Giuseppe Arcimboldo - Art In Association

Thoughts On: Famous Works by Giuseppe Arcimboldo: Vertunmus (1591), The Jurist (1566), Air (1566) & Allegory of Fire (1566)

A look into the logic underlying absurd Mannerist paintings.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo is an Italian painter, active from the mid to late-1500s, who is most famous for paintings in which he would composed portraits out of objects such as fruit. Here is his most famous painting, Vertumnus:

This is a complex painting that seems parodic and absurd at first, but in fact showcases just one of the diverse functions of Arcimboldo's style. Here, Arcimboldo produces a positive, rather romantic commentary on a character. Depicted here is Rudolf II:

Rudolf II reigned as Holy Roman Emperor between 1576 and 1612. He is often described as either simultaneously or separately an incompetent ruler preoccupied with the arts and cult science who catalysed crusades as well as a great ruler who contributed to culture and the scientific revolution. Arcimboldo paints him in a very positive light, capturing the latter opinion - being an artist himself, this isn't too surprising. He maps onto Rudolf's image the visage of Vertumnus, the Roman god of seasons and metamorphosis. The fruits he uses to construct his image are seemingly symbolic of the growth and cultural change Rudolf II is seen, by Arcimboldo, to have seeded. This can then be recognised as a regal depiction, rather feminine in symbolic character, calmly chaotic, curious, powerful and even intent on seduction...

What we can recognise here is Arcimboldo's layering of objects, executed with great precision and verisimilitude - which is to say that we can almost believe that someone would be able to glue these fruits together to create a real statue - used to induce association or attribution; we, the viewer, taking the symbolic and aesthetic value of the fruits and mapping them on to the constructed persona of Rudolf II. This is the fundamental purpose of his style. However, it is manipulated here, as said, to characterise a person positively and romantically. What is emphasised here is Arcimboldo's proclivity to provide his own personal commentary with his art, and we see this best with his juxtaposition of the already discussed Rudolf and his background.

So often in paintings of royalty, setting matters as much as subject; a queen positioned on a grand throne, a king on a shimmering steed or something of such a character.

Arcimboldo refuses this with his black, rough background. There is no setting, and so the supposed divinity of Rudolf is shown to emerge only from within himself, his character and his actions; there is no cloud split by light symbolising God's presence and appointment; Rudolf is a God - which is a rather radical statement considering this is a Christian ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

It is with this brief look at Vertumnus that it becomes easier to see through the surreal mode of representation Arcimboldo contrives and find logic and reason. From here, let us then look at a few more of his paintings. We start with The Jurist:

Here, Arcimboldo applies his style as he does in Vertumnus, yet to an antithetical effect, which is to say, where Arcimboldo's surreal construction shows Rudolf in a romantic light, the lawyer here is depicted in a defamatory light. Whether this is modelled after an actual person or not is unknown, so we cannot say if Arcimboldo speaks of all lawyers or just a specific individual, but, it seems obvious that this figure, symbolic or not, is not very much liked.

The face here is moulded out of chicken and fish: dead meat. What this represents is not easy to pin down, but it seems negative. It is possible that this suggests that the lawyer, in character and purpose, is as ugly as uncooked meat; when used, when cooked, the meat serves its purpose, but, in its raw form, remains ugly. If this formulates a commentary on an individual, this suggests that the lawyer is of some use, but should taken advantage of reluctantly; maybe he is a learned person, but not at all likeable, is expensive and unfair.

To consider this a commentary on all lawyers, we may see there to be utility and goodness (something equivalent to a cooked meal) in law, but folly and ugliness in the process of its application via lawyers. Lawyers are then stuffed with law, but, themselves, are raw meat. This painting - whether it be about a lawyer or just lawyers - then comments on the human folly that must deal with something of such importance that it transcends the individual: law.

Seen as negative commentary, one could characterise this painting as cynical, witty or cutting. However, many of Arcimboldo's contemporaries considered his work to be humorous absurdities. This perspective may sustain our ideas on what this painting says as a general comment on lawyers, but, from the point of view that Arcimboldo's work was absurdly comic, if this depicts an individual, we may just see it as a tease. Maybe the person in question didn't have nice skin, hair or a generally pleasing physiognomy. This may explain why he is constructed with dead meat; he just wasn't a good-looker, and such may be the depth of this painting's commentary.

If we step back and apply this surface analysis to Vertumnus, we could see Arcimboldo painting Rudolf II as a mere 'fruit', an eccentric fellow. This painting may then reveal parts of his personal character; his alleged bisexuality, his secluded nature, his unstable emotional/psychological being (he was prone to depression), etc. How valid this analysis is difficult to suggest, and it seemingly bears less veracity when applied here than when applied to the lawyer, but, here we find another way of finding logic and reason in Arcimboldo's style.

Moving on, we come to Air. This lacks the character study that is present in the previous two paintings and is seemingly a technical exercise. As a result, the process of attribution is reversed. Instead of seeing objects make up a person as we so far have, here we see objects in the rough shape of a person; the person is secondary to the birds, and so we see them over the man. This is especially true when we zoom in:

It is now rather difficult to see a person - I would argue that is is impossible to see a specific character. However, we do see Arcimboldo's incredible ability to embed weight and surreal verisimilitude into his collage.

Paying special attention to the hair, or rather, the plume of birds, we find volume, depth and come to assume that it is possible for these various birds to have assembled as such. What Arcimboldo does so well here is then manage space and shape, specifically placing objects and creatures in positions where only necessary detail is shown without compromising the rest of their unseen, but assumed, form; we only see bird heads, but can infer that they are standing on legs. Some suggest that it is Arcimboldo's foundation in stained glass window art that gave him the skills to assemble a precise, complex collage out of many individual parts. One may even argue that he contrives abstract, extreme stained glass paintings.

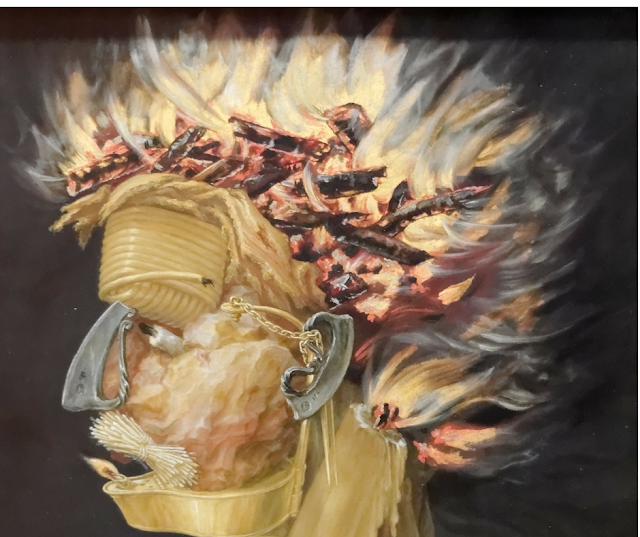

Moving away from more technical paintings, we come to what I find to be one of Arcimboldo's most fascinating paintings, Allegory of Fire:

This is not as striking or as technically perfect as Vertumnus - which we may call Arcimboldo's masterwork - however, its symbology and narrative techniques are stunning. Allegory of Fire, as the title suggests, builds a selection of metaphors upon one another, juxtaposing fire with humanity. To understand this, we must start with the eyes:

The candles here imply that fire is synonymous with vision, that it lights our way through life. However, here they are not lit. Above the fire is detonation cord. It makes up the forehead, which covers the prefrontal cortex of the human brain - the element of the brain that is and has historically been associated with higher human functions. Here a worrying thought is cast over human consciousness and higher function; what we see and think is juxtaposed with the potential for explosion and fettered light. Here we then have a blind human whose thoughts can ignite chaos.

Below the eyes is a mouth made of an oil lamp which breathes upon fire, which can speak into existence light, yet, if it speaks too much, if it exhales too much, this mouth may blow out the flame. Furthermore, the lips are made of seemingly flammable thickets. Again, there is imbalance and chaos here; the human body is shown as precariously mastering fire.

In the middle of the face are firesteels - metal used to strike a fire. These shape the ears and nose and so define the two receptive senses, implying that, if friction is produced in the process of hearing and smelling (possibly a metaphor for intuition; to smell a lie), light and/or destruction may follow.

Looking at this head in total, we see the senses and sensibilities of the human visage given the double quality that fire retains; a quality of utility and of decimation. This head and being is given life by the raging fire above, implying that it thinks, that it exists, that, just maybe, it is a little mad.

This head, it must be noted, is held up and kept aflame by a candle and the stand of the oil lamp. Much of the neck, in fact, seems to be made of wax, and so does the skin over the cheek. However, the flesh upon the face is said to be firestone. Nonetheless, it secures a melting and burnt aesthetic, implying that what holds up this head may collapse under pressure, in keeping it alive and burning. This sense of self-destruction becomes more complicated as we descend down to the body.

The foundations of this body, what the head works to operate, is firepower: mortars, canons and guns; a rather bold statement - a terrifyingly transparent one at that. Adorning this body, however, is a necklace and pendant, an Order of the Golden Fleece as well as an imperial double-eagle. The Order of the Golden Fleece is a Roman Catholic order of chivalry; something akin to, but more powerful than, a knighthood. The double eagle is a symbol of an empire. Both of these items are attributed to the royalty of Austria, the Hasburg House and Emperor Maximilian II - who is the beneficiary of this art-piece and those in its series. Not only would these items be forged by fire, but they give this painting a link to the extended human body, a society, an empire. Together, as the shoulders and chest of this person, they begin to literalise and map onto reality ideas of higher consciousness (royalty) and base destruction (firepower). These elements, hand in hand, are shown to formulate humanity.

In total, the commentary produced in this painting is expressive and succinct. It uses the theme or motif of fire to seed a narrative about human nature, our bond with fire and our flame-like qualities. Embodied by this painting and Arcimboldo's general style is then a narrative and allegorical capacity.

There is much more that could be said about Arcimboldo's work, but I hope we have shown today the breadths of its applications. Not only is this work surreal or humorous, but it can be precise, can produce negative and positive commentary, can produce and study of a character or an archetype and can reverse and play with processes of attribution to build an aesthetic or an idea. With that said, I leave things open to you. What do you think of Arcimboldo's work?

Previous post:

Pulgasari - Tyranny In The System

Next post:

End Of The Week Shorts #71

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

A look into the logic underlying absurd Mannerist paintings.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo is an Italian painter, active from the mid to late-1500s, who is most famous for paintings in which he would composed portraits out of objects such as fruit. Here is his most famous painting, Vertumnus:

This is a complex painting that seems parodic and absurd at first, but in fact showcases just one of the diverse functions of Arcimboldo's style. Here, Arcimboldo produces a positive, rather romantic commentary on a character. Depicted here is Rudolf II:

Rudolf II reigned as Holy Roman Emperor between 1576 and 1612. He is often described as either simultaneously or separately an incompetent ruler preoccupied with the arts and cult science who catalysed crusades as well as a great ruler who contributed to culture and the scientific revolution. Arcimboldo paints him in a very positive light, capturing the latter opinion - being an artist himself, this isn't too surprising. He maps onto Rudolf's image the visage of Vertumnus, the Roman god of seasons and metamorphosis. The fruits he uses to construct his image are seemingly symbolic of the growth and cultural change Rudolf II is seen, by Arcimboldo, to have seeded. This can then be recognised as a regal depiction, rather feminine in symbolic character, calmly chaotic, curious, powerful and even intent on seduction...

What we can recognise here is Arcimboldo's layering of objects, executed with great precision and verisimilitude - which is to say that we can almost believe that someone would be able to glue these fruits together to create a real statue - used to induce association or attribution; we, the viewer, taking the symbolic and aesthetic value of the fruits and mapping them on to the constructed persona of Rudolf II. This is the fundamental purpose of his style. However, it is manipulated here, as said, to characterise a person positively and romantically. What is emphasised here is Arcimboldo's proclivity to provide his own personal commentary with his art, and we see this best with his juxtaposition of the already discussed Rudolf and his background.

So often in paintings of royalty, setting matters as much as subject; a queen positioned on a grand throne, a king on a shimmering steed or something of such a character.

Arcimboldo refuses this with his black, rough background. There is no setting, and so the supposed divinity of Rudolf is shown to emerge only from within himself, his character and his actions; there is no cloud split by light symbolising God's presence and appointment; Rudolf is a God - which is a rather radical statement considering this is a Christian ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

It is with this brief look at Vertumnus that it becomes easier to see through the surreal mode of representation Arcimboldo contrives and find logic and reason. From here, let us then look at a few more of his paintings. We start with The Jurist:

Here, Arcimboldo applies his style as he does in Vertumnus, yet to an antithetical effect, which is to say, where Arcimboldo's surreal construction shows Rudolf in a romantic light, the lawyer here is depicted in a defamatory light. Whether this is modelled after an actual person or not is unknown, so we cannot say if Arcimboldo speaks of all lawyers or just a specific individual, but, it seems obvious that this figure, symbolic or not, is not very much liked.

The face here is moulded out of chicken and fish: dead meat. What this represents is not easy to pin down, but it seems negative. It is possible that this suggests that the lawyer, in character and purpose, is as ugly as uncooked meat; when used, when cooked, the meat serves its purpose, but, in its raw form, remains ugly. If this formulates a commentary on an individual, this suggests that the lawyer is of some use, but should taken advantage of reluctantly; maybe he is a learned person, but not at all likeable, is expensive and unfair.

To consider this a commentary on all lawyers, we may see there to be utility and goodness (something equivalent to a cooked meal) in law, but folly and ugliness in the process of its application via lawyers. Lawyers are then stuffed with law, but, themselves, are raw meat. This painting - whether it be about a lawyer or just lawyers - then comments on the human folly that must deal with something of such importance that it transcends the individual: law.

Seen as negative commentary, one could characterise this painting as cynical, witty or cutting. However, many of Arcimboldo's contemporaries considered his work to be humorous absurdities. This perspective may sustain our ideas on what this painting says as a general comment on lawyers, but, from the point of view that Arcimboldo's work was absurdly comic, if this depicts an individual, we may just see it as a tease. Maybe the person in question didn't have nice skin, hair or a generally pleasing physiognomy. This may explain why he is constructed with dead meat; he just wasn't a good-looker, and such may be the depth of this painting's commentary.

If we step back and apply this surface analysis to Vertumnus, we could see Arcimboldo painting Rudolf II as a mere 'fruit', an eccentric fellow. This painting may then reveal parts of his personal character; his alleged bisexuality, his secluded nature, his unstable emotional/psychological being (he was prone to depression), etc. How valid this analysis is difficult to suggest, and it seemingly bears less veracity when applied here than when applied to the lawyer, but, here we find another way of finding logic and reason in Arcimboldo's style.

Moving on, we come to Air. This lacks the character study that is present in the previous two paintings and is seemingly a technical exercise. As a result, the process of attribution is reversed. Instead of seeing objects make up a person as we so far have, here we see objects in the rough shape of a person; the person is secondary to the birds, and so we see them over the man. This is especially true when we zoom in:

It is now rather difficult to see a person - I would argue that is is impossible to see a specific character. However, we do see Arcimboldo's incredible ability to embed weight and surreal verisimilitude into his collage.

Paying special attention to the hair, or rather, the plume of birds, we find volume, depth and come to assume that it is possible for these various birds to have assembled as such. What Arcimboldo does so well here is then manage space and shape, specifically placing objects and creatures in positions where only necessary detail is shown without compromising the rest of their unseen, but assumed, form; we only see bird heads, but can infer that they are standing on legs. Some suggest that it is Arcimboldo's foundation in stained glass window art that gave him the skills to assemble a precise, complex collage out of many individual parts. One may even argue that he contrives abstract, extreme stained glass paintings.

Moving away from more technical paintings, we come to what I find to be one of Arcimboldo's most fascinating paintings, Allegory of Fire:

This is not as striking or as technically perfect as Vertumnus - which we may call Arcimboldo's masterwork - however, its symbology and narrative techniques are stunning. Allegory of Fire, as the title suggests, builds a selection of metaphors upon one another, juxtaposing fire with humanity. To understand this, we must start with the eyes:

The candles here imply that fire is synonymous with vision, that it lights our way through life. However, here they are not lit. Above the fire is detonation cord. It makes up the forehead, which covers the prefrontal cortex of the human brain - the element of the brain that is and has historically been associated with higher human functions. Here a worrying thought is cast over human consciousness and higher function; what we see and think is juxtaposed with the potential for explosion and fettered light. Here we then have a blind human whose thoughts can ignite chaos.

Below the eyes is a mouth made of an oil lamp which breathes upon fire, which can speak into existence light, yet, if it speaks too much, if it exhales too much, this mouth may blow out the flame. Furthermore, the lips are made of seemingly flammable thickets. Again, there is imbalance and chaos here; the human body is shown as precariously mastering fire.

In the middle of the face are firesteels - metal used to strike a fire. These shape the ears and nose and so define the two receptive senses, implying that, if friction is produced in the process of hearing and smelling (possibly a metaphor for intuition; to smell a lie), light and/or destruction may follow.

Looking at this head in total, we see the senses and sensibilities of the human visage given the double quality that fire retains; a quality of utility and of decimation. This head and being is given life by the raging fire above, implying that it thinks, that it exists, that, just maybe, it is a little mad.

The foundations of this body, what the head works to operate, is firepower: mortars, canons and guns; a rather bold statement - a terrifyingly transparent one at that. Adorning this body, however, is a necklace and pendant, an Order of the Golden Fleece as well as an imperial double-eagle. The Order of the Golden Fleece is a Roman Catholic order of chivalry; something akin to, but more powerful than, a knighthood. The double eagle is a symbol of an empire. Both of these items are attributed to the royalty of Austria, the Hasburg House and Emperor Maximilian II - who is the beneficiary of this art-piece and those in its series. Not only would these items be forged by fire, but they give this painting a link to the extended human body, a society, an empire. Together, as the shoulders and chest of this person, they begin to literalise and map onto reality ideas of higher consciousness (royalty) and base destruction (firepower). These elements, hand in hand, are shown to formulate humanity.

In total, the commentary produced in this painting is expressive and succinct. It uses the theme or motif of fire to seed a narrative about human nature, our bond with fire and our flame-like qualities. Embodied by this painting and Arcimboldo's general style is then a narrative and allegorical capacity.

There is much more that could be said about Arcimboldo's work, but I hope we have shown today the breadths of its applications. Not only is this work surreal or humorous, but it can be precise, can produce negative and positive commentary, can produce and study of a character or an archetype and can reverse and play with processes of attribution to build an aesthetic or an idea. With that said, I leave things open to you. What do you think of Arcimboldo's work?

Previous post:

Pulgasari - Tyranny In The System

Next post:

End Of The Week Shorts #71

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack