Every Year In Film #15 - Falling Cat

Thoughts On: Falling Cat (1894)

A cat, held upside down, is dropped, turning as it descends to land on its feet. In other worlds, a cat falls.

Étienne-Jules Marey is an incredibly significant artist and scientist who developed remarkable photographic and cinematic technology, as well as sensibilities, in the 'pre-cinema' era. We have made allusions to Marey ever since the Every Year series began, but haven't yet had the chance to talk specifically about him. It now seems that there couldn't be a better time to talk about Marey as we will next be exploring 1895 and, as you may guess, the Lumières.

Over the past dozen or so posts, we have looked at many technological innovations, like the use of film strips, perforated celluloid and single lens cameras. What's more we have discussed the commercialisation of 'cinema', which was arguably founded with Edison, as well as identified the roots of an early cinematic aesthetic through Louis Le Prince. However, the first major idea from the pre-filmic era that we established through the Every Year series was connected to Muybridge. Muybridge, as one of the first directors of 'cinema', showed a focus on the philosophical implications and the reasons for the form like few did after him; many like Greene, Dickson, Edison and Demenÿ only really demonstrated a focus on entertainment, technology and commercialisation. We then only have 3 particularly interesting and significant figures that emerged from the late 1870s, 1880s and early 1890s. Firstly, as mentioned, is Muybridge.

Muybridge, in my view, represents control and a person harnessing time itself for personal, for lack of a better word, satisfaction. Second to him, we have Reynaud, who made some of the largest leaps towards what we know as cinema today with his animated films, projected with the use of perforated celluloid.

Whilst Reynaud does represent technological innovation, underlying the evolution of his apparatus was a yearning to tell stories. This is why he invented longer film strips and his Optical Theatre. Reynaud was then incredibly significant as he was the first person who used cinema to tell stories and who brought life and motion to the magic lantern presentations of even earlier pre-cinematic days.

Thirdly is the figure we mean to explore today: Marey. When we discuss the profound implications of Muybridge's work, there comes a point at which we have to pull on the reigns of our enthusiasm. This is because Muybridge wasn't really a strict scientist - despite his claims and formal choices that begin to imply such a facade. Because Muybridge was not using cinema scientifically, we cannot easily see that he truly cared for the study of motion, space and time; instead, it is quite clear that he revered the power of such a control and captured that aesthetically - which is what we ourselves (most probably) marvel at too. Marey was a scientist and he had a very clear fascination with space, time and motion. This is what makes his works so significant and the world of his art so awe-inspiring - and quite possibly more so than the work produced by filmmakers for decades to come. But, before exploring this idea, we must first know of Marey himself and then his work.

Born and raised in eastern France, Marey would move north to Paris at age 19 to study physiology and surgery, qualifying as a doctor 10 years later in 1859. There isn't much that is heavily and widely documented about Marey's early life and so we can assume that he lived a rather anonymous life until 1868 when he published his first work studying blood circulation. It's with his paper Le Mouvement dans les fonctions de la vie that Marey's interest with motion is fully established, an interest that of course has roots in physiology. Physiology is, in certain senses, biology in motion; it is the study of processes and bodily functions as attached to time. What we will grow to see is that Marey's 'cinema' is precisely this; it is a study of the body's relationship with time. This is an idea that would later be understood by the Russian auteur, Tarkovsky, as 'Sculpting In Time'. However, whilst Tarkovsky studies time in relation to the existential human soul, Marey established a cinema that was bound to a study of the physical human body.

Marey wouldn't begin to build this cinema, however, until the 1890s. His focus on time's relationship with organisms' bodies for the time being, in the 1860s, was on the measurement of pulses and blood circulation. He would then work with a physiologist, Auguste Chauveau, and a watch manufacturing company, Breguet, to produce a portable sphygmograph, a device that would measure a person's pulse.

He would carry out further studies with this device among others like it (polygraphs, dromographs and other myographs) on various animals with some focus on insects and horses. His research and findings would be published in 1873 within the book, La Machine Animale.

It is in this book, whilst studying the movement of horses, that Marey would suggest that all four of a horse's hooves were off the ground at one point as it gallops. This caught the interest of Leland Stanford and lead to his wager that resulted in a certain photographer called Eadweard Muybridge being called upon to somehow prove this notion to be true. This of course lead to the first ever experiment with multiple high-speed cameras to produce pictures of movement...

Marey was impressed with Muybridge's 1879 publishings, met him in 1881, and was inspired to begin his own work that utilised photography as opposed to the diagrams and illustrations you will see throughout many of his books.

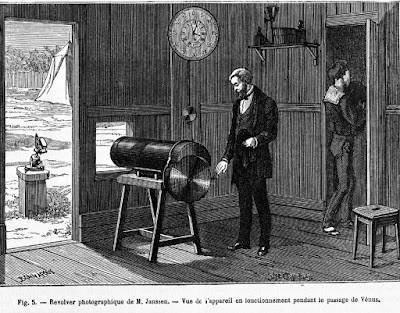

Marey would then look to other figures who had attempted to photograph motion for inspiration and came upon Jules Janssen. You will of course know Janssen from the first film we covered in the Every Year Series: Passage Of Venus. He shot this rare astronomical event with a photographic revolver...

Using metal plate (daguerreotype) photography, Janssen recorded sequential images of Venus passing across the Sun in 1874. The photographic revolver was a huge and cumbersome device and Marey was already dissatisfied to a certain degree with Muybridge's photography as, though it could capture the horse in motion, it couldn't do so well with birds. This meant, despite inspiration, he needed something of his own design.

Marey was interested in flight, which is why he studied insects, creating models of them and later taking breath-taking photographs of insects, birds and marine creatures. So, with the concept of the photographic revolver in mind, Marey invented his chronophotographic gun:

During the 1880s and 90s, Marey spent part of his year in Posillipo, Naples (Italy), and the rest in Paris. It was in Naples that Marey invented this photographic device during 1882. The gun utilised 12 glass plates that would spin as the trigger was pulled, allowing them to be exposed.

Pointing at and 'shooting' birds with this contraption, Marey would have seemed very strange and so was apparently called "The Fool Of Posillipo" by the locals. Nonetheless, Marey would continue with his work, producing images of birds in flight.

Inspired by these studies, he would later have sculptures of birds made in 1887.

He would even patent and produce a 3D zoetrope from these designs, that would function just like their two dimensional counterpart...

However, alongside his work in Naples, Marey would still be working in France. In Paris he was then working with a figure we covered previously, Georges Demenÿ. He worked with Demenÿ in the Station Physiologique, which was constructed in 1882.

Here, he did not continue work with the chronophotographic gun, instead invented a fixed-plate chronophotographic camera that was mounted to rails.

Using this improved device, Marey would take hundreds of pictures from 1882 to 88 with Demenÿ. Their photographs would all capture movement on one plate, establishing the unique aesthetic that many will know Marey for.

On a side-note, if you look at the earlier works of Marey, you will see in his use of graphs a similar aesthetic to this, one of continuous motion:

It then seems that his chronophotographic sensibilities and aesthetic were founded in physical and quantum mechanical wave-like functions, unknowingly bringing to life de Broglie's 1924 proposal that all matter, even people, have a wavelength. However, let's not get too abstract as I may end up wading into water too deep for myself.

In 1888 Marey decided to improve his devices, employing the use of sensitised paper for 2 years as opposed to glass plates. It was in 1890, however, that Marey transitioned from paper to celluloid and began to make, what we would begin to consider, cinema. Initially, Marey would study the human figure in motion (much like Muybridge).

However, Marey quickly distinguished himself from Muybridge who only really shot animals and then people doing various acts semi-naked for many years. In 1891, Marey, in Naples, then began studies on insects:

This is then where Marey really begins to take your breath away. His focus was not simply on a concept of motion, but its details. A great point of comparison between Marey and Muybridge would then be his works from 1893, where he continues to study the human form.

In the examples here, we see exactly what separated Marey from Muybridge: the close-up. It is very rare to see a close-up in the works of Muybridge. His studies were instead on wider motions, in short, acts of motion instead of motion itself:

When we stop to analyse our subject for today we will see that Marey's ethic was centred on our initial idea of physiology and time's relationship with bodies. So, let us introduce Falling Cat...

Whilst there is a novelty in this being the first movie to depict a cat, this was a scientific study that focused on the Cat Righting Reflex. This is an interesting phenomena as it concerns the flexibility of a cat's spine which they innately use to flatten out their bodies when they fall. The reason for this is so that they increase the surface area of their body as they fall so that they can create drag - much like a parachute. Because of this ability and their weight-to-size ratio, cats have a non-fatal terminal velocity. This means that if they are allowed to accelerate to the point at which they stop falling any faster (which is around 60mph) and hit flat land, they are likely to survive. If a cat then falls from over 5 stories high, it has a 90% chance of surviving. However, do not throw your cat off of a tall building. It may not die straight away, but it will likely sustain injuries that it will later die from if not given medical treatment.

With that said, Marey's study of the Cat Righting Reflex demonstrates not just his interest in physiology and bodies, both of humans and animals, which you will find inherent to all of his work, but his interest with time and its relation to organic beings which utilise the physical phenomenon to create motion. This is what makes so much of his work profound; it had reason that implied a whole other purpose that cinema can facilitate. As a result, whilst we may not watch his films as scientific studies, this inherent purpose instills his aesthetics with a focus on the wonders of the physical world.

What Marey then captured with his cinema was, as was suggested at the beginning of the essay, another shade of what would later be Tarkovsky's cinema. Both Tarkovsky and Marey intentionally created Sculptures In Time; whilst Marey had a focus on the physical world, Tarkovsky investigated the existential and subjective realm of the human psyche. It is for this reason that, in 1894, Marey dismissed Demenÿ from his laboratory and replaced him with Lucien Bull - who filmed the incredible short, Ball Passing Through A Soap Bubble, in 1904.

Marey, as we have discussed previously, replaced Demenÿ because he only expressed interest in the commercialisation of chronophotography. Marey was not interested in this side of motion picture photography, instead, the content of his films which scientifically investigated time and the physical world. Coming back to our previous point, the awe that Tarkovsky captures with his films is then certainly captured by Marey's equally pure cinema with everything from his depictions of insects to birds, to people and even sting rays...

... expositing not so much the inner human complex, but the complex beauty of the physical world. Marey, in my opinion, then represents the height of spectacle in the early cinematic period as his spectacle is founded in a scientific intrigue, one that ultimately builds an intellectual and even profound spectacle.

Étienne-Jules Marey would work on his films from 1890 until 1900. Beyond 1900, he worked with smoke, studying gaseous motion.

And later he would work with Lucien Bull on projects like Ball Passing Through A Soap Bubble. However, it was in this year, 1904, that Marey died at aged 74.

Marey's impact on cinema is one that is, very clearly, giant. He not only directly influenced Muybridge, Edison and the Lumières, but he retained an aesthetic and a cinema of his own that no one could replicate. Marey is then a giant above giants in the pre-cinematic and early cinematic eras - one that shouldn't be forgotten as we explore the 'birth of cinema' with the Lumières very soon. I'll then conclude this lengthy look at Marey with a link to a collection of his films for you to further investigate: link here.

Previous post:

Day Of Wrath - What Is A Witch?

Next post:

The Gods Must Be Crazy - Reductionist Film

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

Étienne-Jules Marey is an incredibly significant artist and scientist who developed remarkable photographic and cinematic technology, as well as sensibilities, in the 'pre-cinema' era. We have made allusions to Marey ever since the Every Year series began, but haven't yet had the chance to talk specifically about him. It now seems that there couldn't be a better time to talk about Marey as we will next be exploring 1895 and, as you may guess, the Lumières.

Over the past dozen or so posts, we have looked at many technological innovations, like the use of film strips, perforated celluloid and single lens cameras. What's more we have discussed the commercialisation of 'cinema', which was arguably founded with Edison, as well as identified the roots of an early cinematic aesthetic through Louis Le Prince. However, the first major idea from the pre-filmic era that we established through the Every Year series was connected to Muybridge. Muybridge, as one of the first directors of 'cinema', showed a focus on the philosophical implications and the reasons for the form like few did after him; many like Greene, Dickson, Edison and Demenÿ only really demonstrated a focus on entertainment, technology and commercialisation. We then only have 3 particularly interesting and significant figures that emerged from the late 1870s, 1880s and early 1890s. Firstly, as mentioned, is Muybridge.

Whilst Reynaud does represent technological innovation, underlying the evolution of his apparatus was a yearning to tell stories. This is why he invented longer film strips and his Optical Theatre. Reynaud was then incredibly significant as he was the first person who used cinema to tell stories and who brought life and motion to the magic lantern presentations of even earlier pre-cinematic days.

Thirdly is the figure we mean to explore today: Marey. When we discuss the profound implications of Muybridge's work, there comes a point at which we have to pull on the reigns of our enthusiasm. This is because Muybridge wasn't really a strict scientist - despite his claims and formal choices that begin to imply such a facade. Because Muybridge was not using cinema scientifically, we cannot easily see that he truly cared for the study of motion, space and time; instead, it is quite clear that he revered the power of such a control and captured that aesthetically - which is what we ourselves (most probably) marvel at too. Marey was a scientist and he had a very clear fascination with space, time and motion. This is what makes his works so significant and the world of his art so awe-inspiring - and quite possibly more so than the work produced by filmmakers for decades to come. But, before exploring this idea, we must first know of Marey himself and then his work.

Born and raised in eastern France, Marey would move north to Paris at age 19 to study physiology and surgery, qualifying as a doctor 10 years later in 1859. There isn't much that is heavily and widely documented about Marey's early life and so we can assume that he lived a rather anonymous life until 1868 when he published his first work studying blood circulation. It's with his paper Le Mouvement dans les fonctions de la vie that Marey's interest with motion is fully established, an interest that of course has roots in physiology. Physiology is, in certain senses, biology in motion; it is the study of processes and bodily functions as attached to time. What we will grow to see is that Marey's 'cinema' is precisely this; it is a study of the body's relationship with time. This is an idea that would later be understood by the Russian auteur, Tarkovsky, as 'Sculpting In Time'. However, whilst Tarkovsky studies time in relation to the existential human soul, Marey established a cinema that was bound to a study of the physical human body.

Marey wouldn't begin to build this cinema, however, until the 1890s. His focus on time's relationship with organisms' bodies for the time being, in the 1860s, was on the measurement of pulses and blood circulation. He would then work with a physiologist, Auguste Chauveau, and a watch manufacturing company, Breguet, to produce a portable sphygmograph, a device that would measure a person's pulse.

He would carry out further studies with this device among others like it (polygraphs, dromographs and other myographs) on various animals with some focus on insects and horses. His research and findings would be published in 1873 within the book, La Machine Animale.

It is in this book, whilst studying the movement of horses, that Marey would suggest that all four of a horse's hooves were off the ground at one point as it gallops. This caught the interest of Leland Stanford and lead to his wager that resulted in a certain photographer called Eadweard Muybridge being called upon to somehow prove this notion to be true. This of course lead to the first ever experiment with multiple high-speed cameras to produce pictures of movement...

Marey was impressed with Muybridge's 1879 publishings, met him in 1881, and was inspired to begin his own work that utilised photography as opposed to the diagrams and illustrations you will see throughout many of his books.

Marey would then look to other figures who had attempted to photograph motion for inspiration and came upon Jules Janssen. You will of course know Janssen from the first film we covered in the Every Year Series: Passage Of Venus. He shot this rare astronomical event with a photographic revolver...

Using metal plate (daguerreotype) photography, Janssen recorded sequential images of Venus passing across the Sun in 1874. The photographic revolver was a huge and cumbersome device and Marey was already dissatisfied to a certain degree with Muybridge's photography as, though it could capture the horse in motion, it couldn't do so well with birds. This meant, despite inspiration, he needed something of his own design.

Marey was interested in flight, which is why he studied insects, creating models of them and later taking breath-taking photographs of insects, birds and marine creatures. So, with the concept of the photographic revolver in mind, Marey invented his chronophotographic gun:

During the 1880s and 90s, Marey spent part of his year in Posillipo, Naples (Italy), and the rest in Paris. It was in Naples that Marey invented this photographic device during 1882. The gun utilised 12 glass plates that would spin as the trigger was pulled, allowing them to be exposed.

Pointing at and 'shooting' birds with this contraption, Marey would have seemed very strange and so was apparently called "The Fool Of Posillipo" by the locals. Nonetheless, Marey would continue with his work, producing images of birds in flight.

He would even patent and produce a 3D zoetrope from these designs, that would function just like their two dimensional counterpart...

However, alongside his work in Naples, Marey would still be working in France. In Paris he was then working with a figure we covered previously, Georges Demenÿ. He worked with Demenÿ in the Station Physiologique, which was constructed in 1882.

Here, he did not continue work with the chronophotographic gun, instead invented a fixed-plate chronophotographic camera that was mounted to rails.

Using this improved device, Marey would take hundreds of pictures from 1882 to 88 with Demenÿ. Their photographs would all capture movement on one plate, establishing the unique aesthetic that many will know Marey for.

On a side-note, if you look at the earlier works of Marey, you will see in his use of graphs a similar aesthetic to this, one of continuous motion:

It then seems that his chronophotographic sensibilities and aesthetic were founded in physical and quantum mechanical wave-like functions, unknowingly bringing to life de Broglie's 1924 proposal that all matter, even people, have a wavelength. However, let's not get too abstract as I may end up wading into water too deep for myself.

In 1888 Marey decided to improve his devices, employing the use of sensitised paper for 2 years as opposed to glass plates. It was in 1890, however, that Marey transitioned from paper to celluloid and began to make, what we would begin to consider, cinema. Initially, Marey would study the human figure in motion (much like Muybridge).

However, Marey quickly distinguished himself from Muybridge who only really shot animals and then people doing various acts semi-naked for many years. In 1891, Marey, in Naples, then began studies on insects:

This is then where Marey really begins to take your breath away. His focus was not simply on a concept of motion, but its details. A great point of comparison between Marey and Muybridge would then be his works from 1893, where he continues to study the human form.

In the examples here, we see exactly what separated Marey from Muybridge: the close-up. It is very rare to see a close-up in the works of Muybridge. His studies were instead on wider motions, in short, acts of motion instead of motion itself:

When we stop to analyse our subject for today we will see that Marey's ethic was centred on our initial idea of physiology and time's relationship with bodies. So, let us introduce Falling Cat...

Whilst there is a novelty in this being the first movie to depict a cat, this was a scientific study that focused on the Cat Righting Reflex. This is an interesting phenomena as it concerns the flexibility of a cat's spine which they innately use to flatten out their bodies when they fall. The reason for this is so that they increase the surface area of their body as they fall so that they can create drag - much like a parachute. Because of this ability and their weight-to-size ratio, cats have a non-fatal terminal velocity. This means that if they are allowed to accelerate to the point at which they stop falling any faster (which is around 60mph) and hit flat land, they are likely to survive. If a cat then falls from over 5 stories high, it has a 90% chance of surviving. However, do not throw your cat off of a tall building. It may not die straight away, but it will likely sustain injuries that it will later die from if not given medical treatment.

With that said, Marey's study of the Cat Righting Reflex demonstrates not just his interest in physiology and bodies, both of humans and animals, which you will find inherent to all of his work, but his interest with time and its relation to organic beings which utilise the physical phenomenon to create motion. This is what makes so much of his work profound; it had reason that implied a whole other purpose that cinema can facilitate. As a result, whilst we may not watch his films as scientific studies, this inherent purpose instills his aesthetics with a focus on the wonders of the physical world.

What Marey then captured with his cinema was, as was suggested at the beginning of the essay, another shade of what would later be Tarkovsky's cinema. Both Tarkovsky and Marey intentionally created Sculptures In Time; whilst Marey had a focus on the physical world, Tarkovsky investigated the existential and subjective realm of the human psyche. It is for this reason that, in 1894, Marey dismissed Demenÿ from his laboratory and replaced him with Lucien Bull - who filmed the incredible short, Ball Passing Through A Soap Bubble, in 1904.

Étienne-Jules Marey would work on his films from 1890 until 1900. Beyond 1900, he worked with smoke, studying gaseous motion.

And later he would work with Lucien Bull on projects like Ball Passing Through A Soap Bubble. However, it was in this year, 1904, that Marey died at aged 74.

Marey's impact on cinema is one that is, very clearly, giant. He not only directly influenced Muybridge, Edison and the Lumières, but he retained an aesthetic and a cinema of his own that no one could replicate. Marey is then a giant above giants in the pre-cinematic and early cinematic eras - one that shouldn't be forgotten as we explore the 'birth of cinema' with the Lumières very soon. I'll then conclude this lengthy look at Marey with a link to a collection of his films for you to further investigate: link here.

< Previous post in the series Next >

Previous post:

Day Of Wrath - What Is A Witch?

Next post:

The Gods Must Be Crazy - Reductionist Film

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack