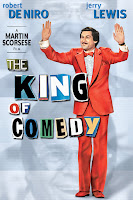

The King Of Comedy - Corrupt Celebrity

Thoughts On: The King Of Comedy (1982)

Rupert Pupkin will be the next big thing in comedy... whatever it takes.

The King Of Comedy has got to be one of Scorsese's most overlooked pictures, but is nonetheless often regarded as one of his best by those who have seen it. This then seems to have remained, to an extent, in the position it was in when it first came out; a bomb at the box office despite critical acclaim. Nonetheless, The King Of Comedy is truly brilliant.

If we were to start with the negatives, I feel there is only one place to point: Sandra Bernhard as the psychotic fanatic who seemingly wants Jerry Lewis' Jerry Langford to be both a lover and a replacement of her father. Whilst Bernhard's performance isn't bad, the manner in which her character is written and played is a little too loud and simple to contest with De Niro as Rupert Pupkin. As a result, Masha is indeed a weak point of the movie that sometimes gets on your nerves for the wrong reasons.

The subtle weight on this film that I believe may be part of why it is a relatively obscure and unsuccessful Scorsese picture concerns its themes of fame, stardom, celebrity and idolisation. Criticising the culture around celebrity is incredibly easy, and though Scorsese voices his concerns brilliantly, this remains a difficult subject to tackle.

The mantra and philosophy of this blog is "If it affects you, it means something". As clunky as this is, I find it to be something that I am constantly returning to. After all, all that we do on this blog concerns taking the material of a film that affects us and trying to understand what it is and why it has an effect. This, in my opinion, is a core purpose of all arts and science; to treat yourself and the world around you seriously, you must investigate sparks in the darkness. These sparks for the physicist, for example, may be the universal pull that keeps us on earth. Investigation of the affect/effect of this pull on the human body and its world lead us to the theory of gravity. Though science turns from curiosity (affection) to the study of the objective world (effects), art often deals with affection alone; it is criticism, theory and analysis that study effects. After all, what science cannot answer fully, art usually tries to confront, and what spectatorship cannot articulate, analysis usually tries to grapple. But, whilst "If it affects you, it means something" may be a strong idea, there is a tension within it, and it is realising this that we can break down why The King Of Comedy's critique of celebrity may not be popular.

The philosophy of this blog essentially boils down to an idea that personal experience has meaning. However, how correct is this assumption? Does everything we feel, does everything that affects us, mean something? In my opinion, certainly. Nonetheless, there is a hierarchy of meaning with certain emotions being more trivial or less meaningful than others. The question we then come upon is, how do we distinguish what meanings matter? Moreover, how are you supposed to tell someone that their feelings are meaningless?

This is the issue that The King Of Comedy both presents and embodies. In such, with its critique of celebrity, The King Of Comedy is clearly saying that there is an insanity in a culture, and more so in individuals like Pupkin, that view celebrities as gods walking within a magical box; a magic box which captures a literal--though contrived and fake--heaven on earth. At the same time, though Pupkin's emotions and the meaning he finds in the idea of celebrity are shown to be tragic by this film, we aren't all Pupkin. So, to some degree, in criticising celebrity, Scorsese criticises the affinity people hold for T.V shows and personalities; he takes what affects most people and, again, to some degree, shows it to be meaningless. So, just as much as my saying that "I actually don't watch T.V/T.V shows" would immediately characterise me as pretentious to a lot of people, people don't like to hear the same old shit about T.V being fake and it melting minds away.

There are clear limitations to the critique of celebrity implied through the contempt and judgement you will often be met with when voicing such opinions. Though some may use this to suggest that most people are just dumb - you can imagine the likes of George Carlin suggesting this - there is more to the dismissal of this discord. Interestingly, there are many parallels (which have been drawn countless times before now) between celebrity and religion. What I find even more intriguing, however, is that there are also parallels to be seen in the way in which celebrity and religion are critiqued. As becomes quite clear in The King Of Comedy, celebrities are almost like gods that the masses worship and imitate. This is a rather basic analysis. However, just as many people describe this celebrity worship as childish and corrupt, so do others characterise religion in the same way.

There is, of course, a huge difference between celebrity and religion. However, the function of both entities is similar. Religion affects people - it gives them answers and structure - and so they search for the meaning and truth it holds. Celebrities affects people, and there is often a search for meaning among the celebrities held in highest regard. Let us consider an example; Muhammad Ali, though he was paid to throw his bones into other mens' faces for our pleasure, also stood for much more in regards to peace and unity among minorities - the same can be said, to a lesser degree, for figures such as Bruce Lee. Muhammad Ali had his ties to religion and so would likely reject any suggestion that he was a literal prophet of anything other than a whopping in a ring. Nonetheless, Ali seems to have been revered, despised, followed and chastised like prophets and saints in various religious stories are. And though Ali is one of the most respected celebrities, maybe so much so that he is often considered to transcend the label of mere celebrity, lesser celebrities are treated with a similar regard. Consider, for instance, the likes of the Kardashians. As much as they are dismissed as meaningless nonsense, they are hugely popular, influential and even respected for what they have achieved and how they have achieved it in a business sense. Celebrities all walk the hero's path, and with their success comes a status that cannot be refuted; just consider the way in which they affect the masses.

Because the hero is a figure of meaning, celebrities, as ridiculous as they all may be, hold something of meaning whether they like it or not. They may not be religious figures, but, they are a modern day rival, most of which (actors) are figures of storytelling. In fact, celebrities could arguably be an improvement on old heroes as they are recognised as, and interacted with as, both human and idol. There is then always a possible (inevitable maybe) fall from grace with celebrities, and thus the meaning that they embody is shown to be fragile - as all meaning is. So, though the idea of celebrity has its problems, there seems to be a mechanism built into it that preserves the culture around via an embrace of a celebrities faults and, in a strange way, their humanity. Where religion then arguably fails - it can often lack openness to interpretation and critique - celebrity then seemingly prevails. Though, where celebrity fails - it often lacks truly deep and lasting meaning - religion often prevails.

It is viewing the topic at hand in such a way that may enable us to understand exactly why you must be careful in criticising celebrity; the phenomena is not as simple, nor as meaningless, as we'd like to think - and the same can be said for religion. Because of this, we can then understand that: The King Of Comedy isn't as popular as, for example, Goodfellas because it critiques the hero's journey; its subject matter is so difficult to digest, or not very attractive, because it subverts and even undermines what affects us in celebrity and the meaning that may carry; and maybe we can even understand that The King Of Comedy's narrative falls short in places where celebrity is dealt with too simply. However, though I could concede that there is a small percentage of this film that merely criticises and shows little care for understanding celebrity, it does have another side, a side that distinguishes the narrative commentary from basic analysis.

With celebrities as not just pseudo gods, but human idols of worship, Scorsese explores nihilism quite like he does in Taxi Driver within The King Of Comedy. As a result, Jerry Langford is often little more than a signifier that Pupkin is empty and desperate inside. What's more, it is Pupkin's unhealthy relationship with Jerry that is the basis of the film's commentary as Pupkin essentially uses the idea and presence of celebrity not to go on a hero's journey himself, but to avoid it. What The King Of Comedy then has us really ponder is the negative differences between celebrities and gods. Whilst there is a humanity and truth in celebrities being real, fallible humans, becoming a celebrity so often sees a person dehumanised. Jerry Langford, for example, becomes a shell which the average person projects their self into; when people meet him, they speak to him not as a stranger, but a figure they feel they know well. And when Langford doesn't meet expectations, people so often lash out at him. The core problem that Scorsese then raises with the idea of celebrities as 'gods' is that real gods cannot, and never really are, kidnapped and tied up in apartments by mere mortals.

It is this key tension between humanisation and distance that sets the celebrity apart from the god, and leaves them so vulnerable to abuse. And this abuse does not just concern the specific dehumanisation of a celebrity, rather, it is a symptom of a diseased culture. When respect for, and interest in, a celebrity turns into obsession as with Pupkin, we see the celebrity's humanity exploited to the detriment of the obsessor. As said, Langford, much like comedy, then signifies all that is broken within Pupkin; he had a terrible childhood and wants to use comedy to mask this - he wants to become a revered fool. However, the only way that Pupkin can conceive of reaching this position, of becoming the hero of his own narrative, is through arrogance; he isn't willing to be a true fool and walk the path to earn a right of passage, he only wants the easy way. And this leaves us with the iconic ending. Does Pupkin really become famous? Did his set go well? Or, did he imagine it all?

I don't think any of these questions really matter. If Pupkin only imagines that he finds success, then he has deluded himself to the nth degree; he has not changed and has instead sunk into his own emptiness. If Pupkin actually is successful, however, then does this not reflect that there are many others like him out in the world, those who will not just worship celebrities, but see their fallible humanity before dehumanising them, reducing them to a shell to revere for the sake of exploitation?

The end of The King Of Comedy is a powerful one because it essentially asks us if the negatives of celebrity culture reside within Pupkin alone, or within us all. With all of what we have talked about today in mind, I then leave you with this question: Who is the corrupted in The King Of Comedy?

Previous post:

Kukurantumi, Road To Accra - The Futile Road?

Next post:

Get Out - What Could 'Get Out 2' Look Like?

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

Rupert Pupkin will be the next big thing in comedy... whatever it takes.

The King Of Comedy has got to be one of Scorsese's most overlooked pictures, but is nonetheless often regarded as one of his best by those who have seen it. This then seems to have remained, to an extent, in the position it was in when it first came out; a bomb at the box office despite critical acclaim. Nonetheless, The King Of Comedy is truly brilliant.

If we were to start with the negatives, I feel there is only one place to point: Sandra Bernhard as the psychotic fanatic who seemingly wants Jerry Lewis' Jerry Langford to be both a lover and a replacement of her father. Whilst Bernhard's performance isn't bad, the manner in which her character is written and played is a little too loud and simple to contest with De Niro as Rupert Pupkin. As a result, Masha is indeed a weak point of the movie that sometimes gets on your nerves for the wrong reasons.

The subtle weight on this film that I believe may be part of why it is a relatively obscure and unsuccessful Scorsese picture concerns its themes of fame, stardom, celebrity and idolisation. Criticising the culture around celebrity is incredibly easy, and though Scorsese voices his concerns brilliantly, this remains a difficult subject to tackle.

The mantra and philosophy of this blog is "If it affects you, it means something". As clunky as this is, I find it to be something that I am constantly returning to. After all, all that we do on this blog concerns taking the material of a film that affects us and trying to understand what it is and why it has an effect. This, in my opinion, is a core purpose of all arts and science; to treat yourself and the world around you seriously, you must investigate sparks in the darkness. These sparks for the physicist, for example, may be the universal pull that keeps us on earth. Investigation of the affect/effect of this pull on the human body and its world lead us to the theory of gravity. Though science turns from curiosity (affection) to the study of the objective world (effects), art often deals with affection alone; it is criticism, theory and analysis that study effects. After all, what science cannot answer fully, art usually tries to confront, and what spectatorship cannot articulate, analysis usually tries to grapple. But, whilst "If it affects you, it means something" may be a strong idea, there is a tension within it, and it is realising this that we can break down why The King Of Comedy's critique of celebrity may not be popular.

The philosophy of this blog essentially boils down to an idea that personal experience has meaning. However, how correct is this assumption? Does everything we feel, does everything that affects us, mean something? In my opinion, certainly. Nonetheless, there is a hierarchy of meaning with certain emotions being more trivial or less meaningful than others. The question we then come upon is, how do we distinguish what meanings matter? Moreover, how are you supposed to tell someone that their feelings are meaningless?

This is the issue that The King Of Comedy both presents and embodies. In such, with its critique of celebrity, The King Of Comedy is clearly saying that there is an insanity in a culture, and more so in individuals like Pupkin, that view celebrities as gods walking within a magical box; a magic box which captures a literal--though contrived and fake--heaven on earth. At the same time, though Pupkin's emotions and the meaning he finds in the idea of celebrity are shown to be tragic by this film, we aren't all Pupkin. So, to some degree, in criticising celebrity, Scorsese criticises the affinity people hold for T.V shows and personalities; he takes what affects most people and, again, to some degree, shows it to be meaningless. So, just as much as my saying that "I actually don't watch T.V/T.V shows" would immediately characterise me as pretentious to a lot of people, people don't like to hear the same old shit about T.V being fake and it melting minds away.

There are clear limitations to the critique of celebrity implied through the contempt and judgement you will often be met with when voicing such opinions. Though some may use this to suggest that most people are just dumb - you can imagine the likes of George Carlin suggesting this - there is more to the dismissal of this discord. Interestingly, there are many parallels (which have been drawn countless times before now) between celebrity and religion. What I find even more intriguing, however, is that there are also parallels to be seen in the way in which celebrity and religion are critiqued. As becomes quite clear in The King Of Comedy, celebrities are almost like gods that the masses worship and imitate. This is a rather basic analysis. However, just as many people describe this celebrity worship as childish and corrupt, so do others characterise religion in the same way.

There is, of course, a huge difference between celebrity and religion. However, the function of both entities is similar. Religion affects people - it gives them answers and structure - and so they search for the meaning and truth it holds. Celebrities affects people, and there is often a search for meaning among the celebrities held in highest regard. Let us consider an example; Muhammad Ali, though he was paid to throw his bones into other mens' faces for our pleasure, also stood for much more in regards to peace and unity among minorities - the same can be said, to a lesser degree, for figures such as Bruce Lee. Muhammad Ali had his ties to religion and so would likely reject any suggestion that he was a literal prophet of anything other than a whopping in a ring. Nonetheless, Ali seems to have been revered, despised, followed and chastised like prophets and saints in various religious stories are. And though Ali is one of the most respected celebrities, maybe so much so that he is often considered to transcend the label of mere celebrity, lesser celebrities are treated with a similar regard. Consider, for instance, the likes of the Kardashians. As much as they are dismissed as meaningless nonsense, they are hugely popular, influential and even respected for what they have achieved and how they have achieved it in a business sense. Celebrities all walk the hero's path, and with their success comes a status that cannot be refuted; just consider the way in which they affect the masses.

Because the hero is a figure of meaning, celebrities, as ridiculous as they all may be, hold something of meaning whether they like it or not. They may not be religious figures, but, they are a modern day rival, most of which (actors) are figures of storytelling. In fact, celebrities could arguably be an improvement on old heroes as they are recognised as, and interacted with as, both human and idol. There is then always a possible (inevitable maybe) fall from grace with celebrities, and thus the meaning that they embody is shown to be fragile - as all meaning is. So, though the idea of celebrity has its problems, there seems to be a mechanism built into it that preserves the culture around via an embrace of a celebrities faults and, in a strange way, their humanity. Where religion then arguably fails - it can often lack openness to interpretation and critique - celebrity then seemingly prevails. Though, where celebrity fails - it often lacks truly deep and lasting meaning - religion often prevails.

It is viewing the topic at hand in such a way that may enable us to understand exactly why you must be careful in criticising celebrity; the phenomena is not as simple, nor as meaningless, as we'd like to think - and the same can be said for religion. Because of this, we can then understand that: The King Of Comedy isn't as popular as, for example, Goodfellas because it critiques the hero's journey; its subject matter is so difficult to digest, or not very attractive, because it subverts and even undermines what affects us in celebrity and the meaning that may carry; and maybe we can even understand that The King Of Comedy's narrative falls short in places where celebrity is dealt with too simply. However, though I could concede that there is a small percentage of this film that merely criticises and shows little care for understanding celebrity, it does have another side, a side that distinguishes the narrative commentary from basic analysis.

With celebrities as not just pseudo gods, but human idols of worship, Scorsese explores nihilism quite like he does in Taxi Driver within The King Of Comedy. As a result, Jerry Langford is often little more than a signifier that Pupkin is empty and desperate inside. What's more, it is Pupkin's unhealthy relationship with Jerry that is the basis of the film's commentary as Pupkin essentially uses the idea and presence of celebrity not to go on a hero's journey himself, but to avoid it. What The King Of Comedy then has us really ponder is the negative differences between celebrities and gods. Whilst there is a humanity and truth in celebrities being real, fallible humans, becoming a celebrity so often sees a person dehumanised. Jerry Langford, for example, becomes a shell which the average person projects their self into; when people meet him, they speak to him not as a stranger, but a figure they feel they know well. And when Langford doesn't meet expectations, people so often lash out at him. The core problem that Scorsese then raises with the idea of celebrities as 'gods' is that real gods cannot, and never really are, kidnapped and tied up in apartments by mere mortals.

It is this key tension between humanisation and distance that sets the celebrity apart from the god, and leaves them so vulnerable to abuse. And this abuse does not just concern the specific dehumanisation of a celebrity, rather, it is a symptom of a diseased culture. When respect for, and interest in, a celebrity turns into obsession as with Pupkin, we see the celebrity's humanity exploited to the detriment of the obsessor. As said, Langford, much like comedy, then signifies all that is broken within Pupkin; he had a terrible childhood and wants to use comedy to mask this - he wants to become a revered fool. However, the only way that Pupkin can conceive of reaching this position, of becoming the hero of his own narrative, is through arrogance; he isn't willing to be a true fool and walk the path to earn a right of passage, he only wants the easy way. And this leaves us with the iconic ending. Does Pupkin really become famous? Did his set go well? Or, did he imagine it all?

I don't think any of these questions really matter. If Pupkin only imagines that he finds success, then he has deluded himself to the nth degree; he has not changed and has instead sunk into his own emptiness. If Pupkin actually is successful, however, then does this not reflect that there are many others like him out in the world, those who will not just worship celebrities, but see their fallible humanity before dehumanising them, reducing them to a shell to revere for the sake of exploitation?

The end of The King Of Comedy is a powerful one because it essentially asks us if the negatives of celebrity culture reside within Pupkin alone, or within us all. With all of what we have talked about today in mind, I then leave you with this question: Who is the corrupted in The King Of Comedy?

Previous post:

Kukurantumi, Road To Accra - The Futile Road?

Next post:

Get Out - What Could 'Get Out 2' Look Like?

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack