Moana - Syzygetic Projection & Gaze

Thoughts On: Moana (2016)

This post does not engage Moana directly, but uses it to analyse the ways of approaching narratives as embodiments of yin and yang.

The fidget spinner. I have recently been immersing myself in a lot of Jung. In fact, for quite a while now I have been coming to terms with some of his key ideas (anima, animus, Logos and Eros in particular) and listening to chapters of Aion. More recently, however, I have started working my way through The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. And in conjuncture with this, my thoughts have wandered towards the fidget spinner.

The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious is a volume of Jung's essays that seems to define him in his most abstract and, to me, fascinating lights. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious deals with the human psyche as caught between biological and Freudian psychology. Whilst biological psychology considers all to do with the psyche in regards to the material body as it has evolved over hundreds of thousands and millions of years, and whilst Freudian psychology deals with the psyche as a product of, primarily, childhood, Jung deals with the psyche as reflective of mythological tropes that are thousands of years old and in regards to the individual's interaction with them from a young age. Jung then investigates the psyche and essential humanity as something given and, to a degree, taken. He refers to his key theoretical entities, the archetypes, as equivalent to Plato's Ideas. There are thousands of words that could be written about that sentence alone, but, one key concept that I want to highlight is that, in alluding to the Platonic 'Idea', Jung is alluding to the products of conscious being - thoughts of, exploring and defining form; ideas - as gifts given. One does not make an idea. An idea, when it is beyond mere opinion, when it is a fact reflective of reality, is accepted from a realm transcendent of ourselves. This indeed sounds highly metaphysical, but Jung emphasises that such an idea is far from this. Jung's archetypes are Ideas as images: imagos. The imago is the picture we create of someone, and it is often not a completely realistic one as it lends itself to bias, exaggeration and idealisation. Nonetheless, the imago as 'Idea as image' and 'archetype' is not constructed singularly by an individual. Like ideas are considered by Plato as gifts from the abstract, stars plucked out of the heavens, archetypes emerge from the collective unconscious in accordance to Jung. And the collective unconscious, a relatively simple idea, is a conceptualisation of all shared human thoughts and traits; the collective unconscious is made up of everything that, to a good degree, is in all people. It is all the unconscious thoughts and predispositions we share.

The archetype as a product of the collective unconscious is what necessitates a study of mythology, fairy tale and religion for Jung, for these are collections of unconscious imagos, characters and narratives that form a library and history of human thought. Whilst mythology is not the birthing point of archetypes, they reflect the most fundamental Ideas that humans, conscious or not, gleaned from the universe. As a result, to understand Jung's archetypes, especially the anima and animus, which are arguably the most important archetypes, one must start with a conceptualisation of the universe. Ironically, we will have to conceptualise of the universe in terms of ourselves, in reference to mythology and Ideas of the collective unconscious. This, however, will make clear why Jung is so insistent upon the personal unconscious as intrinsically bound to the collective unconscious.

We would all be very familiar with this symbol. This is the simplified representation of the taijitu. It emerges from Chinese philosophy and Taoism and is a mandala. In such, it represents the universe. The universe, the circle, is made up of a duality; negative and positive. However, in the negative and the positive are attributes of the antithesis, implying that positive can come from negative, that negative can come from positive and that the two are only in balance when such is the case. The negative and the positive are abstract, non-concrete ideas. In such, they can be seen to represent dark and light, passive and active, male and female, etc.

In the realm of the taijitu, and, indeed, in the realm of Jung, too, it seems that masculine and feminine pre-exist the human man and woman. And this is a profoundly important element of Jungian archetypal theory. Men imitate the 'masculine' side of the universe whilst women imitate the 'feminine' side of the universe. Jung is wary about defining what masculine and feminine mean in these regards, but, with anima and animus, he alludes to the 'soul' (anima; female) and 'heart' (animus, male). In alluding to this, he immediately emphasises that he does not want to invoke dogmatic conceptions of either male or female, rather, only wants to enter a realm in which we intuit what is masculine and what is female, not just in regards to our culture and society, but in regards to the conception of the universe we inherit from the collective unconscious. Jung, in this sense, does not believe that male and female are merely social constructs; they reach deep into human history and, quite essentially, transcend it. Furthermore, Jung believes that the collective unconscious has understood, and so represents, truth.

Archetypes are the manifestation of truth. However, they are not pure. Archetypes are mapped onto the world, they are imagos, and thus they become social constructs to a degree. Moreover, they can become pathologised; made receptacles for all of our complexes. The anima and animus are then not yin and yang; they are our idea of the ultimate female and male, and, in turn, they are idols of yin and yang held in our psyche. In turn, they can be corrupted if we do not monitor and work with them consciously. Alas, let's take a step back. Fidget spinners.

What I want to take you through is a thought experiment that questions what the fidget spinner may symbolise if it, itself, is interpreted as a mandala. To start the thought experiment, we should recognise that the fidget spinner was designed to capture the attention of people (children and young people) who fidget. There were claims that it could help people with ADHD and autism, but these claims are not scientifically supported.

I think it would be fair to say that, in complete ignorance of the toy's purpose, the fidget spinner became a huge fad product. I think it has gone away by now. There are multiple videos online of people using pressurised air to make them spin ridiculously fast and, in addition to this, people have set them on fire and turned them into weapons - and then, I'm sure, made them spin at thousands of rotations per second. This would indicate that the toy has ran its due course. Alas, why did it become so popular?

Most simply, the toy is mildly captivating and a physical novelty; it spins at a faster rate that you'd think having not spun one and so the sensation of it spinning on your finger is fascinating. If we were to delve a little deeper, however, we could look at the design of the spinner.

What we have here is a central button, a ball bearing, surrounded by three weighted lobes. The lack of friction surrounding the central button and the balanced weight of the three outer lobes allows for smooth spinning. Moreover, the three holes make for an optical illusion as they spin. What is fascinating about this design here is the use of 3. Fidget spinners will work well with a various number of lobes; common designs range from 2-6. However, 3 is the primary design. This has much to do with size requirements and the device fitting in small hands. But, could we make a stretch and - just for the sake of analysis - question the three lobes as a symbolic reference.

3 and multiples of 3, 12 in particular, are numbers that people seem quite drawn to - especially in narrative forms. Three of the most expressive uses of 3 come from Judaism/Christianity, Hinduism and Taoism. 3 is a significant number in Christianity because of the Father, the Son and Holy Ghost. 3 is important in Hinduism because of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma. And 3 is important in Taoism because of the positivity, negativity and balance in the taijitu. Each of these examples paints a picture of two extremes and a counterbalance. For Christianity there is the Father on one extreme and the Son on the other, but both binding them together and transcending them is the Holy Ghost. In Hinduism, Vishnu is the creative force of the universe and Shiva is the destructive force; two extremes that are mediated between by Brahma, the preservative force of the universe. In the Taoist taijitu, things become most simple, there is the extreme negative and the extreme positive put in a dichotomy, but kept in balance via their meeting. Binding and transcending each of these trichotomies is the idea of 2+1 as an equation for being. This is reprised by Newtonian theory that suggests for each force there is an equal an opposite (F1 = −F2); and in such, there is balance in the world. Newton, later Einstein and other physicians, have formulated this view of the world that we deem realistic and accurate whilst humans across the world have always been trying to articulate it. Whilst Newton says F1 = −F2, the Hindus, for example, suggest that on one hand there is destruction, on the other creation, and keeping them in harmony is preservation. These ideas manifest as truths of different qualities - Hindu philosophy and Newtonian physics are, let me emphasise, not the same - but my point is not to conflict science and philosophy. Let us then draw up one more example. We all hold two extreme ideas of what was and what is. These are extremes quite equal to the Christian father (past) and son (present). However, to unify past and present we use the idea of progression, and thus emerges a direction of time that extends into the future. And the future is always looming (you could say a little like the holy ghost is). Again, my point here is not to suggest that the world of symbols is equal to the world of science/facts. Rather, my point is that the world of symbols reflects the world of facts in a manner that is so often perceived as profound and meaningful. Specifically in regards to the idea of 3, this phenomena manifests with religious trichotomies. And, I am of course making this point to suggest that, just maybe, the reason why the classical fidget spinner has three lobes, and in turn, is so fascinating to us, is because we are inherently fascinated by 3. The fidget spinner, as not just a toy, but a mandala, situates the universal trictotomy of positive, negative and balance; father, son, spirit; destruction, creation, preservation around a centre - the individual - and we spin it as a means of acting out life. Playing with the fidget spinner is to act out the philosophy that, to live is to be surrounded by forces of positivity, negativity and balance chasing one another's tale.

This pretentious, but maybe fascinating, interpretation of the fidget spinner is something that I am mentioning because it occurred to me in parallel with my reading of Jung. What I now then want to present to you, however, is a mandala of my own that, not only combines Jung and the fidget spinner as a mandala, but gives us a novel pathway towards what I believe is some powerful film theory. To start this new line of thought, I want you to imagine the perspective of a binary star:

If you are one of these stars, and you are spinning around the other in such a way that you are always facing them - which is to say, as you spin around them, you are pivoting to keep a focus on them; you are in rotational balance - will you perceive them to be moving around you, or will you be moving around them, or you will you sense that you are moving around one another, or will nobody seem to be moving at all? And consider the fact here that, in a dark void of gravity-less, absolute space, you have no reference apart from the object in front of you.

I have been thinking about this for a while and I haven't been able to come upon any concrete answers. However, what brought me towards these thoughts was initially a conceptualisation of a two-lobed fidget spinner. If you were in one of the holes, would you sense that the other is forcing you to spin, or would you feel that it was yourself causing the motion, or could you sense that it was both of you/none of you?

These, I have to admit, are probably stupid questions that many of you are palming yourself in the forehead over. However, the idea within here is simply one of perspective. And outside of a psychical realm, within a symbolic one, this question of perspective links to the idea of two extremes spinning around one another. And it simply asks, how does one extreme see the other as they spin? If we map this idea onto positive and negative, masculine and female, anima and animus, we have an allegory of sorts that models the dance between masculine and feminine that we all encounter in life onto a mandala. And so this is what I have tried to manifest:

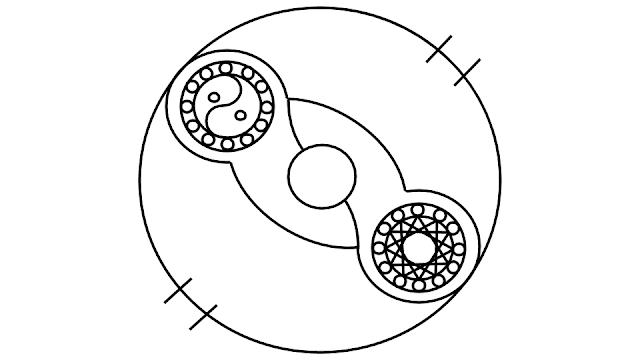

This mandala I have created is a syzygetic mandala. Syzygy is a term that Jung uses to describe the pairing of anima and animus, masculine and female. What I have drawn up is, essentially, a two-lobed fidget spinner floating in space. In one lobe, the higher lobe (though, due to the symmetry, there is no strict higher or lower) I have recreated the simplified taijitu as to represent Eros. Jung describes Eros in connection with the anima as presiding over the female consciousness as a great binding force. I have characterised it with the taijitu as it is a symbol of balance and binding - positive and negative coming together. In the other lobe I have presented a 12 pointed star. This represents Logos, which, as Jung suggests, is the logic and reason that presides over the animus. The 12 pointed star is then reaching out to the 12 orbiting globes around it; it is investigative and adventurous. The globes are presented to look like the ball bearings of the fidget spinner...

... as to imply that they make the rotation of Logos and Eros (as if they were binary stars) in the outer-lobes smooth. However, the globes serve a further purpose as a multiple of 3, and so represent the trichtomy we have discussed already. I have multiplied the trichotomy by four as to represent the trichotomies that are present in anima, animus, Logs and Eros. Each element is individual and requires attention to remain balanced between positive and negative. The 12 globes are Eros, positive, negative and balance; Logos, positive, negative and balance; anima, positive, negative and balance; and animus, positive, negative and balance. They all orbit an individual's Logos and Eros, which the taijitu and 12-pointed star represent, letting them spin in place as they watch one another like binary stars.

In the centre, you will see an empty circle. This is Aion: life. Aion mediates between Eros and Logos because life itself is in a balance between masculine and feminine; it controls them a little like the outer circle contains the two serpents in the taijitu, but, where the positive and negative are contained in the taijitu, they are made to spin in the syzygetic mandala. And the construct holding these three spheres together is split in half as to allude to the divide and to re-represent the taijitu.

All of these constructs are kept within a sphere as to represent the universe. The universe is broken with the four lines, however, because the universe must be perceived by a human eye as to be seen holding masculine and feminine. When we think of the universe in such terms, 'the universe' becomes 'our personal universe'. The sphere is broken to remind us that there is space beyond what we may perceive to be representing us and our perspective; the real universe lies beyond the personal universe. As a result, this mandala simultaneously represents the personal syzygy within ourselves and the collective syzygy in the wider universe, emphasising the thin divide between the two.

Overall, the mandala represents Eros and Logos floating around Aion in the universe. If this represents reality, then this is tantamount to the taijitu. However, if we consider this a receptacle for archetypes, the universe is in fact our psyche. Within our psyche is masculine and feminine and they revolve around the self, which is Aion: life or the idea of lifespan. The mandala emphasises the rotational ability of this dichotomy; Eros and Logos orbit one another and the self. The conflict that this produces is one of perspective; of Eros and Logos struggling to relate to one another and remain in a balance. In the most basic sense, this mandala is then trying to show the same struggle that Jung does in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious between anima and animus and the collective and personal unconscious; between myself and other; between the self I hold within me and the other that is within me as well as my self that I see around me and the others that I see around me.

I bring this up as this leads us into a new realm of thought. It is hard, in life, to perceive ourselves in relation to our opposite. The most fundamental self and opposite is the yin and yang; it is the anima and animus. Narratives are so fascinating as they challenge our own syzygetic composition. That is to say, narratives can challenge our animus with representations of the male that are contradictory. Likewise, narrative can challenge our anima with representations of the female that are in conflict with our perception. We can think of this as the challenging of the syzygetic projection. However, whilst the projection of our own personal syzygy creates friction in the space between ourselves and cinema, our biases can lead us astray. In such, we can become possessed to a degree by our own projections. And this means that, if we have a certain view of the masculine in the world, but see a contradictory view presented and choose to disregard it on only temperamental basis, that we have become possessed by bias. This is a fundamentally illogical way of approaching narrative as we choose to approach story as if it serves us, rather than challenges us. Feminist film criticism often deals with this realm of spectatorship. In such, it is almost always asking why females and males are presented certain ways. In asking this, you can realise the flaws and problems in the subtext of films that can sometimes only serve the biases in men and women. Sometimes, however, one can become possessed by an ideology and, instead of investigate film, expect it to operate in certain ways as to fit one's view of the world. We have talked about this divide a lot when discussing Amélie, and so we won't venture there again. Instead, what I want to do today is contrast two views of Disney's Moana as to demonstrate how one's internal syzygy effects how we perceive the subtext of a film.

I have already given my view on Moana's symbolism, and this view in many ways resonates with a video essay I am about to show. However, whilst I think that the subtext of Moana is strong and cohesive, Pageau seems to view the film as semiotically faulted because the masculine is simply replaced by the feminine whilst the presented masculine is bashed.

Pageau's analysis here is excellent, far deeper and precise than that which I offer. However, he seems to view the film as a twisted masculine hero narrative. In such, expectations of the presence of the masculine become paramount for his criticism. However, what I proposed was an analysis that saw this as a female hero myth about the female element of this world correcting itself and its masculine counterparts. And whilst this comes loaded with negative masculine archetypes, I don't think presenting men as negative is a no-no, and nor do I think presenting men as positive is a must. The same could be said in reverse; it is not wrong to show a negative female archetype, and it is not wrong to not show a positive female archetype. What is represented and not represented depends on the kind of story one wants to tell. And Moana seems to be about a reconciliation with the mother and father simultaneously. Moana's journey is then one that is meant to strengthen the masculine in her society - which has become female-dominant due to her father's own fears. She is tasked to bring adventure back into her society because her father, out of fear and tragedy, lost his sense of adventure. Simultaneously, she pulls Maui back into his role of uplifting society. He, after all, has become jaded and egotistical. Moana's response to the lack of positive masculinity is to reinvigorate those fires whilst putting out the fire within herself to a degree. She then transforms Te Kā into Ti Fiti only after having formed a relationship with the masculine.

Pageau analyses the design of the given world as one in which female reigns and builds his criticism from this foundation. He would rather there be a world in which masculine and female are in balance before the narrative starts. Why? With the world presented as female-centric, we know there is something wrong. The world is tantamount to a household in which a father has become sullen whilst the mother has become tyrannical. The mother became tyrannical because the father became obsessed with giving his children all that they wanted; he started to become their oedipal mother. When the mother becomes tyrannical, the children cower in the shadow of Eros; the adventurers stop adventuring and become a gathering society; they become female themselves. This over-abundance of the female presence gives rise to an anomalous female who is guided by her animus out into the waters. The daughter confronts her own mother. This is a story quite like Mulan in which, to defend the motherland and preserve her father, a woman must become a hermaphrodite of sorts. However, in becoming hermaphroditic, the female finds the path back to purer femininity by reconciling with the mother and forming a bond with a male. In joining forces with Maui, Moana confronts the tyrannous mother archetype and fosters masculinity in her tribe. Does this mean that she will remain a man, that she has placed the feminine symbol on the highest point of her island as to stop its growth? I'm not sure. If you assume that this narrative could only work with a male lead, then the answer would be tantamount to that which Pageau presents. However, if you follow the story as a female hero myth, we can assume that having put a balance between masculine and female, having made her tribe both hunter (masculine) and gather (female) again, that Moana will found new island tribes. These new tribes won't, due to a tradition of exploration being embedded into them, remain stagnant gatherers. This is what the shell on the top of the previous island represents. The island became female, and in doing so tried to ascend to heaven, which, narratives such the The Tower of Babel perceive as foolish. Moana urging her tribe to search the world, not only reach upwards to the heavens, is the female force within the tribe wanting the domain of the feminine to be expanded so that it can be organised and uplifted by the masculine who operate in it. In short, you may say that Moana is a story of a wife wanting a new, better house. And what is wrong with this? The female urges and goes forth with the male to conquer greater realms. And this is what Maui would continue to do in the end of the film; within the new, greater domain of the female, Maui would have the chance to bring more islands up and serve his duty in parallel to Ti Fiti.

The statement made to the masculine by Moana is, let the female grow and expand, and you will find greater responsibility and a greater domain to conquer. And this is not a poisonous statement. We can think of it as tantamount to a father letting his daughter become a woman. In nurturing this process, the father opens up a whole new world of different responsibilities for himself that will potentially see him become a better man. This is what happens with Maui. Whilst he is humbled by Ti Fiti in the end of the film, he is also given the opportunity to be a better person and confront larger goals as humans spread across the world. This doesn't sound like man-bashing to me. Sure, men are given a poke. And, no, I wouldn't say that the film couldn't do better, but, I think it says more than Pageau suggests. And let it not be forgotten that the narrative commentary is directed mostly towards the female as a female hero narrative; one that says women should confront the tyrannous mother and engage the sense of adventure and masculinity that she may be seeing as missing from society. (These statements, if I may note, are stuttered and, ultimately, are failed to be articulated in Tangled and Frozen - in Frozen the failure is more intense, Tangled just feels flat and un-fairy-tale-like).

The point that can be made by contrasting the results of Pageau's approach and my approach concerns syzygetic projection. In looking at Moana as it wants to be seen, rather than how we may want to see it based off of our own preconceptions and syzygetic temperament, we can learn a bunch. This is not to say that we are always wrong in projecting our sense of balance onto the world. However, when it concerns narrative, we have the opportunity to test such things. We can have our anima and animus confronted quite comfortably, and from the conflict between ourselves and the other we are presented with understanding. And such brings us back to the syzygetic mandala:

Masculine and female revolve around each other. Conflict comes from the revolution because perceiving one another in motion is difficult; it is hard to know who is spinning and how. Alas, by realising the masculine and female in ourselves, we can have a conversation manifest between all masculine and female syzygies whether they be in ourselves, in others, in reality or apart of the collective unconscious. To look at film in such a way is to engage a syzygetic gaze, a gaze that seeks to understand the differences and similarities between the personal syzygy and the presented syzygy. This allows us to step away from more basic and clunky ideas of a female and male gaze and allows us to recognise that the female and male gaze are always bound to one another; the test of narrative is so often realising how they are bound, and the reward of narrative is seeing our own syzygy reflected back at ourselves.

What I finally want to emphasise before ending is the difference between syzygetic projection and a syzygetic gaze. The projection is unconscious and it can lead to biased readings that fail to reflect anything back at ourselves. The gaze is conscious and seeks to see ourselves reflected back at ourselves. It is important engage the gaze as well as project as it allows for a communication between multiple levels of the syzygy manifestation. This is how we open up our lives to narrative and, not just criticise and force our perspective onto ourselves through film and narrative, but learn via introspection with film and narrative as coaches of sorts. The point made with Moana is then only a small part of a much bigger equation, one that concerns trying to see the other as ourselves before seeing ourselves in others. And so to reduce much of this down to the most basic assertion, I think it is best to ask how a narrative is already embodying a syzygy of its own composition before questioning how it is not embodying a syzygy, or our own specific syzygy.

Previous post:

Drama & Archetype - Surface And Deep Archetypes In The Exploitation Space

Next post:

Three Colours: Red - Colour Symbolism: Beauty-Complexity

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

This post does not engage Moana directly, but uses it to analyse the ways of approaching narratives as embodiments of yin and yang.

The fidget spinner. I have recently been immersing myself in a lot of Jung. In fact, for quite a while now I have been coming to terms with some of his key ideas (anima, animus, Logos and Eros in particular) and listening to chapters of Aion. More recently, however, I have started working my way through The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. And in conjuncture with this, my thoughts have wandered towards the fidget spinner.

The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious is a volume of Jung's essays that seems to define him in his most abstract and, to me, fascinating lights. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious deals with the human psyche as caught between biological and Freudian psychology. Whilst biological psychology considers all to do with the psyche in regards to the material body as it has evolved over hundreds of thousands and millions of years, and whilst Freudian psychology deals with the psyche as a product of, primarily, childhood, Jung deals with the psyche as reflective of mythological tropes that are thousands of years old and in regards to the individual's interaction with them from a young age. Jung then investigates the psyche and essential humanity as something given and, to a degree, taken. He refers to his key theoretical entities, the archetypes, as equivalent to Plato's Ideas. There are thousands of words that could be written about that sentence alone, but, one key concept that I want to highlight is that, in alluding to the Platonic 'Idea', Jung is alluding to the products of conscious being - thoughts of, exploring and defining form; ideas - as gifts given. One does not make an idea. An idea, when it is beyond mere opinion, when it is a fact reflective of reality, is accepted from a realm transcendent of ourselves. This indeed sounds highly metaphysical, but Jung emphasises that such an idea is far from this. Jung's archetypes are Ideas as images: imagos. The imago is the picture we create of someone, and it is often not a completely realistic one as it lends itself to bias, exaggeration and idealisation. Nonetheless, the imago as 'Idea as image' and 'archetype' is not constructed singularly by an individual. Like ideas are considered by Plato as gifts from the abstract, stars plucked out of the heavens, archetypes emerge from the collective unconscious in accordance to Jung. And the collective unconscious, a relatively simple idea, is a conceptualisation of all shared human thoughts and traits; the collective unconscious is made up of everything that, to a good degree, is in all people. It is all the unconscious thoughts and predispositions we share.

The archetype as a product of the collective unconscious is what necessitates a study of mythology, fairy tale and religion for Jung, for these are collections of unconscious imagos, characters and narratives that form a library and history of human thought. Whilst mythology is not the birthing point of archetypes, they reflect the most fundamental Ideas that humans, conscious or not, gleaned from the universe. As a result, to understand Jung's archetypes, especially the anima and animus, which are arguably the most important archetypes, one must start with a conceptualisation of the universe. Ironically, we will have to conceptualise of the universe in terms of ourselves, in reference to mythology and Ideas of the collective unconscious. This, however, will make clear why Jung is so insistent upon the personal unconscious as intrinsically bound to the collective unconscious.

We would all be very familiar with this symbol. This is the simplified representation of the taijitu. It emerges from Chinese philosophy and Taoism and is a mandala. In such, it represents the universe. The universe, the circle, is made up of a duality; negative and positive. However, in the negative and the positive are attributes of the antithesis, implying that positive can come from negative, that negative can come from positive and that the two are only in balance when such is the case. The negative and the positive are abstract, non-concrete ideas. In such, they can be seen to represent dark and light, passive and active, male and female, etc.

In the realm of the taijitu, and, indeed, in the realm of Jung, too, it seems that masculine and feminine pre-exist the human man and woman. And this is a profoundly important element of Jungian archetypal theory. Men imitate the 'masculine' side of the universe whilst women imitate the 'feminine' side of the universe. Jung is wary about defining what masculine and feminine mean in these regards, but, with anima and animus, he alludes to the 'soul' (anima; female) and 'heart' (animus, male). In alluding to this, he immediately emphasises that he does not want to invoke dogmatic conceptions of either male or female, rather, only wants to enter a realm in which we intuit what is masculine and what is female, not just in regards to our culture and society, but in regards to the conception of the universe we inherit from the collective unconscious. Jung, in this sense, does not believe that male and female are merely social constructs; they reach deep into human history and, quite essentially, transcend it. Furthermore, Jung believes that the collective unconscious has understood, and so represents, truth.

Archetypes are the manifestation of truth. However, they are not pure. Archetypes are mapped onto the world, they are imagos, and thus they become social constructs to a degree. Moreover, they can become pathologised; made receptacles for all of our complexes. The anima and animus are then not yin and yang; they are our idea of the ultimate female and male, and, in turn, they are idols of yin and yang held in our psyche. In turn, they can be corrupted if we do not monitor and work with them consciously. Alas, let's take a step back. Fidget spinners.

What I want to take you through is a thought experiment that questions what the fidget spinner may symbolise if it, itself, is interpreted as a mandala. To start the thought experiment, we should recognise that the fidget spinner was designed to capture the attention of people (children and young people) who fidget. There were claims that it could help people with ADHD and autism, but these claims are not scientifically supported.

I think it would be fair to say that, in complete ignorance of the toy's purpose, the fidget spinner became a huge fad product. I think it has gone away by now. There are multiple videos online of people using pressurised air to make them spin ridiculously fast and, in addition to this, people have set them on fire and turned them into weapons - and then, I'm sure, made them spin at thousands of rotations per second. This would indicate that the toy has ran its due course. Alas, why did it become so popular?

Most simply, the toy is mildly captivating and a physical novelty; it spins at a faster rate that you'd think having not spun one and so the sensation of it spinning on your finger is fascinating. If we were to delve a little deeper, however, we could look at the design of the spinner.

What we have here is a central button, a ball bearing, surrounded by three weighted lobes. The lack of friction surrounding the central button and the balanced weight of the three outer lobes allows for smooth spinning. Moreover, the three holes make for an optical illusion as they spin. What is fascinating about this design here is the use of 3. Fidget spinners will work well with a various number of lobes; common designs range from 2-6. However, 3 is the primary design. This has much to do with size requirements and the device fitting in small hands. But, could we make a stretch and - just for the sake of analysis - question the three lobes as a symbolic reference.

3 and multiples of 3, 12 in particular, are numbers that people seem quite drawn to - especially in narrative forms. Three of the most expressive uses of 3 come from Judaism/Christianity, Hinduism and Taoism. 3 is a significant number in Christianity because of the Father, the Son and Holy Ghost. 3 is important in Hinduism because of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma. And 3 is important in Taoism because of the positivity, negativity and balance in the taijitu. Each of these examples paints a picture of two extremes and a counterbalance. For Christianity there is the Father on one extreme and the Son on the other, but both binding them together and transcending them is the Holy Ghost. In Hinduism, Vishnu is the creative force of the universe and Shiva is the destructive force; two extremes that are mediated between by Brahma, the preservative force of the universe. In the Taoist taijitu, things become most simple, there is the extreme negative and the extreme positive put in a dichotomy, but kept in balance via their meeting. Binding and transcending each of these trichotomies is the idea of 2+1 as an equation for being. This is reprised by Newtonian theory that suggests for each force there is an equal an opposite (F1 = −F2); and in such, there is balance in the world. Newton, later Einstein and other physicians, have formulated this view of the world that we deem realistic and accurate whilst humans across the world have always been trying to articulate it. Whilst Newton says F1 = −F2, the Hindus, for example, suggest that on one hand there is destruction, on the other creation, and keeping them in harmony is preservation. These ideas manifest as truths of different qualities - Hindu philosophy and Newtonian physics are, let me emphasise, not the same - but my point is not to conflict science and philosophy. Let us then draw up one more example. We all hold two extreme ideas of what was and what is. These are extremes quite equal to the Christian father (past) and son (present). However, to unify past and present we use the idea of progression, and thus emerges a direction of time that extends into the future. And the future is always looming (you could say a little like the holy ghost is). Again, my point here is not to suggest that the world of symbols is equal to the world of science/facts. Rather, my point is that the world of symbols reflects the world of facts in a manner that is so often perceived as profound and meaningful. Specifically in regards to the idea of 3, this phenomena manifests with religious trichotomies. And, I am of course making this point to suggest that, just maybe, the reason why the classical fidget spinner has three lobes, and in turn, is so fascinating to us, is because we are inherently fascinated by 3. The fidget spinner, as not just a toy, but a mandala, situates the universal trictotomy of positive, negative and balance; father, son, spirit; destruction, creation, preservation around a centre - the individual - and we spin it as a means of acting out life. Playing with the fidget spinner is to act out the philosophy that, to live is to be surrounded by forces of positivity, negativity and balance chasing one another's tale.

This pretentious, but maybe fascinating, interpretation of the fidget spinner is something that I am mentioning because it occurred to me in parallel with my reading of Jung. What I now then want to present to you, however, is a mandala of my own that, not only combines Jung and the fidget spinner as a mandala, but gives us a novel pathway towards what I believe is some powerful film theory. To start this new line of thought, I want you to imagine the perspective of a binary star:

If you are one of these stars, and you are spinning around the other in such a way that you are always facing them - which is to say, as you spin around them, you are pivoting to keep a focus on them; you are in rotational balance - will you perceive them to be moving around you, or will you be moving around them, or you will you sense that you are moving around one another, or will nobody seem to be moving at all? And consider the fact here that, in a dark void of gravity-less, absolute space, you have no reference apart from the object in front of you.

I have been thinking about this for a while and I haven't been able to come upon any concrete answers. However, what brought me towards these thoughts was initially a conceptualisation of a two-lobed fidget spinner. If you were in one of the holes, would you sense that the other is forcing you to spin, or would you feel that it was yourself causing the motion, or could you sense that it was both of you/none of you?

These, I have to admit, are probably stupid questions that many of you are palming yourself in the forehead over. However, the idea within here is simply one of perspective. And outside of a psychical realm, within a symbolic one, this question of perspective links to the idea of two extremes spinning around one another. And it simply asks, how does one extreme see the other as they spin? If we map this idea onto positive and negative, masculine and female, anima and animus, we have an allegory of sorts that models the dance between masculine and feminine that we all encounter in life onto a mandala. And so this is what I have tried to manifest:

This mandala I have created is a syzygetic mandala. Syzygy is a term that Jung uses to describe the pairing of anima and animus, masculine and female. What I have drawn up is, essentially, a two-lobed fidget spinner floating in space. In one lobe, the higher lobe (though, due to the symmetry, there is no strict higher or lower) I have recreated the simplified taijitu as to represent Eros. Jung describes Eros in connection with the anima as presiding over the female consciousness as a great binding force. I have characterised it with the taijitu as it is a symbol of balance and binding - positive and negative coming together. In the other lobe I have presented a 12 pointed star. This represents Logos, which, as Jung suggests, is the logic and reason that presides over the animus. The 12 pointed star is then reaching out to the 12 orbiting globes around it; it is investigative and adventurous. The globes are presented to look like the ball bearings of the fidget spinner...

... as to imply that they make the rotation of Logos and Eros (as if they were binary stars) in the outer-lobes smooth. However, the globes serve a further purpose as a multiple of 3, and so represent the trichtomy we have discussed already. I have multiplied the trichotomy by four as to represent the trichotomies that are present in anima, animus, Logs and Eros. Each element is individual and requires attention to remain balanced between positive and negative. The 12 globes are Eros, positive, negative and balance; Logos, positive, negative and balance; anima, positive, negative and balance; and animus, positive, negative and balance. They all orbit an individual's Logos and Eros, which the taijitu and 12-pointed star represent, letting them spin in place as they watch one another like binary stars.

In the centre, you will see an empty circle. This is Aion: life. Aion mediates between Eros and Logos because life itself is in a balance between masculine and feminine; it controls them a little like the outer circle contains the two serpents in the taijitu, but, where the positive and negative are contained in the taijitu, they are made to spin in the syzygetic mandala. And the construct holding these three spheres together is split in half as to allude to the divide and to re-represent the taijitu.

All of these constructs are kept within a sphere as to represent the universe. The universe is broken with the four lines, however, because the universe must be perceived by a human eye as to be seen holding masculine and feminine. When we think of the universe in such terms, 'the universe' becomes 'our personal universe'. The sphere is broken to remind us that there is space beyond what we may perceive to be representing us and our perspective; the real universe lies beyond the personal universe. As a result, this mandala simultaneously represents the personal syzygy within ourselves and the collective syzygy in the wider universe, emphasising the thin divide between the two.

Overall, the mandala represents Eros and Logos floating around Aion in the universe. If this represents reality, then this is tantamount to the taijitu. However, if we consider this a receptacle for archetypes, the universe is in fact our psyche. Within our psyche is masculine and feminine and they revolve around the self, which is Aion: life or the idea of lifespan. The mandala emphasises the rotational ability of this dichotomy; Eros and Logos orbit one another and the self. The conflict that this produces is one of perspective; of Eros and Logos struggling to relate to one another and remain in a balance. In the most basic sense, this mandala is then trying to show the same struggle that Jung does in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious between anima and animus and the collective and personal unconscious; between myself and other; between the self I hold within me and the other that is within me as well as my self that I see around me and the others that I see around me.

I bring this up as this leads us into a new realm of thought. It is hard, in life, to perceive ourselves in relation to our opposite. The most fundamental self and opposite is the yin and yang; it is the anima and animus. Narratives are so fascinating as they challenge our own syzygetic composition. That is to say, narratives can challenge our animus with representations of the male that are contradictory. Likewise, narrative can challenge our anima with representations of the female that are in conflict with our perception. We can think of this as the challenging of the syzygetic projection. However, whilst the projection of our own personal syzygy creates friction in the space between ourselves and cinema, our biases can lead us astray. In such, we can become possessed to a degree by our own projections. And this means that, if we have a certain view of the masculine in the world, but see a contradictory view presented and choose to disregard it on only temperamental basis, that we have become possessed by bias. This is a fundamentally illogical way of approaching narrative as we choose to approach story as if it serves us, rather than challenges us. Feminist film criticism often deals with this realm of spectatorship. In such, it is almost always asking why females and males are presented certain ways. In asking this, you can realise the flaws and problems in the subtext of films that can sometimes only serve the biases in men and women. Sometimes, however, one can become possessed by an ideology and, instead of investigate film, expect it to operate in certain ways as to fit one's view of the world. We have talked about this divide a lot when discussing Amélie, and so we won't venture there again. Instead, what I want to do today is contrast two views of Disney's Moana as to demonstrate how one's internal syzygy effects how we perceive the subtext of a film.

I have already given my view on Moana's symbolism, and this view in many ways resonates with a video essay I am about to show. However, whilst I think that the subtext of Moana is strong and cohesive, Pageau seems to view the film as semiotically faulted because the masculine is simply replaced by the feminine whilst the presented masculine is bashed.

Pageau's analysis here is excellent, far deeper and precise than that which I offer. However, he seems to view the film as a twisted masculine hero narrative. In such, expectations of the presence of the masculine become paramount for his criticism. However, what I proposed was an analysis that saw this as a female hero myth about the female element of this world correcting itself and its masculine counterparts. And whilst this comes loaded with negative masculine archetypes, I don't think presenting men as negative is a no-no, and nor do I think presenting men as positive is a must. The same could be said in reverse; it is not wrong to show a negative female archetype, and it is not wrong to not show a positive female archetype. What is represented and not represented depends on the kind of story one wants to tell. And Moana seems to be about a reconciliation with the mother and father simultaneously. Moana's journey is then one that is meant to strengthen the masculine in her society - which has become female-dominant due to her father's own fears. She is tasked to bring adventure back into her society because her father, out of fear and tragedy, lost his sense of adventure. Simultaneously, she pulls Maui back into his role of uplifting society. He, after all, has become jaded and egotistical. Moana's response to the lack of positive masculinity is to reinvigorate those fires whilst putting out the fire within herself to a degree. She then transforms Te Kā into Ti Fiti only after having formed a relationship with the masculine.

Pageau analyses the design of the given world as one in which female reigns and builds his criticism from this foundation. He would rather there be a world in which masculine and female are in balance before the narrative starts. Why? With the world presented as female-centric, we know there is something wrong. The world is tantamount to a household in which a father has become sullen whilst the mother has become tyrannical. The mother became tyrannical because the father became obsessed with giving his children all that they wanted; he started to become their oedipal mother. When the mother becomes tyrannical, the children cower in the shadow of Eros; the adventurers stop adventuring and become a gathering society; they become female themselves. This over-abundance of the female presence gives rise to an anomalous female who is guided by her animus out into the waters. The daughter confronts her own mother. This is a story quite like Mulan in which, to defend the motherland and preserve her father, a woman must become a hermaphrodite of sorts. However, in becoming hermaphroditic, the female finds the path back to purer femininity by reconciling with the mother and forming a bond with a male. In joining forces with Maui, Moana confronts the tyrannous mother archetype and fosters masculinity in her tribe. Does this mean that she will remain a man, that she has placed the feminine symbol on the highest point of her island as to stop its growth? I'm not sure. If you assume that this narrative could only work with a male lead, then the answer would be tantamount to that which Pageau presents. However, if you follow the story as a female hero myth, we can assume that having put a balance between masculine and female, having made her tribe both hunter (masculine) and gather (female) again, that Moana will found new island tribes. These new tribes won't, due to a tradition of exploration being embedded into them, remain stagnant gatherers. This is what the shell on the top of the previous island represents. The island became female, and in doing so tried to ascend to heaven, which, narratives such the The Tower of Babel perceive as foolish. Moana urging her tribe to search the world, not only reach upwards to the heavens, is the female force within the tribe wanting the domain of the feminine to be expanded so that it can be organised and uplifted by the masculine who operate in it. In short, you may say that Moana is a story of a wife wanting a new, better house. And what is wrong with this? The female urges and goes forth with the male to conquer greater realms. And this is what Maui would continue to do in the end of the film; within the new, greater domain of the female, Maui would have the chance to bring more islands up and serve his duty in parallel to Ti Fiti.

The statement made to the masculine by Moana is, let the female grow and expand, and you will find greater responsibility and a greater domain to conquer. And this is not a poisonous statement. We can think of it as tantamount to a father letting his daughter become a woman. In nurturing this process, the father opens up a whole new world of different responsibilities for himself that will potentially see him become a better man. This is what happens with Maui. Whilst he is humbled by Ti Fiti in the end of the film, he is also given the opportunity to be a better person and confront larger goals as humans spread across the world. This doesn't sound like man-bashing to me. Sure, men are given a poke. And, no, I wouldn't say that the film couldn't do better, but, I think it says more than Pageau suggests. And let it not be forgotten that the narrative commentary is directed mostly towards the female as a female hero narrative; one that says women should confront the tyrannous mother and engage the sense of adventure and masculinity that she may be seeing as missing from society. (These statements, if I may note, are stuttered and, ultimately, are failed to be articulated in Tangled and Frozen - in Frozen the failure is more intense, Tangled just feels flat and un-fairy-tale-like).

The point that can be made by contrasting the results of Pageau's approach and my approach concerns syzygetic projection. In looking at Moana as it wants to be seen, rather than how we may want to see it based off of our own preconceptions and syzygetic temperament, we can learn a bunch. This is not to say that we are always wrong in projecting our sense of balance onto the world. However, when it concerns narrative, we have the opportunity to test such things. We can have our anima and animus confronted quite comfortably, and from the conflict between ourselves and the other we are presented with understanding. And such brings us back to the syzygetic mandala:

Masculine and female revolve around each other. Conflict comes from the revolution because perceiving one another in motion is difficult; it is hard to know who is spinning and how. Alas, by realising the masculine and female in ourselves, we can have a conversation manifest between all masculine and female syzygies whether they be in ourselves, in others, in reality or apart of the collective unconscious. To look at film in such a way is to engage a syzygetic gaze, a gaze that seeks to understand the differences and similarities between the personal syzygy and the presented syzygy. This allows us to step away from more basic and clunky ideas of a female and male gaze and allows us to recognise that the female and male gaze are always bound to one another; the test of narrative is so often realising how they are bound, and the reward of narrative is seeing our own syzygy reflected back at ourselves.

What I finally want to emphasise before ending is the difference between syzygetic projection and a syzygetic gaze. The projection is unconscious and it can lead to biased readings that fail to reflect anything back at ourselves. The gaze is conscious and seeks to see ourselves reflected back at ourselves. It is important engage the gaze as well as project as it allows for a communication between multiple levels of the syzygy manifestation. This is how we open up our lives to narrative and, not just criticise and force our perspective onto ourselves through film and narrative, but learn via introspection with film and narrative as coaches of sorts. The point made with Moana is then only a small part of a much bigger equation, one that concerns trying to see the other as ourselves before seeing ourselves in others. And so to reduce much of this down to the most basic assertion, I think it is best to ask how a narrative is already embodying a syzygy of its own composition before questioning how it is not embodying a syzygy, or our own specific syzygy.

Previous post:

Drama & Archetype - Surface And Deep Archetypes In The Exploitation Space

Next post:

Three Colours: Red - Colour Symbolism: Beauty-Complexity

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack