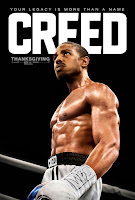

Creed - Where Is The Melodrama?

Thoughts On: Creed (2015)

Apollo Creed's son tries to anonymously rise into the professional boxing world with the help of an estranged uncle.

Looking forward to watching Creed II soon, I decided to sit down for the first Creed again. I remember liking this quite a bit when it first came out. What I saw this time, however, was far less impressive. What makes Creed work is Sylvester Stallone and its Rocky-isms. Many of these, such as the training montage, aren't very well done though. Seeing this, I have grown weary about Creed's sequel. To explore why, we will discuss the three or four notable missteps that I believe Creed makes as a Rocky film.

Firstly: realism. Rocky is a melodrama - understated and somewhat typhlodramatic, but primarily melodramatic. Melodrama is essential in the Rocky film for these are very much so narratives about the world coming into harmony; about chance in one's personal and professional life coinciding and fuelling an individual to grip what he has been so fortunate as to stumble upon and to live up to fate and a smile from destiny. Melos, dramatically speaking, requires an orchestration of narrative. Formulaic and rhythmic as it may be - predictable as it may seem - repetition in music, predictability in music, is a virtue, for it is music's capacity to pull you into its contrivance and structure that makes it so magical. Such is true of the musical drama - the melodrama. Rocky, the first two films especially, are perfect exemplars of just this. As the cliche goes, these films are not necessarily about the A and B, but the journey between the two. Creed's use of realism, its typhlodramatic basis, only serves to quash the affective abilities of melodrama. That is to say that the realist touches add not to our understanding of character and narrative; we feel not the harmony that Adonis strives for, that he must orchestrate with instruments of fate. With further expressionist melodrama, however, the palpable themes bubbling on the surface of this film would be allowed to strike out and resonate. We can come to a specific point of analysis briefly, but firstly, we must discuss a side-effect of the realism: meta-drama.

The first Rocky sees two actors step into a ring; two actors who look and dance like boxers. Rocky III strays from this with the injection of Hulk Hogan and Mr. T - both of which were pro-wrestlers. Rocky IV welcomes Dolph Lundgren, a genuine Kyokushin karate black belt and international champion. And of course Rocky V finally steps into the real boxing world to use Tommy Morrison - who essentially plays himself. This trend continues through Rocky Balboa and Creed with the use of real professional boxers who all play versions of themselves. Such details a way in which the Rocky series has gravitated towards realism and, in my belief, only to the series' detriment. The Rocky films, in my opinion, gain little from verisimilitude in the boxing sequences. As we see with the iconic editing and choreography in the first Rocky films, two athletic actors are more than enough--provide a scene with suitable verisimilitude and so give way to the development of genuine melodrama: story.

Ever since Rocky Balboa in particular there has been less focus put on the 'behind the scenes' of the boxing world and more focus put on some meta world in which Rocky was a real boxer; on actual conferences and a very present 'boxing world'. We feel almost no presence of a boxing world in the first two Rocky films. We see inside Apollo Creed's offices, we go into his home to see hate mail, but there are very fleeting moments in which there is a direct and real representation of a boxer's media obligations and professional life. The first two Rocky films are far more interested in the personal--only in the professional when the personal is embedded within it, or is expressed through it. A beautiful moment that expresses this in the first Rocky is one of the only conferences that we see. Instead of trying to answer reporters' questions, Rocky calls out through the TV to say hey to Adrian. And we watch this from their living room, we don't care to go to the conference itself. We only start to do these kind of things in Rocky III and V. In Rocky III, we start to see more of the professional life, but this is a signification that something wrong is occurring - that Rocky letting the media into his gym is going to destroy his career. This speaks volumes on the unattractiveness of the meta boxing world in my view. Alas, in Creed, there is an eagerness to move into the professional realm and present what TV shows provide. Such only feels disingenuous to me. I'd rather learn about personal struggles, see more training and character focus - for, as melodramatic as Rocky is, the first two had so much patience. They didn't care to throw in a few sequences of action in every 20 minutes. All the action comes at the end; melodrama and patient character observation first.

With many essential traits of the first two Rocky films - the traits that made them great - having been left behind by Creed, new things have been picked up. As in Rocky Balboa, aesthetics have been centralised and, to some degree, become a source of spectacle. We then see in the long take fighting sequences one of the most inane elements of Creed. Whilst film studies undergraduates and self-taught film buffs love a long shot, if those in Creed are questioned, they seem to fall apart. Primarily, it seems that the long shot is an expression of Coogler's realist approach. Without breaking the illusion of passing time with editing, Coogler has his audience feel a boxing match somewhat impressionistically; its tension, the changing of the upper hand, the chaos, the strain, etc. However, as previous Rocky film's prove, realism and verisimilitude help not in the boxing scenes; story, theme, archetypes, sound track and editing are those key elements that shake you to your bones. That is to say that Coogler's long shot is far from an improvement of the montages in Rocky IV, II and I. This is more than self-evident when you fall into these sequences, which begs the question, what is the function of the long shot in Creed? Is it merely a flashy attempt at shooting a scene uniquely?

Whilst more could be said, we have outlined some key ways in which Creed departs from the expected Rocky film without finding much success. I then believe the realism, the long shot, the meta world of real boxing, all harm narrative and drama before enhancing it. I leave things with you, however. How would you compare the early Rocky films and Creed?

Previous post:

The Cabin In The Woods - Why Watch Horror Films

Next post:

The Shop Around The Corner - Two (Faces) Into One

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

Apollo Creed's son tries to anonymously rise into the professional boxing world with the help of an estranged uncle.

Looking forward to watching Creed II soon, I decided to sit down for the first Creed again. I remember liking this quite a bit when it first came out. What I saw this time, however, was far less impressive. What makes Creed work is Sylvester Stallone and its Rocky-isms. Many of these, such as the training montage, aren't very well done though. Seeing this, I have grown weary about Creed's sequel. To explore why, we will discuss the three or four notable missteps that I believe Creed makes as a Rocky film.

Firstly: realism. Rocky is a melodrama - understated and somewhat typhlodramatic, but primarily melodramatic. Melodrama is essential in the Rocky film for these are very much so narratives about the world coming into harmony; about chance in one's personal and professional life coinciding and fuelling an individual to grip what he has been so fortunate as to stumble upon and to live up to fate and a smile from destiny. Melos, dramatically speaking, requires an orchestration of narrative. Formulaic and rhythmic as it may be - predictable as it may seem - repetition in music, predictability in music, is a virtue, for it is music's capacity to pull you into its contrivance and structure that makes it so magical. Such is true of the musical drama - the melodrama. Rocky, the first two films especially, are perfect exemplars of just this. As the cliche goes, these films are not necessarily about the A and B, but the journey between the two. Creed's use of realism, its typhlodramatic basis, only serves to quash the affective abilities of melodrama. That is to say that the realist touches add not to our understanding of character and narrative; we feel not the harmony that Adonis strives for, that he must orchestrate with instruments of fate. With further expressionist melodrama, however, the palpable themes bubbling on the surface of this film would be allowed to strike out and resonate. We can come to a specific point of analysis briefly, but firstly, we must discuss a side-effect of the realism: meta-drama.

The first Rocky sees two actors step into a ring; two actors who look and dance like boxers. Rocky III strays from this with the injection of Hulk Hogan and Mr. T - both of which were pro-wrestlers. Rocky IV welcomes Dolph Lundgren, a genuine Kyokushin karate black belt and international champion. And of course Rocky V finally steps into the real boxing world to use Tommy Morrison - who essentially plays himself. This trend continues through Rocky Balboa and Creed with the use of real professional boxers who all play versions of themselves. Such details a way in which the Rocky series has gravitated towards realism and, in my belief, only to the series' detriment. The Rocky films, in my opinion, gain little from verisimilitude in the boxing sequences. As we see with the iconic editing and choreography in the first Rocky films, two athletic actors are more than enough--provide a scene with suitable verisimilitude and so give way to the development of genuine melodrama: story.

Ever since Rocky Balboa in particular there has been less focus put on the 'behind the scenes' of the boxing world and more focus put on some meta world in which Rocky was a real boxer; on actual conferences and a very present 'boxing world'. We feel almost no presence of a boxing world in the first two Rocky films. We see inside Apollo Creed's offices, we go into his home to see hate mail, but there are very fleeting moments in which there is a direct and real representation of a boxer's media obligations and professional life. The first two Rocky films are far more interested in the personal--only in the professional when the personal is embedded within it, or is expressed through it. A beautiful moment that expresses this in the first Rocky is one of the only conferences that we see. Instead of trying to answer reporters' questions, Rocky calls out through the TV to say hey to Adrian. And we watch this from their living room, we don't care to go to the conference itself. We only start to do these kind of things in Rocky III and V. In Rocky III, we start to see more of the professional life, but this is a signification that something wrong is occurring - that Rocky letting the media into his gym is going to destroy his career. This speaks volumes on the unattractiveness of the meta boxing world in my view. Alas, in Creed, there is an eagerness to move into the professional realm and present what TV shows provide. Such only feels disingenuous to me. I'd rather learn about personal struggles, see more training and character focus - for, as melodramatic as Rocky is, the first two had so much patience. They didn't care to throw in a few sequences of action in every 20 minutes. All the action comes at the end; melodrama and patient character observation first.

With many essential traits of the first two Rocky films - the traits that made them great - having been left behind by Creed, new things have been picked up. As in Rocky Balboa, aesthetics have been centralised and, to some degree, become a source of spectacle. We then see in the long take fighting sequences one of the most inane elements of Creed. Whilst film studies undergraduates and self-taught film buffs love a long shot, if those in Creed are questioned, they seem to fall apart. Primarily, it seems that the long shot is an expression of Coogler's realist approach. Without breaking the illusion of passing time with editing, Coogler has his audience feel a boxing match somewhat impressionistically; its tension, the changing of the upper hand, the chaos, the strain, etc. However, as previous Rocky film's prove, realism and verisimilitude help not in the boxing scenes; story, theme, archetypes, sound track and editing are those key elements that shake you to your bones. That is to say that Coogler's long shot is far from an improvement of the montages in Rocky IV, II and I. This is more than self-evident when you fall into these sequences, which begs the question, what is the function of the long shot in Creed? Is it merely a flashy attempt at shooting a scene uniquely?

Whilst more could be said, we have outlined some key ways in which Creed departs from the expected Rocky film without finding much success. I then believe the realism, the long shot, the meta world of real boxing, all harm narrative and drama before enhancing it. I leave things with you, however. How would you compare the early Rocky films and Creed?

Previous post:

The Cabin In The Woods - Why Watch Horror Films

Next post:

The Shop Around The Corner - Two (Faces) Into One

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack