Inception - Lessons vs. Stories: Why Exposition (Sometimes) Sucks

Thoughts On: Inception (2010)

This is a film we've covered before, link here, but will be looking at in a new light.

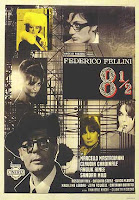

Inception is a significant film for quite a few reasons. Primarily, however, Inception is a huge big-budget blockbuster that had the courage to be quite complex and multi-faceted. And despite this, Inception was a significant success and already is considered one of the greatest films ever made. What adds to this significance is this meeting of the success, the blockbuster and the complexity. There are dozens of films that I could name that are more complex than Inception, and quite a few of them would be considered all-time greats - consider for example Persona, 8 1/2, Last Year At Marienbad, Blow-Up, The Seashell And The Clergyman, 2001: A Space Odyssey or Meshes Of The Afternoon. However, whilst many of these films are more complex and profound than Inception, Nolan's film manages to transcend the line between the cinephile and the average movie goer - something that very few movies manage to do whilst being starkly challenging.

For this, it is nearly impossible not to respect Christopher Nolan. However, if you've been reading Thoughts On posts for a while, you'll probably know that, whilst I respect Nolan, I don't admire him to a degree that is so high. There are quite a few reasons for this and the first was inadvertently explored with an early post on Human Cinema.

"Human Cinema" is a phenomena you see across almost all films, but is particularly noticeable now that we are in the modern digital age. In short, when we look to films such as The Avengers, Transformers or Batman, we see films that we're told are all about huge alien robots, gods, superheros, supervillians and vigilantes. However, the confounding paradox that arises in high-end fantasy digital cinema is one centred on realism. Not only do filmmakers shy away from fantasy for the sake of reality (realism), but they often focus their narratives on the normal - which often translates to relatively boring, average people. This philosophy obviously comes from the idea that people want to see/learn about themselves through cinema. However, for this to directly translate into us having to sit through movies centred on Bruce Wayne rather than Batman, Sam Witwicky instead of Optimus Prime or a plethora of sub-characters in the form of government agencies, the police, the army or the average citizen in place of the marketed protagonists and the only real reason we came to see this movie, is kind of absurd.

We could delve deeper into the phenomena of Human Cinema, but suffice to say that Nolan employs this in many of his films - the Dark Knight trilogy being a perfect case. However, layered onto this are two more key problems. The first is the projection of fantasy and the second is a plain old vanilla problem.

Starting with the latter, almost all of Nolan's films have great concepts within them - a film like Inception is a brilliant case study for this. As we covered in arduous and infuriating detail in the previous post on Inception, there's a lot lacking in Nolan's projection of 'the dream'. In the simplest terms, Inception lacks the surrealism and the fantasy inherent to a very similar film, Paprika. Again, without delving too deeply into this, Nolan simply betrays an idea of sci-fi and fantasy in focusing on plot as opposed to story and the world in which it exists through films like Inception. When we add to this the latter problem, that being the "Vanilla Problem", we see this betrayal of fantasy for realism begin to pervade not just Nolan's script, but also his direction and thematic projection through film language. When looking at a film such as The Dark Knight, we see this overwhelmingly. Not only is the focus of the story too human-centric, but there is also too much of a focus on plot - added to this, the manner in which Nolan captures this all with direction is very bland.

So, when I look to Nolan's body of work, I see something lacking in many ways. I'll repeat again that I think Nolan is a significant filmmaker that, especially in 2010, shows (showed) the world that cinema, even at its highest ends, can be more complex and challenging. But, there is another key aspect of Nolan's cinema that I think reduces his significance and stature. Before we delve into this, I don't write these critical essays to just say that Nolan or a certain filmmaker is bad or lacking. I think if we reflect on the figures of modern cinema, assessing their strengths and weaknesses, we can both learn from them and learn how to design our own idea of cinema that they may fail in capturing. And with that said, we'll continue...

An intriguing element of Inception is that this is a story centred, almost entirely, on exposition. If you question the motive of every line of dialogue, you will find that an overwhelming majority of it explains, directly to an audience, something that is happening or has happened. There are then two main motives of all of the dialogue in Inception; 1) It explains the movement of the plot and the concept of the film - everything to do with dream machines and levels of dream spaces, or, 2) It explains Cobb's backstory and his inner conflicts.

This in itself would seem really bad to most movie goers as exposition is often seen as a necessary evil that should be kept to an absolute minimum. I agree with this idea, but I don't entirely subscribe to it. Exposition, whilst it can treat your audience like a bit of an idiot, is an amazing tool for world building. We can then grow to see exposition as both a good and an evil - not just a necessary evil. Good exposition is then a medium through which you can tell an audience something that imagery either could not, or if it did, would not be as engaging or fun as it being told from a character's mouth through dialogue. Some of the greatest uses of exposition can then be seen through films such as Fight Club and Ferris Bueller's Day Off.

In Fight Club, we are constantly being told information that is somewhat tangential to the plot, or information that characterises certain figures - for example Tyler and The Narrator are characterised by their constant monologues explaining their philosophies and predicaments.

In Ferris Bueller's Day Off, we are also given information, especially in the first act, that is tangential to the plot, but nonetheless interesting and a means of better getting to know Ferris.

What both of these film begin to show is that good exposition is fun exposition - it builds worlds and characters. Through Inception, we see a use of exposition that probably is more densely packed than even Fight Club, and whilst it builds a world and explains the plot as it moves, it doesn't do very well in characterising Cobb or injecting some fun into the narrative.

It is this scene, in which Cobb explains how dream machines and architecture works, that is the most awe-inspiring aspect of the movie on a surface level and in terms of its exposition. This is because, as in Ferris Bueller and Fight Club, it gives the audience information that enriches the story, instead of exposition that merely moves the plot along. But, what happens as the plot progresses is that this scene is forgotten; it turns out that it only explained Ariadne's role and wasn't there to foreshadow something in the second or third act. This great scene was then a simple block of information, little more. It is exposition like this that is a means to an end that is 'the evil' of storytelling. To understand this, we'll have to delve into the problem that lies at the heart of this topic.

When we ask ourselves why we want to tell and be told stories, we can often come to the conclusion that we want to learn something new or experience something different. Because of this, we can go to movies looking for one of two things; for an entertaining experience or an intellectual one. Because we are discussing complex movies through Inception, we are going to focus on the intellectual experiences we may seek out. In such, we come to a realm of filmmaking that, through metaphors or direct exposition, means to teach us something about, or connected to, the human condition. This is what we find through the films mentioned when referencing movies that are more complex than Inception...

However, would the likes of Kubrick, Fellini, Deren and Bergman consider themselves lecturers and teachers? It is possible, but what supersedes this idea is almost certainly that they are storytellers and artists. Hence, we have a line drawn in the sand that separates lessons from stories. So, when we consider ideas of meaning and exposition in cinema, we come to a conundrum. What is the motivation of meaning and exposition if it is not to teach?

The answer to this question can be teased out when we break down the idea of a 'lesson'. There are some lessons that we can all go to school for; we'll learn about history, science and mathematics. Other lessons cannot really be taught in the classroom; lessons pertaining to art and philosophy. This can be considered to be true in all disciplines, but it takes an individual endeavour, voice and exploration to progress in philosophical thinking and artistic practices. As implied, the same may be said in the highest forms of science and mathematics - consider the creativity and individual endeavour of figures such a Einstein. However, whilst you can be guided and taught by others to a certain degree in the disciplines of storytelling and thinking, there are elements that simply cannot be taught, only learnt through experience.

Because of this, there is a paradigm that splits sciences and arts apart. Science can be learned quantitatively, with facts and figures, whilst art can be practised with a degree of facts, figures and rules, but has often to be executed with the use of personality and subjective perspective. In turn, science can be consumed and taught in a quantitative manner - one based in facts and rules - whilst art has to be consumed and taught with ambiguity - no real lessons, just implication, symbolism and metaphors. What we are then seeing with art is the means through which it is 'learnt' mimicking the means through which it is consumed. In such, the real lessons in how to create art are gained through experience and practice and so the 'lessons' that art means to teach must be given in the same manner - with reliance on an audience who will use their own individual experiences and practices to interpret a narrative.

When we consider such an idea and turn back to our assessment of meaning and exposition, we see that the tools of storytelling that give it direction and purpose should not aim to teach a lesson in a scientific or mathematic manner, but imply a 'story', a narrative of experience, through which personal interpretations can be drawn. What this then means is that stories are not lessons; stories instead mimic, to a certain degree, the lives we live and gain experiences from; lives that inadvertently or indirectly teach us lessons. When we look to Inception, we see themes of family meeting ideas of control, the unconscious and the dream, which has the potential to provide a great narrative through which we can experience and learn something about the human condition. However, Inception is not a very profound film as it does not handle its themes and subject matter very well.

The reason why this is comes down to the fact that Nolan's exposition builds a world, but does not put us in it very well so that we can experience and draw our own meaning. A story like Fight Club does the opposite; the exposition is not only fun and interesting, but it builds worlds and characters that hold inherent lessons and ideas to be explored within them. This is good exposition. Bad exposition misconstrues storytelling as a platform through which to teach direct, pseudo-scientific or mathematic lessons - and this is exactly why exposition often sucks. Good exposition is another form of storytelling that implies indirect and ambiguous lessons whilst bad exposition is a misplaced lecture.

The final idea I then want to touch on before moving towards conclusion is how bad movies with good intentions are constructed. To explore this, we'll actually start with a T.V show. I happened to catch about 10 minutes of Orange Is The New Black recently.

I've never seen this show before and was simply in the room when somebody put it on the T.V, which means my opinion on the show isn't an incredibly valid one, but those 10 minutes that I saw were horribly written. I have no idea about the episode number or season, but what characterised every moment of what I saw was blatant political exposition with reference to a lot of leftist, female-centric ideas - everything from long dicks to girthy dicks to shaving to the patriarchy and social dominance hierarchies to sexual identity to culture, language, ethnicity, maternity... it goes on. Some of these are compelling and intriguing themes or topics, but the manner in which they were written into the show was awful - and the reason why I stay away from T.V shows in general. Everything about the dialogue and plot all came from a writer, or writers, trying to teach a social studies class to the world under the guise of a story. Their intentions may have been good, but the product was dog shit.

We see this paradigm in bad movies too. Examples of this would come from films like the recent Batman V Superman; the politics and the thematic intentions were transparent, unprofound and terribly implemented into the movie. This was all because, like in those 10 minutes of Orange Is The New Black, there was no sense of cinematic storytelling and no ambiguity; the story did not construct a narrative and a world which we, almost independently and with slight guides by the writer, step into and learn about ourselves through. Again, we have this in Inception too. Nolan is too focused on expositing a backstory and a concept that there is never the time nor means for the audience, and even the writer, to actually explore what their significance is.

So, to conclude, stories are constructed worlds captured by cameras and put into a screen. The best stories, like the most important and profound of our experiences on this earth, are narratives we walk through and draw lessons from. The world provides no real exposition; we can be told tangential facts that make the journey through life more interesting, but it is experience and action that truly matter - the same must be true in cinema. Inception is ultimately a sparkling example of how this complex and important side of cinema can be approach, but not entirely reached.

So, to end, I turn to you. What are your thoughts on all we've covered as well as Inception itself?

Previous post:

End Of The Week Shorts #10

Next post:

I Won't Come Back - When Home Calls

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

This is a film we've covered before, link here, but will be looking at in a new light.

Inception is a significant film for quite a few reasons. Primarily, however, Inception is a huge big-budget blockbuster that had the courage to be quite complex and multi-faceted. And despite this, Inception was a significant success and already is considered one of the greatest films ever made. What adds to this significance is this meeting of the success, the blockbuster and the complexity. There are dozens of films that I could name that are more complex than Inception, and quite a few of them would be considered all-time greats - consider for example Persona, 8 1/2, Last Year At Marienbad, Blow-Up, The Seashell And The Clergyman, 2001: A Space Odyssey or Meshes Of The Afternoon. However, whilst many of these films are more complex and profound than Inception, Nolan's film manages to transcend the line between the cinephile and the average movie goer - something that very few movies manage to do whilst being starkly challenging.

For this, it is nearly impossible not to respect Christopher Nolan. However, if you've been reading Thoughts On posts for a while, you'll probably know that, whilst I respect Nolan, I don't admire him to a degree that is so high. There are quite a few reasons for this and the first was inadvertently explored with an early post on Human Cinema.

"Human Cinema" is a phenomena you see across almost all films, but is particularly noticeable now that we are in the modern digital age. In short, when we look to films such as The Avengers, Transformers or Batman, we see films that we're told are all about huge alien robots, gods, superheros, supervillians and vigilantes. However, the confounding paradox that arises in high-end fantasy digital cinema is one centred on realism. Not only do filmmakers shy away from fantasy for the sake of reality (realism), but they often focus their narratives on the normal - which often translates to relatively boring, average people. This philosophy obviously comes from the idea that people want to see/learn about themselves through cinema. However, for this to directly translate into us having to sit through movies centred on Bruce Wayne rather than Batman, Sam Witwicky instead of Optimus Prime or a plethora of sub-characters in the form of government agencies, the police, the army or the average citizen in place of the marketed protagonists and the only real reason we came to see this movie, is kind of absurd.

We could delve deeper into the phenomena of Human Cinema, but suffice to say that Nolan employs this in many of his films - the Dark Knight trilogy being a perfect case. However, layered onto this are two more key problems. The first is the projection of fantasy and the second is a plain old vanilla problem.

Starting with the latter, almost all of Nolan's films have great concepts within them - a film like Inception is a brilliant case study for this. As we covered in arduous and infuriating detail in the previous post on Inception, there's a lot lacking in Nolan's projection of 'the dream'. In the simplest terms, Inception lacks the surrealism and the fantasy inherent to a very similar film, Paprika. Again, without delving too deeply into this, Nolan simply betrays an idea of sci-fi and fantasy in focusing on plot as opposed to story and the world in which it exists through films like Inception. When we add to this the latter problem, that being the "Vanilla Problem", we see this betrayal of fantasy for realism begin to pervade not just Nolan's script, but also his direction and thematic projection through film language. When looking at a film such as The Dark Knight, we see this overwhelmingly. Not only is the focus of the story too human-centric, but there is also too much of a focus on plot - added to this, the manner in which Nolan captures this all with direction is very bland.

So, when I look to Nolan's body of work, I see something lacking in many ways. I'll repeat again that I think Nolan is a significant filmmaker that, especially in 2010, shows (showed) the world that cinema, even at its highest ends, can be more complex and challenging. But, there is another key aspect of Nolan's cinema that I think reduces his significance and stature. Before we delve into this, I don't write these critical essays to just say that Nolan or a certain filmmaker is bad or lacking. I think if we reflect on the figures of modern cinema, assessing their strengths and weaknesses, we can both learn from them and learn how to design our own idea of cinema that they may fail in capturing. And with that said, we'll continue...

An intriguing element of Inception is that this is a story centred, almost entirely, on exposition. If you question the motive of every line of dialogue, you will find that an overwhelming majority of it explains, directly to an audience, something that is happening or has happened. There are then two main motives of all of the dialogue in Inception; 1) It explains the movement of the plot and the concept of the film - everything to do with dream machines and levels of dream spaces, or, 2) It explains Cobb's backstory and his inner conflicts.

This in itself would seem really bad to most movie goers as exposition is often seen as a necessary evil that should be kept to an absolute minimum. I agree with this idea, but I don't entirely subscribe to it. Exposition, whilst it can treat your audience like a bit of an idiot, is an amazing tool for world building. We can then grow to see exposition as both a good and an evil - not just a necessary evil. Good exposition is then a medium through which you can tell an audience something that imagery either could not, or if it did, would not be as engaging or fun as it being told from a character's mouth through dialogue. Some of the greatest uses of exposition can then be seen through films such as Fight Club and Ferris Bueller's Day Off.

In Fight Club, we are constantly being told information that is somewhat tangential to the plot, or information that characterises certain figures - for example Tyler and The Narrator are characterised by their constant monologues explaining their philosophies and predicaments.

In Ferris Bueller's Day Off, we are also given information, especially in the first act, that is tangential to the plot, but nonetheless interesting and a means of better getting to know Ferris.

What both of these film begin to show is that good exposition is fun exposition - it builds worlds and characters. Through Inception, we see a use of exposition that probably is more densely packed than even Fight Club, and whilst it builds a world and explains the plot as it moves, it doesn't do very well in characterising Cobb or injecting some fun into the narrative.

It is this scene, in which Cobb explains how dream machines and architecture works, that is the most awe-inspiring aspect of the movie on a surface level and in terms of its exposition. This is because, as in Ferris Bueller and Fight Club, it gives the audience information that enriches the story, instead of exposition that merely moves the plot along. But, what happens as the plot progresses is that this scene is forgotten; it turns out that it only explained Ariadne's role and wasn't there to foreshadow something in the second or third act. This great scene was then a simple block of information, little more. It is exposition like this that is a means to an end that is 'the evil' of storytelling. To understand this, we'll have to delve into the problem that lies at the heart of this topic.

When we ask ourselves why we want to tell and be told stories, we can often come to the conclusion that we want to learn something new or experience something different. Because of this, we can go to movies looking for one of two things; for an entertaining experience or an intellectual one. Because we are discussing complex movies through Inception, we are going to focus on the intellectual experiences we may seek out. In such, we come to a realm of filmmaking that, through metaphors or direct exposition, means to teach us something about, or connected to, the human condition. This is what we find through the films mentioned when referencing movies that are more complex than Inception...

However, would the likes of Kubrick, Fellini, Deren and Bergman consider themselves lecturers and teachers? It is possible, but what supersedes this idea is almost certainly that they are storytellers and artists. Hence, we have a line drawn in the sand that separates lessons from stories. So, when we consider ideas of meaning and exposition in cinema, we come to a conundrum. What is the motivation of meaning and exposition if it is not to teach?

The answer to this question can be teased out when we break down the idea of a 'lesson'. There are some lessons that we can all go to school for; we'll learn about history, science and mathematics. Other lessons cannot really be taught in the classroom; lessons pertaining to art and philosophy. This can be considered to be true in all disciplines, but it takes an individual endeavour, voice and exploration to progress in philosophical thinking and artistic practices. As implied, the same may be said in the highest forms of science and mathematics - consider the creativity and individual endeavour of figures such a Einstein. However, whilst you can be guided and taught by others to a certain degree in the disciplines of storytelling and thinking, there are elements that simply cannot be taught, only learnt through experience.

Because of this, there is a paradigm that splits sciences and arts apart. Science can be learned quantitatively, with facts and figures, whilst art can be practised with a degree of facts, figures and rules, but has often to be executed with the use of personality and subjective perspective. In turn, science can be consumed and taught in a quantitative manner - one based in facts and rules - whilst art has to be consumed and taught with ambiguity - no real lessons, just implication, symbolism and metaphors. What we are then seeing with art is the means through which it is 'learnt' mimicking the means through which it is consumed. In such, the real lessons in how to create art are gained through experience and practice and so the 'lessons' that art means to teach must be given in the same manner - with reliance on an audience who will use their own individual experiences and practices to interpret a narrative.

When we consider such an idea and turn back to our assessment of meaning and exposition, we see that the tools of storytelling that give it direction and purpose should not aim to teach a lesson in a scientific or mathematic manner, but imply a 'story', a narrative of experience, through which personal interpretations can be drawn. What this then means is that stories are not lessons; stories instead mimic, to a certain degree, the lives we live and gain experiences from; lives that inadvertently or indirectly teach us lessons. When we look to Inception, we see themes of family meeting ideas of control, the unconscious and the dream, which has the potential to provide a great narrative through which we can experience and learn something about the human condition. However, Inception is not a very profound film as it does not handle its themes and subject matter very well.

The reason why this is comes down to the fact that Nolan's exposition builds a world, but does not put us in it very well so that we can experience and draw our own meaning. A story like Fight Club does the opposite; the exposition is not only fun and interesting, but it builds worlds and characters that hold inherent lessons and ideas to be explored within them. This is good exposition. Bad exposition misconstrues storytelling as a platform through which to teach direct, pseudo-scientific or mathematic lessons - and this is exactly why exposition often sucks. Good exposition is another form of storytelling that implies indirect and ambiguous lessons whilst bad exposition is a misplaced lecture.

The final idea I then want to touch on before moving towards conclusion is how bad movies with good intentions are constructed. To explore this, we'll actually start with a T.V show. I happened to catch about 10 minutes of Orange Is The New Black recently.

I've never seen this show before and was simply in the room when somebody put it on the T.V, which means my opinion on the show isn't an incredibly valid one, but those 10 minutes that I saw were horribly written. I have no idea about the episode number or season, but what characterised every moment of what I saw was blatant political exposition with reference to a lot of leftist, female-centric ideas - everything from long dicks to girthy dicks to shaving to the patriarchy and social dominance hierarchies to sexual identity to culture, language, ethnicity, maternity... it goes on. Some of these are compelling and intriguing themes or topics, but the manner in which they were written into the show was awful - and the reason why I stay away from T.V shows in general. Everything about the dialogue and plot all came from a writer, or writers, trying to teach a social studies class to the world under the guise of a story. Their intentions may have been good, but the product was dog shit.

We see this paradigm in bad movies too. Examples of this would come from films like the recent Batman V Superman; the politics and the thematic intentions were transparent, unprofound and terribly implemented into the movie. This was all because, like in those 10 minutes of Orange Is The New Black, there was no sense of cinematic storytelling and no ambiguity; the story did not construct a narrative and a world which we, almost independently and with slight guides by the writer, step into and learn about ourselves through. Again, we have this in Inception too. Nolan is too focused on expositing a backstory and a concept that there is never the time nor means for the audience, and even the writer, to actually explore what their significance is.

So, to conclude, stories are constructed worlds captured by cameras and put into a screen. The best stories, like the most important and profound of our experiences on this earth, are narratives we walk through and draw lessons from. The world provides no real exposition; we can be told tangential facts that make the journey through life more interesting, but it is experience and action that truly matter - the same must be true in cinema. Inception is ultimately a sparkling example of how this complex and important side of cinema can be approach, but not entirely reached.

So, to end, I turn to you. What are your thoughts on all we've covered as well as Inception itself?

Previous post:

End Of The Week Shorts #10

Next post:

I Won't Come Back - When Home Calls

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack