your film. It doesn't instantly make it better, but triggers an audience's interest. I won't delve too deep into these questions here, instead, save it for the talk on Spring Breakers--which I might end up splitting into several parts. What is relevant about the idea of a 'man with a problem' is Travis' issues being universally applicable.

Taxi Driver is about loneliness and authority. Anyone can face such issues, but Travis' retaliation is stereotypically male. The dynamic and tone of this film is reliant on the existence of this idea of a man with a problem and a stereotypical male response. Travis' underlying struggle with loneliness comes with his inability to get along with women and their rejection of him. We can see Travis' fight against societal ostracisation primarily with women, with Betsy and Iris. How Paul Schrader describes the film is as paraphrased: Travis is a guy who wanders around, he can't have the woman he wants and he doesn't want the woman he can have, he then tries to kill the father figure of one and fails, but does manage to kill the father figure of the other and becomes a hero. This is the best thematic summation of the film I've heard--and rightly so, Paul Schrader wrote the film. Travis, as he says, is God's lonely man. But, again using Schrader's view of the film and his intentions, people aren't born lonely, 'we make ourselves lonely'. Those three ideas are the crux of the film. Firstly, there's the problems with women, second is loneliness, third is responsibility. Problem, effect, retaliation. We learn of Travis' problems with direction and of course his narration. Scorsese made a point of directing this film from Travis' point of view, only ever once showing what Travis wouldn't have seen - the scene with Iris and Mathew dancing. We are made to cruise the grimy, grim, ill-lit streets of New York, constantly privy to crime and poverty so that Travis can be further isolated. The blurred and distant lights of the world beyond his cab imply his disconnect and when he opens the door to customers he's letting in more than potential fare. He's relinquishing control and letting in danger. The 'Taxi Driver' is an archetypal character of a person who lives as part of a city. And when that city is dangerous, they are show to be living life on the edge. This is why the archetype is applied to Travis' character. It perfectly captures both his will to be apart of society, but ultimately reduces him to a piece of furniture. This is also Travis making himself lonely. His problems and their effects are looped in positive feedback.

The idea of problems that reaffirm themselves by the actions they induce in us is a very telling paradigm. Almost all of the major issues faced by humanity are manufactured and self-preservative. People decide to go to war, choose to pollute, corrupt, lie, steal. As a whole, humanity is incapable of stepping out of this cycle of causing problems and feeling their burn. Travis' inability to hold onto relationships deepens the commentary. Coming back to women, Travis wants a girl that may be beautiful, but who ultimately isn't much like him and isn't that interested. When he comes across Iris, he comes across a character very similar to himself. She chooses to be a prostitute, to stay with Mathew. She can never step out of the loop. Travis could have easily been with her if he could bypass his own moral sense. But, like almost all of us, he can't - he doesn't sleep with a 12 year old. Women, in this respect, represent Travis' natural urges. But, his morals, standards that are too high and his persona disallows him to adhere to his natural inclinations in a true, or satisfying, sense - yes, he can go to porn theatres, but can't win Betsy over. Why? Because he messes up by taking her, on their first date, to see a porno. He allows himself to destroy what he wants. Porn represents an easy fix. Travis fits into an unfortunate niche here. He's willing to accept the easy fix that isn't good enough (a sticky seat in a porn theatre) whilst refusing another equally easy fix that may be more satisfying - Iris, otherwise known as Easy. Travis' conflict is himself, is this idea of morals. Morals are apart of what makes people human - it's what separates us from the animals. But, humanity is as much a gift as it is a task. Is self-awareness, conscientiousness, are feelings, emotions, really that great? Without them life would be an automated process, not a struggle to balance opposites: love, hate; need, want; society, individuality; us, them. But, the solution to the problems of humanity is not as simple as hitting auto-pilot. Our response to war, corruption, pollution, lies, theft, poverty, inequality, comes in the form of government, democracy, hierarchy, morals, social norm and laws. This idea is expressed though the political elements of this film, but ultimately comes back Travis and women.

Humanity is not perfect despite government, democracy, such and so on. This gives reason as to the state of New York in Taxi Driver and Travis' disdain. Don't worry, I'm not going to go into the historical and political atmosphere of the late 60s and 70s - this is partly because that's a small feature of the film, but mostly because I wouldn't know what I was talking about. With the wold being imperfect, Travis wants change. He sees a failing solution, a lie, in Palantine (the politician) and a worsening and ever prevalent situation around him as expressed through Mathew (the pimp). As Paul Schrader says, to Travis, these are 'father figures'. Travis isn't at all concerned with politics, but the girl at the politician's head quarters. Travis isn't so much concerned with the combatance of drug and gang crimes, neither prostitution. He simply wants a rain of biblical proportions to wash them all away, flush them down the toilet. His reasons for engaging in the final conflict are selfish, just as the reason why he didn't assassinate Palantine was. By killing Palantine, Travis wouldn't have won, spited, or helped Betsy. And so, he was quick to give up on the pursuit of what can be considered an authority figure above her. Killing Mathew and the organisation around the pimp is the only way Iris could escape her cycle. But, she's 12, Travis has no sexual inclination to save her. Travis, as a loner, may only break the cycle of his own pain by ending his life with the alleviating idea being that he died for a good reason - saving Iris. In short, in self-pity, Travis decides to affect the world the only way he knows how. There's a little more to the ending of the film though. The reasoning behind all the destruction comes with an idea of retaliation to authority. Travis makes himself lonely by telling himself the world is disgusting, that there is no solution to its problems beyond washing it all away and starting again. The final conflict is not representative of Travis washing away the problems of the world, but his problems with the world. He allows himself to see Mathew as the symbol of all that is wrong in his city. When he destroys that symbol, he's rewarded, but is ultimately left the same person. Travis has metaphorically washed out the streets of New York and in the end of the film, with him coming across Betsy again, he's reminded that he's merely displaced its issues - just like he has his own.

This idea links to Travis helping the girl he does not want. Here's the sad reality of the film. Travis was in the papers, Iris is safe, but all will probably be forgotten, Iris will probably hate school and would have only adopted a whole new set of problems. How easy would it be for a 12 year old former prostitute to fit in with other girls? Her problems, like his problems, have been displaced, not solved. The true happy ending to the film would have been some wishy-washy transformation which allowed Travis to get Betsy. But, hold on, that's not exactly true. How well do you think their marriage would go? Not very well at all. Travis was doomed from the beginning. He is the type of man that will probably forever be stuck in a cycle of his own issues. This is why Scorsese made the film. He thought it was a form of maturity, that it was ok to have the feelings of hatred Travis had, but not to cross the line he did. Taxi Driver asserts that some times it's not the world that needs to change, but your view of it - and that you can't go killing the fathers of the women you like because they represent a wall. It's Palantine that represents democracy and a sense of control in Betsy that Travis (as a person who ultimately devolves into an anarchist) can't get along with. It's Mathew as an immoral dreg of society that represents why Travis can't have Iris. In short, to be with those women he must be like them, be like their father figures. It's Travis' isolation from society, from other men, that makes him incapable to behaving like them. That is why this is a 'man with a problem' picture. It centres around the world of men with themes of not belonging. It's because Travis isn't the stereotypical man that he can't get the women he wants. By adapting the downfalls of the stereotypical man however (aggression, violence) Travis only recycles his descent--furthering himself from the idea of an average man and getting the women he desires. This speaks to the film's bigger picture which deals with the conflicts of humanity. In the same way Travis dooms himself, we shouldn't want to 'fix' the problems with humanity. We shouldn't be looking for the auto-pilot button. Problems must be dealt with internally, not externally. War? Everyone decides they don't want to kill or be killed and it won't happen. Pollution? Everyone decides they care about the future of our environment and they wont' actively harm it. The same goes for any and all major issues humans have made for themselves. But, alas, the major issue is humanity and me asking everyone to change, too look inside themselves, is just as futile as shooting up a crack den--no matter how good it makes me feel or how others praise me.

All in all, Taxi Driver is about responsibility. It's about taking your issues and dealing with them internally, not trying to project them onto the world around you and then asking or forcing it to change. The person that you should be asking 'you talking to me?' is not any figure of authority, of power, of opposition. No, you save the question for the mirror and maybe one day your refection will talk back, they might say 'yes, let's having a conversation'. Whether you shoot at them or not is up to you, but remember, the gun's not loaded.

Thoughts On: One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest

The last 70s classic I'll be looking at before diving into Spring Breakers. This follows Randle McMurphy into a mental institution, where he discovers the life of a psychiatric patient isn't so mellow and free.

This movie, despite the end, is one of the most joyous films of all time. It does this by perfectly balancing the idea of chaos with control and restraint through mischief. Jack Nicholson perfectly captures a person with little restraint, little self-control, but an abundance of respect and heart. It's because Randle only wants to enjoy himself that he can rouse a sense of humanity and normalcy in those others would consider insane. In short, Randle only wants to see the likes of himself in others and so can see character beyond facade. This is ultimately how we see and is what makes this film absolutely phenomenal. Whilst the film does have themes and questions surrounding a question of normality versus insanity, I won't be focusing on them today. What we'll be looking at is is the two core ideas of the film. The first is chaos and disorder for the sake of levity or fun. The second is trapping yourself and being trapped. Let's jump right into what Randle represents. He is the part of you that picks up snowballs even though you know you're hands are going to get cold, wet and probably to the point where you're almost in tears. Randle is what makes you put glue or sticky tape in your friend's hair for a laugh. You've ruined their day, possibly the next month of their life, but, shit it was funny. Impulsiveness and good intent laced with apparent malice, this is Randle. I mean, just look at that smile up there... I need say no more. How he explains himself as the chaos factor to an organising body (the psychiatric hospital) is that he fights and fucks too much. He is, for all of those who've taken a psychology class, representative of the id - instinctively drawn to innate impulses. Law's purpose is to essentially control that part of society. But, with ease, Randle can have Dr. Spivey smiling over the idea of statutory rape and the audience cured of any disillusion. This has quite a bit to do with antiheroes, but Randle's case is quite special. Sex driven teens are quite the norm, as are gangsters, murderers, monsters and idiots. All common antiheroes. What Randle manages to be is an amalgamation of Travis Bickle and Alex DeLarge. This comes back to what makes the film special. Randle is the dark antihero, your Batmans, Charles Foster Kanes, Jim Starks, or Men With No Names. At the same time he's a Patrick Bateman, Juels Winnfield, Joker, Sugar Kane Cowalczyk, Jordan Belfort. There's a very strong sense of of both ying and yang in his character that few others can manage.

Whereas The Joker can get away with beign 90% bad but 10% truly entertaining, Randle splits the divide evenly because One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest ultimately isn't about bad trumping good. This film is made up of antiheroes and the naive. Nurse Ratched may seem like an antagonist, but with an antihero in a realist picture, she can't be the bad guy, but a representative of Randle's opposite. She may act in opposition to him, but not in hostile way, and so, she's not a true antagonist. This will eventually link into trapping oneself and being trapped, but the first takeaway here is that of balance. When we take into consideration all sides of character motivation, the film asks how much control an institution should have. This is best summed up with the cigarettes ordeal. All patients have their cigarettes rationed and doors locked because they essentially aren't trusted to look after themselves. Because Randle won all their smokes, Nurse Ratched decides to look out for her patients and stop what she assumes to be cheating from happening--just like countries may make gambling illegal. But, as Manchini says, how, without their cigarettes, will they win any back? To control we must minimize risk. But risk, the whole concept of odds and imbalance, is meant to excite a system, both in an emotional and physical sense. The freedoms of being an adult are best utilised by those trying to do something childish and stupid. Mistakes are seen as a right to an individual, but on a larger scale, mistakes are big no, nos. Randle is chaos, Nurse Ratched is control and we are the likes of Martini, Taber and Cheswick. We are the impressionable. I like to say this too much, but, the crowd is the stupidest person of all. They can be lulled into routine or sparked into chaos like a child with ice cream; refuse to give it to them, they scream, give it to them, they love you, they drop it, they scream again, give them another, they're grinning again. This kind of makes Randle the big kid who'd happily smack the ice cream out of your hand and Ratched the parent who warned you not to drop it. But, ice-cream and tears are trivial matters. What the film is more concerned with is the over-reactions, the misunderstandings. In the same way Taber shouldn't have been detained because a cigarette burnt his foot, Nurse Ratched didn't deserve to be strangled. At the same time, I don't think Randle really needed lobotomising either. But, the question raised is, who would? Are the over-reactions always unjust?

The conflict between control and chaos in a liberal or moral society--liberal more so--is tantamount to embarrassment. With rules such as freedom of speech, people are forced into a corner when they hear something they do't want to. People and idealism don't work together because people hate contradiction, but love to say we're all human. The cycle is quite funny to me. As a species humans yearn for paradigms - formulas that make us all happy. But, one of the worst attempts at this is the idea of doing onto others as you'd want done onto yourself. Equality is one of the key ideals of our day and age, the idea is prospectively warming, but when faced at present isn't always so fun. Equality is sharing your toys with that snot nose kid that got away with making you eat sand. Equality is staring the nurse who just drove your friend to suicide in the eye and saying, well, I'm sure you didn't mean for that to happen. Equality is blind tolerance, blind forgiveness. Why should we love our enemies? Yes, I can pragmatically say that Nurse Ratched didn't deserve to be strangled, but had I stood in Randle's shoes, like almost all of us, I could have strangled the bitch. Maybe I wouldn't, but I could not forgive her so easily. This is the embarrassing state of conjecture. We love to ignore apparent truths or what makes us look bad so we can get those retweets, that round of applause from strangers. Here's one I love, 'treat your girl like a queen and you become a king'. I see it all the time, but, no, simply, no. All that sounds like to me is an abusive relationship. But, it keeps the girls smiling and the guys' hopes of sticking it in you high--so, shh. From a literal perspective, people love to spew nonsense and this translates to the film's ideas through its main conflict. Both Randle and Nurse Ratched are trying to look out for the patients at the psychiatric hospital. Randle, for fun. Nurse Ratched, because it's her job. Both for moral comfort in helping others. The patients maybe need parties and alcohol as much as they do therapy and pills. Both sides of the spectrum (Randle/Ratched) don't want to accept this. The true tragedy in the end of this film is not that Randle is reduced to a zombie, but that the film had to end, that things got so out of hand. The reasons for this link to the second idea of the movie.