How Cinema Works (Expanded)

Thoughts On: Cinematic Function

An expansion of our theory of the cinematic space that attempts to answer a question of how cinema works.

We recently proposed a system of ideas that answered the question, How does cinema work? Our answer concerned a theory of the cinematic space and so dealt with the literal functioning of cinema as drama moves narrative. Due to its depth, the presented theory lacked certain details that I have since been working on and would like to use to expand our answer beyond dramatic narrative and to a totality of cinema. I would thus like to introduce this:

Inspired loosely by Taoist thought and the designs of Chinese philosophical icons found in places such as the I Ching, I have used the taijitu or bagua as an aesthetic, formal foundation for organising my ideas. What is fundamentally presented here is an up and a down, a give and a take that revolve around one another, grow and shrink respectively and in synchrony. This is the symbol of the taijitu, known as yin-yang. In addition to this is are surrounding blocks. These bear no relation to the hexagrams found in the I Ching. The hexagrams, a source of great complexity and, as some may know, Taoist divination, only inspire my relation of a core cycle to a larger cycle in cinema. Alas, though the above diagram is essential to our theory, we will start with a simpler diagram demonstrating the two key functional cycles in cinema:

These two diagrams are almost one and the same--the cinematic taijitu is merely more complex and expansive. What you will notice, however, is what I have presented here are the major elements of the cinematic space: 0, (, | | and S. We have explored these elements and their functioning before:

And furthermore, we have explored the foundational trichotomy in the cinematic space theory with a more simple exposition:

What we are to explore today are not going to be altogether new ideas. The step I would like to take today is integrative, and so concerns the combination of our many disparate ideas concerning the objective, subjective, concerning drama, concerning genre, mode, truth and more. We will only need to explore two key frameworks as to do this. Firstly, a theory of mimesis.

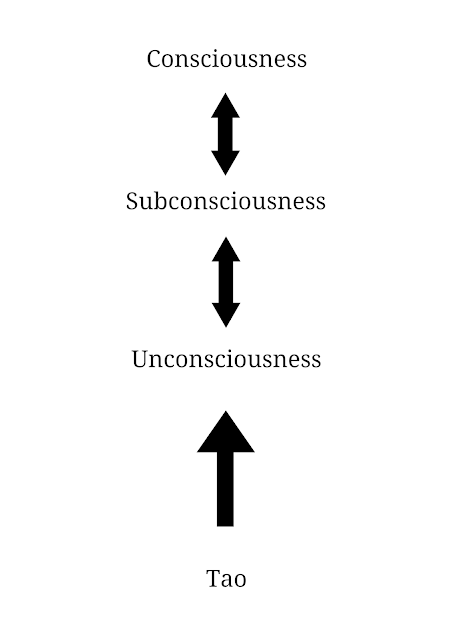

Our conception of mimesis, which is made up of known and known imitation, is one that means to take us through the Jungian depths of the mind and out into an abstract cosmological space one may equate to Tao. Consciousness, to Jung, is the highest manifestation of a reality principal in the human psyche; it is that which recognises the world and can simultaneously be accessed by the self and psyche. Consciousness deals with that which we know and know we know. Underneath this is a subconsciousness, what Jung would term the personal unconscious. This is a space of great impact, but, despite its deep foundations in the psyche and profound effect on conception, it often deals with reality in ways unknown to the self. Thus it is a place of the mind that interacts with the known in an unknown capacity. Below this is a deeper, darker unconsciousness which Jung terms the collective unconscious. This confronts the unknown elements of the universe, operating almost entirely unseen if not for the manifestation of symbolism, narrative and things alike in culture. The deepest depths of unconsciousness is too real to be human, so real that it becomes nature. Thus, it is a product of and imitative of the principals of fundamental reality in the universe around us - that which has been termed Tao in Chinese philosophy. Tao is unknowable and unknown, but the essence of consciousness itself.

Our exposition here is not necessarily psychological, psychoanalytical or philosophical. This is an ontology of art and narrative that Aristotle, albeit shakily, projects with his term mimesis. 'Mimesis' implies that, what manifests at the highest levels of tangibility and conception has foundations deeper than what is apparent; that what is is only so because it emerges from something that was, something that has always been. In narrative terms, what is consciously conceived and seen in art is then a product of subconsciousness, that a product of a collective unconsciousness, that an imitation of the essential reality, the absolute truths, of the universe. Such is a kind of logic followed by romantic theorist Friedrich von Schelling when he, in his book System of Transcendental Idealism, says:

What Schelling conceptualises as an 'unconscious infinity' underlying art and the human psyche, we conceptualise as Tao. It is not difficult to arrive at conclusions such as these for, one could argue, embedded in any theological structure figure-headed by a deity or supreme, creationary force is the fundamental assertion that what is is a manifestation of what was and that such has always been. We see this, too, in science. How, after all, can truth be measured if not with the assumption that truth exists and always has; that what can be presently measured is an indication of the histroical foundations of reality if understood wholly? Our hierarchy is nothing of a revelation, it is simply a basic distillation of uncomplicated logic that we can simplify as such:

Whilst Jung always struggled to suggest, sometimes neglected entirely, where the collective unconscious emerged from, what his archetypes that make up this realm were imitative of, we can make a simple extrapolation from his work and put his conception of fundamental, collective unconsciousness in a cycle with Tao.

Here we see represented Tao (.) and unconsciousness (\). Whilst each level of the human psyche, its collective and personal unconscious and consciousness, interacts, formulating a spectrum of awakeness, there is a fundamental disconnect between the human body and nature. This can only be overcome via illusion and imitation: humanity integrating back into nature. Thus, the fundamental truth in reality can be seen to inform and be chased by the human psyche. This is why Tao and unconsciousness cycle one another. Such can be more profoundly demonstrated with reference to the taijitu:

The taijitu does not represent the basic idea of yin and yang that many hold. Far beyond dark and light, good and bad, yin and yang are fractions of Tao, and are thus unnameable, which is to say, they cannot be given a satisfactory, all-encompassing definition. Terms associated with yin, however, are darkness, negativity and passivity. In contrast, yang is light, positivity and activity. As implied, these two entities are not opposites despite being different. As fractions of Tao they are complementary, wholly existent together. The simplest way to then think of yin and yang is in terms of night and day. It is not that night and day oppose one another, but that day gives way to night, night gives way to day, that they cause and infer each other, one result of ten thousand being the human sleep cycle: we rest so that we can work, we work so that we can rest; we follow this cycle as to align ourselves with a higher ideal (maybe Tao). One can then associate yin with anything absorbative and passive and yang with anything expressive and active. This, indeed, is a foundational element of Taoist divination demonstrated by the I Ching. We can do this ourselves by associating yin, negativity, with Tao and unconsciousness with yang, positivity. For, in all mimetic endeavours, the unconsciousness is actively attempting to penetrate fundamental reason and truth, to somehow glean from the infinite and absolute. This infinite and absolute, Tao, is illusive and so it evades, it shrinks as unconsciousness grows, grows as unconsciousness shrinks, circles as the other circles. Alas, in the unconsciousness are markers of the ultimate nature (after all, unconsciousness is human nature). Likewise, in the ultimate nature, that which birthed humanity, is human nature. This dark is in light and light in dark; this is why they inherently chase one another.

Whilst it may be paradoxical to put Tao, that which births yin and yang, within the taijitu (which represents in its totality Tao), what we mean to imply with this central cycle between unconsciousness and something equating Tao is simply an interaction between human nature and the essence of nature. This is the essential formula of mimetic investigation and art. Let us not forget consciousness, however. Consciousness has its relationship with Tao via unconsciousness, diluted and confused as it may be. We can represent this as such:

This is the essential representation of mimetic investigation: human nature dances with absolute nature and consciousness tries to listen to their music.

Having understood this primary element of our theory, we can move onto an art-centric manifestation:

Here we have a hierarchical breakdown of a functioning art. The diagram may be easily followed, but let us delve into it.

Whilst the incentive for art may arise from unconsciousness, from the universe itself, the first concrete step of art's creation is a conscious decision. This decision leads to the founding of a medium. For example, if the first caveman wants to draw, he will have to found the medium of painting to do this. In founding this medium, however, the caveman immediately initiates a trichotomy, an objective-subjective construct between an artist, an audience and a medial object. We have explored this concept before thusly:

Art is a manifestation of these three entities. For cinema, the subjective entity is an audience, a spectator of sorts. The objective entity is the screen and the technical constructs that the cinematic medium requires: as said, a screen, but also a camera, sound system, a set, actors, a script, etc. Presiding over these two, both objective and subjective, is the filmmaker. This is the basic trichotomy.

This trichotomy leads to the construction of an artistic space. We shall concern ourselves with the cinematic space. And, as we have explored many times over, the cinematic space is made up of four entities: drama, most foundationally, then mode, then logic and then style.

It is unnecessary for us to go into detail here as have done so before. We can, however, reduce our hierarchy to its basic symbols:

Now we understand this formulation, it must be highlighted that style connotes genre and that which associates one expression of a medium to multiple orders of others (expressions made by the same artist, those from a similar period, a singular movement, a sub-genre, genre, form, mode, etc). The style of a work can be thought of as that which binds directly to the conscious element of art. This implies a cycle.

Both cyclical and hierarchical, art is a movement between conscious intention and conscious re-invention. The first art work was a manifestation of consciousness meant to unite an artist, audience and medial object that was itself a construct of drama, mode, logic and style. The second work to manifest, however, would not just be a conscious construct, but a construct conscious of the art work that preceded it. Thus, embedded in any conscious decision to move into a medium and create a work is the soul of the endless works before it. Such is a key assertion of structuralist theory, and can is expressed by a figure such as Northrop Frye in his Anatomy of Criticism:

It is clear that I am not in complete agreement with Frye as he refuses to move out of a classically structuralist realm of the artistic space (that which I deal with only with drama, mode, logic and style). Alas, he shines light on the link between created works and the process of creating new works, between style (genre) and consciousness.

Having understood that art is a mimetic function predicated on a cycle between unconsciousness and the essence of nature and that it manifests as a movement between conscious creation and recreation, we can arrive at a dual cycle that reveals a more cohesive picture of what an art, cinema, is and how it functions.

The major revelation in the combination of these two cycles concerns a formalisation of originality or individuality in artistic creation. It is not that literature creates literature, as Frye asserts, but that literature follows literature and simultaneously is created, always, out of consciousness that has its ear to the bedrock of unconsciousness and therefore can express truth in nature - that which may not be found in preceding literature. This is not to suggest that essential, absolute truth is stumbled upon by every individual piece of work, just that there is always the potential for a new resonance between human and reality.

Our final task now is to briefly expand upon the seven major elements bordering the central cycle of cinema. We can then explore the most complex manifestation of all we have so far spoken of with this:

As you should be able to recognise, this is a direct manifestation of the previous dual cycle and so each component has a character we have spoken of before. Let us make this obvious with annotation:

Represented here are the components of consciousness, medium, trichotomy, drama, mode, logic and style. We start with consciousness.

Rather simply, consciousness is made up of the Jungian tripartite: consciousness, personal unconscious and collective unconscious - a trichotomy I usually reduce to consciousness, subconsciousness and unconsciousness. It is only important to note here that unconsciousness, the bottom entity, is not fully represented. It is present here as an entity connecting this conscious element down to the unconsciousness that circulates Tao.

Next, we have medium. I have represented this simply with two blocks together symbolising a definition of medium to be technological expression. I then assert with this that any given medium is a determination of expression - for example, cinema wants images to move - and technology - to make images move, the cinematic camera had to be invented. Medium is an abstract concept, but all mediums may be differentiated on the grounds of both technology and expression, indeed, this is how we define and categorise them. Sculpture means to express life with tools such as chisels and media such as stone; painting, too means to capture life, its chosen tools are a canvas, a brush and paint; theatre has its expressive yearnings and uses the performing body and script to do so. Expression unites all mediums, technology differentiates them and informs the typology of expression.

Here we have represented the tripartite. We have discussed these elements already: the object, the subject, the mediator; the medial devices, the spectator, the artist; a screen, an audience, a filmmaker.

Here is drama. It is represented through three lines. The top line, split into two parts, symbolises the known and unknown mimetic functions explored here. In addition to this are the five types of drama: biodrama, tuphlodrama, morodrama, typhlodrama and melodrama. And finally, there is the spectrum of reality and unreality underlying all - such being essential to our theory of dramatic types explored here and here.

Here is mode. The top line, made up of two parts, symbolises the objective and subjective approaches to imitation. Such is a central element of our impressionistic theory found here. The second line represents those major elements of impressionistic theory: realism, impressionism, expressionism and surrealism. Finally, we have a manifestation of the reality quotient of drama as the four major cinematic modes/forms: narrative, avant-garde, animation, documentary.

This is the logic or rules of a cinematic space. The top line represents medial tools; everything from performance to music to writing to lighting, camera work, etc. The central fractured line represents a theory of narrative centres. I have explored 8 major narrative centres of a script, but there are countless more centres of narrative and cinema. The bottom line is the 'reality suppressant'. We have not explored this idea yet, but it is related to a work's place in society and history and so accounts for the ways in which cultural and temporal contextual details confine and define the art.

We come, lastly, to style. Represented here with the top line is a concept of the auteur and so an individual (or a collectively singular) dictative force which gives a work certain personality. In the centre is an infinitely fractured line representative of genres: that quality of art that connects it to other arts. Finally, we have represented our theory of a fundamental structure and space that is bent by narrative.

We are now nearing the end of our brisk exploration. The final element of the cinematic taijitu that must be recognised is the cyclic function, and its commentary on the relation between the 7 elements explored.

Consciousness is a construct that necessitates a medium of art. Simultaneously, it requires style: preceding works. As said, far more often than not, one moves into a medium as to express another personal style in conjuncture to their own unconscious identity. We see this kind of relationship all around the taijitu. Mode, for example, requires the pre-existence of drama in the cinematic space before beginning to shape a story, which, itself, necessitates the construction of rules or the founding of logic.

Finally, this cyclical function suggests that art is created when the taijitu revolves clockwise, when unconsciousness chases Tao and consciousness becomes medium, becomes trichotomy, becomes drama, etc:

Art is understood and experienced, however, when unconsciousness stops chasing Tao and becomes receptive and passive.

This occurs when one actively feels and analyses a film. In this practice, style can be understood as derivative of logic, of mode,of drama, the trichotomy, medium, consciousness and, possibly, unconsciousness that imitates Tao.

Much more could be explored in this theory. But, I will end abruptly now having outlined all of its major elements. Thank you for reading.

Previous post:

End Of The Week Shorts #82

Next post:

Weekend At Mafeteng - Positive

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

An expansion of our theory of the cinematic space that attempts to answer a question of how cinema works.

We recently proposed a system of ideas that answered the question, How does cinema work? Our answer concerned a theory of the cinematic space and so dealt with the literal functioning of cinema as drama moves narrative. Due to its depth, the presented theory lacked certain details that I have since been working on and would like to use to expand our answer beyond dramatic narrative and to a totality of cinema. I would thus like to introduce this:

Inspired loosely by Taoist thought and the designs of Chinese philosophical icons found in places such as the I Ching, I have used the taijitu or bagua as an aesthetic, formal foundation for organising my ideas. What is fundamentally presented here is an up and a down, a give and a take that revolve around one another, grow and shrink respectively and in synchrony. This is the symbol of the taijitu, known as yin-yang. In addition to this is are surrounding blocks. These bear no relation to the hexagrams found in the I Ching. The hexagrams, a source of great complexity and, as some may know, Taoist divination, only inspire my relation of a core cycle to a larger cycle in cinema. Alas, though the above diagram is essential to our theory, we will start with a simpler diagram demonstrating the two key functional cycles in cinema:

These two diagrams are almost one and the same--the cinematic taijitu is merely more complex and expansive. What you will notice, however, is what I have presented here are the major elements of the cinematic space: 0, (, | | and S. We have explored these elements and their functioning before:

What we are to explore today are not going to be altogether new ideas. The step I would like to take today is integrative, and so concerns the combination of our many disparate ideas concerning the objective, subjective, concerning drama, concerning genre, mode, truth and more. We will only need to explore two key frameworks as to do this. Firstly, a theory of mimesis.

Our conception of mimesis, which is made up of known and known imitation, is one that means to take us through the Jungian depths of the mind and out into an abstract cosmological space one may equate to Tao. Consciousness, to Jung, is the highest manifestation of a reality principal in the human psyche; it is that which recognises the world and can simultaneously be accessed by the self and psyche. Consciousness deals with that which we know and know we know. Underneath this is a subconsciousness, what Jung would term the personal unconscious. This is a space of great impact, but, despite its deep foundations in the psyche and profound effect on conception, it often deals with reality in ways unknown to the self. Thus it is a place of the mind that interacts with the known in an unknown capacity. Below this is a deeper, darker unconsciousness which Jung terms the collective unconscious. This confronts the unknown elements of the universe, operating almost entirely unseen if not for the manifestation of symbolism, narrative and things alike in culture. The deepest depths of unconsciousness is too real to be human, so real that it becomes nature. Thus, it is a product of and imitative of the principals of fundamental reality in the universe around us - that which has been termed Tao in Chinese philosophy. Tao is unknowable and unknown, but the essence of consciousness itself.

Our exposition here is not necessarily psychological, psychoanalytical or philosophical. This is an ontology of art and narrative that Aristotle, albeit shakily, projects with his term mimesis. 'Mimesis' implies that, what manifests at the highest levels of tangibility and conception has foundations deeper than what is apparent; that what is is only so because it emerges from something that was, something that has always been. In narrative terms, what is consciously conceived and seen in art is then a product of subconsciousness, that a product of a collective unconsciousness, that an imitation of the essential reality, the absolute truths, of the universe. Such is a kind of logic followed by romantic theorist Friedrich von Schelling when he, in his book System of Transcendental Idealism, says:

The work of art reflects for us the identity of conscious and unconscious activity. But the opposite of the two is infinite, and it is overcome without any contribution of freedom. The basic character of the work of art is thus an unconscious infinity (synthesis of nature and freedom).

What Schelling conceptualises as an 'unconscious infinity' underlying art and the human psyche, we conceptualise as Tao. It is not difficult to arrive at conclusions such as these for, one could argue, embedded in any theological structure figure-headed by a deity or supreme, creationary force is the fundamental assertion that what is is a manifestation of what was and that such has always been. We see this, too, in science. How, after all, can truth be measured if not with the assumption that truth exists and always has; that what can be presently measured is an indication of the histroical foundations of reality if understood wholly? Our hierarchy is nothing of a revelation, it is simply a basic distillation of uncomplicated logic that we can simplify as such:

Whilst Jung always struggled to suggest, sometimes neglected entirely, where the collective unconscious emerged from, what his archetypes that make up this realm were imitative of, we can make a simple extrapolation from his work and put his conception of fundamental, collective unconsciousness in a cycle with Tao.

Here we see represented Tao (.) and unconsciousness (\). Whilst each level of the human psyche, its collective and personal unconscious and consciousness, interacts, formulating a spectrum of awakeness, there is a fundamental disconnect between the human body and nature. This can only be overcome via illusion and imitation: humanity integrating back into nature. Thus, the fundamental truth in reality can be seen to inform and be chased by the human psyche. This is why Tao and unconsciousness cycle one another. Such can be more profoundly demonstrated with reference to the taijitu:

The taijitu does not represent the basic idea of yin and yang that many hold. Far beyond dark and light, good and bad, yin and yang are fractions of Tao, and are thus unnameable, which is to say, they cannot be given a satisfactory, all-encompassing definition. Terms associated with yin, however, are darkness, negativity and passivity. In contrast, yang is light, positivity and activity. As implied, these two entities are not opposites despite being different. As fractions of Tao they are complementary, wholly existent together. The simplest way to then think of yin and yang is in terms of night and day. It is not that night and day oppose one another, but that day gives way to night, night gives way to day, that they cause and infer each other, one result of ten thousand being the human sleep cycle: we rest so that we can work, we work so that we can rest; we follow this cycle as to align ourselves with a higher ideal (maybe Tao). One can then associate yin with anything absorbative and passive and yang with anything expressive and active. This, indeed, is a foundational element of Taoist divination demonstrated by the I Ching. We can do this ourselves by associating yin, negativity, with Tao and unconsciousness with yang, positivity. For, in all mimetic endeavours, the unconsciousness is actively attempting to penetrate fundamental reason and truth, to somehow glean from the infinite and absolute. This infinite and absolute, Tao, is illusive and so it evades, it shrinks as unconsciousness grows, grows as unconsciousness shrinks, circles as the other circles. Alas, in the unconsciousness are markers of the ultimate nature (after all, unconsciousness is human nature). Likewise, in the ultimate nature, that which birthed humanity, is human nature. This dark is in light and light in dark; this is why they inherently chase one another.

This is the essential representation of mimetic investigation: human nature dances with absolute nature and consciousness tries to listen to their music.

Having understood this primary element of our theory, we can move onto an art-centric manifestation:

Here we have a hierarchical breakdown of a functioning art. The diagram may be easily followed, but let us delve into it.

Whilst the incentive for art may arise from unconsciousness, from the universe itself, the first concrete step of art's creation is a conscious decision. This decision leads to the founding of a medium. For example, if the first caveman wants to draw, he will have to found the medium of painting to do this. In founding this medium, however, the caveman immediately initiates a trichotomy, an objective-subjective construct between an artist, an audience and a medial object. We have explored this concept before thusly:

Art is a manifestation of these three entities. For cinema, the subjective entity is an audience, a spectator of sorts. The objective entity is the screen and the technical constructs that the cinematic medium requires: as said, a screen, but also a camera, sound system, a set, actors, a script, etc. Presiding over these two, both objective and subjective, is the filmmaker. This is the basic trichotomy.

This trichotomy leads to the construction of an artistic space. We shall concern ourselves with the cinematic space. And, as we have explored many times over, the cinematic space is made up of four entities: drama, most foundationally, then mode, then logic and then style.

It is unnecessary for us to go into detail here as have done so before. We can, however, reduce our hierarchy to its basic symbols:

Now we understand this formulation, it must be highlighted that style connotes genre and that which associates one expression of a medium to multiple orders of others (expressions made by the same artist, those from a similar period, a singular movement, a sub-genre, genre, form, mode, etc). The style of a work can be thought of as that which binds directly to the conscious element of art. This implies a cycle.

Both cyclical and hierarchical, art is a movement between conscious intention and conscious re-invention. The first art work was a manifestation of consciousness meant to unite an artist, audience and medial object that was itself a construct of drama, mode, logic and style. The second work to manifest, however, would not just be a conscious construct, but a construct conscious of the art work that preceded it. Thus, embedded in any conscious decision to move into a medium and create a work is the soul of the endless works before it. Such is a key assertion of structuralist theory, and can is expressed by a figure such as Northrop Frye in his Anatomy of Criticism:

Poems can only be made out of other poems; novels out of novels. Literature shapes itself and is not shaped externally...

It is clear that I am not in complete agreement with Frye as he refuses to move out of a classically structuralist realm of the artistic space (that which I deal with only with drama, mode, logic and style). Alas, he shines light on the link between created works and the process of creating new works, between style (genre) and consciousness.

Having understood that art is a mimetic function predicated on a cycle between unconsciousness and the essence of nature and that it manifests as a movement between conscious creation and recreation, we can arrive at a dual cycle that reveals a more cohesive picture of what an art, cinema, is and how it functions.

The major revelation in the combination of these two cycles concerns a formalisation of originality or individuality in artistic creation. It is not that literature creates literature, as Frye asserts, but that literature follows literature and simultaneously is created, always, out of consciousness that has its ear to the bedrock of unconsciousness and therefore can express truth in nature - that which may not be found in preceding literature. This is not to suggest that essential, absolute truth is stumbled upon by every individual piece of work, just that there is always the potential for a new resonance between human and reality.

Our final task now is to briefly expand upon the seven major elements bordering the central cycle of cinema. We can then explore the most complex manifestation of all we have so far spoken of with this:

As you should be able to recognise, this is a direct manifestation of the previous dual cycle and so each component has a character we have spoken of before. Let us make this obvious with annotation:

Rather simply, consciousness is made up of the Jungian tripartite: consciousness, personal unconscious and collective unconscious - a trichotomy I usually reduce to consciousness, subconsciousness and unconsciousness. It is only important to note here that unconsciousness, the bottom entity, is not fully represented. It is present here as an entity connecting this conscious element down to the unconsciousness that circulates Tao.

Next, we have medium. I have represented this simply with two blocks together symbolising a definition of medium to be technological expression. I then assert with this that any given medium is a determination of expression - for example, cinema wants images to move - and technology - to make images move, the cinematic camera had to be invented. Medium is an abstract concept, but all mediums may be differentiated on the grounds of both technology and expression, indeed, this is how we define and categorise them. Sculpture means to express life with tools such as chisels and media such as stone; painting, too means to capture life, its chosen tools are a canvas, a brush and paint; theatre has its expressive yearnings and uses the performing body and script to do so. Expression unites all mediums, technology differentiates them and informs the typology of expression.

Here we have represented the tripartite. We have discussed these elements already: the object, the subject, the mediator; the medial devices, the spectator, the artist; a screen, an audience, a filmmaker.

Here is drama. It is represented through three lines. The top line, split into two parts, symbolises the known and unknown mimetic functions explored here. In addition to this are the five types of drama: biodrama, tuphlodrama, morodrama, typhlodrama and melodrama. And finally, there is the spectrum of reality and unreality underlying all - such being essential to our theory of dramatic types explored here and here.

Here is mode. The top line, made up of two parts, symbolises the objective and subjective approaches to imitation. Such is a central element of our impressionistic theory found here. The second line represents those major elements of impressionistic theory: realism, impressionism, expressionism and surrealism. Finally, we have a manifestation of the reality quotient of drama as the four major cinematic modes/forms: narrative, avant-garde, animation, documentary.

This is the logic or rules of a cinematic space. The top line represents medial tools; everything from performance to music to writing to lighting, camera work, etc. The central fractured line represents a theory of narrative centres. I have explored 8 major narrative centres of a script, but there are countless more centres of narrative and cinema. The bottom line is the 'reality suppressant'. We have not explored this idea yet, but it is related to a work's place in society and history and so accounts for the ways in which cultural and temporal contextual details confine and define the art.

Consciousness is a construct that necessitates a medium of art. Simultaneously, it requires style: preceding works. As said, far more often than not, one moves into a medium as to express another personal style in conjuncture to their own unconscious identity. We see this kind of relationship all around the taijitu. Mode, for example, requires the pre-existence of drama in the cinematic space before beginning to shape a story, which, itself, necessitates the construction of rules or the founding of logic.

Finally, this cyclical function suggests that art is created when the taijitu revolves clockwise, when unconsciousness chases Tao and consciousness becomes medium, becomes trichotomy, becomes drama, etc:

Art is understood and experienced, however, when unconsciousness stops chasing Tao and becomes receptive and passive.

This occurs when one actively feels and analyses a film. In this practice, style can be understood as derivative of logic, of mode,of drama, the trichotomy, medium, consciousness and, possibly, unconsciousness that imitates Tao.

Much more could be explored in this theory. But, I will end abruptly now having outlined all of its major elements. Thank you for reading.

Previous post:

End Of The Week Shorts #82

Next post:

Weekend At Mafeteng - Positive

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack