Every Year In Film #19 - Ascending Panorama From The Eiffel Tower

Thoughts On: Ascending Panorama From The Eiffel Tower (Panorama Pendant L’Ascension de la Tour Eiffel, 1898)

There are many integral components of cinema as we know it today; not only are there scripts, actors, extras, sets and cinematographers, but there are also a myriad of technical details that can be put under an umbrella term of 'visual effects'. This term can overshadow everything beyond and between the sets, the lighting, lens choices, matte shots, gauze shots, camera movement, models, animation, frame rates, montage, colouration, tinting and a plethora of other post-production tweaks. These visual effects occur 'in cameras' or, as the implied antithesis is suggested to be, 'outside cameras'. These terms are tantamount to a suggestion that all visual effects are captured by an initial shot or are later added onto them. The development of these crafts is a very complex topic that has never stopped evolving since the birth of cinema. What we will then talk about today are some of the basic foundations of this development in regards to perspective, audience engagement and impressionism (in film this is often thought of as the visual expression of psychology).

Before we begin, however, it must be said that, even if we were to only establish the beginnings of visual effects, we would still be grappling with a topic too large. As a result, we will be splitting our look into perspective into different parts. We then will not be talking so much about cutting or the magical world of Georges Méliès and other tricksters. Instead, we will be focusing on the manner in which cameras are used to establish and manipulate a frame to conjure the illusion of perspective.

We then begin with the birth of moving images in the early forms of chronophotography and multiple camera, or multiple lens, photography. One of the first major pioneers we then return to is Muybridge. Out of practical necessity, Muybridge's moving pictures not only had internal motion, but external motion also. We would see this emphasised when the backgrounds from his first experiment...

... would take on the distinct grid aesthetic when Muybridge began shooting in the University of Pennsylvania studio...

In such, Muybridge's 'cinema' (a term that has to be used loosely) moved through space in a manner that seeded motivated camera movement. Motivated camera movement is necessary camera movement that 1) keeps up with action, and, 2) diversifies and intensifies cinematic language. Muybridge certainly had no concept of the latter idea, but he certainly understood the former. We see this from his first experiment:

How do you photograph a running horse? This was a very tricky question to answer in the 1870s, one that had many caveats. Not only would you need high shutter speeds, but you would also need some way of taking a photograph at the perfect moment at which all four of a horse's hooves were off of the ground. Muybridge must have had a stroke of genius when he did not interpret this question like most of us would: develop a high speed camera and then take many pictures with many a trial and error, hoping that you would eventually end up with one photograph that caught what you were hoping for. Instead of wasting chemicals, glass, money and time over trial and error (which may have proved to have been more practical), Muybridge conceptualised the photography of time itself and the taking of numerous pictures that would capture a block of spacetime that would surely contain the image of a horse's four hooves off of the ground.

Shooting time wasn't an entirely unique idea as scientists such as Janssen has already made ventures into chronophotography before Muybridge. But, no one had yet used 24 cameras taking 24 separate photographs. And it's this practical approach that allowed Muybridge to manipulate his frame into a tracking shot. After all, Janssen's capturing of the Transit Of Venus is a wide shot (a very wide shot), that, if it were long enough, would see its slow moving subject exit the frame...

If Muybridge used a static camera like Janssen, or even a chronophotographic gun like Marey's, his horse would, in all likelihood, be a small element in a shot that'd be too wide to capture the needed detail to prove or disprove Stanford's hypothesis. It is then because of camera movement and the visual effect of perspective in motion, that the first motion picture was any success at all.

However, Muybridge did not just utilise motivated camera movement. Before the German Expressionists, the French Impressionists, before the auteurs of the numerous New Waves that broke all formal rules and before the digital era, Muybridge injected some impressive spectacle into his cinema with some unmotivated camera movement:

Whilst Muybridge was capable of shooting with the illusion of a static perspective, and often would...

... in the previous shot, we see a radial track that acts as a 100-year-old precursor to something like this:

Neo's bullet dodge and the Wachowskis' "Bullet Time" were done, in a technological and aesthetic sense, also in a far more basic way, over a century before the release of The Matrix. Much like Muybridge, the Wachowskis set up numerous cameras around their subject that progressively took pictures of them that could be stitched into motion and then, frame-by-frame, be layered with digital effects. Because it is hard to know if Muybridge strove for added spectacle with his motion, motivated or otherwise, we should then understand shots like this...

... to be Muybridge fluidly transitioning across and through the different angles that he would always gather. Nonetheless, what we see developing across his Human Figure In Motion series is an idea of a manipulable perspective - an idea that would dissipate as we move into the more official early cinema period.

This is of course because set-ups like Muybridge's and machines such as Le Prince's - which utilised up to 16 lenses...

... would all fail in comparison to Edison's Kinetograph and then the Lumières' Cinématographe. So, whilst Muybridge's 'camera movement' would be lost for years to come, camera mobility was still a pressing topic in the Edison Black Maria studio around the early 1890s.

As would be the case for almost the entirety of the time in which American cinema was centred around New Jersey and New York (which was up until the nineteen-teens), sets needed to rotate and move in accordance to the direction of the sun (when it was free from the New York overcast). The common open-air, rotating rooftop studios were all seemingly inspired by Edison and the very first official film studio, which would not only open up its roof to light, but would rotate - as can be seen in the picture above. The Black Maria had to rotate in search of light because Edison's Kinetograph was a very heavy machine that relied on electrical mains instead of manual cranking:

This meant that ideas of moving this camera for the sake of a tracking shot were far out of Dickson's and Heise's minds around 1894. However, soon came the Cinématographe, which changed cinema in countless ways.

One of the major advantages that the Cinématographe had over the Kinetograph was the fact that it was light; 16 lbs in comparison to the immovable Kinetograph. As a result, the Lumières - as well as the people they hired and those that copied their devices - could shoot exterior street scenes, carrying their mounted cameras from location to location as they pleased.

Because cinema was quite literally considered to be 'moving pictures' for quite some time until 'movies' or 'flickers' became 'films' and an art of their own, motion pictures resembled photographs and paintings quite closely. This is signified, of course, by the static, single shots - and, as is claimed in Godard's La Chinoise: the Lumières were painters of sorts as their work (framing, lighting, mise en scéne) apparently resembled that of artists of their time. However, without assuming too much about why the early films resembled pictures and paintings so closely, we could only realise that filmmakers were using some of the same equipment as photographers of their time: tripods.

Cameras of the 1800s, especially the early ones that required glass and metal plates, needed no rotational function in their bases or tripods. They were too heavy, too big and too complex for photographers to begin to demand that the tripods swivel and tilt; they had a hard enough time placing a camera down, framing a shot, securing the right focal length, preparing plates and manipulating the camera mechanisms for this to matter. As a result, moving picture cameras were using the same tripods that still picture cameras were - and this is why the idea of a pan and tilt took time to emerge.

Nonetheless, there were distinct advantages to having light, portable cameras, and filmmakers would soon utilise these to provide moving shots. Alexandre Promio, who worked for the Lumières, travelling across Europe with a Cinématographe from 1896-97, would then be the first known filmmaker to achieve a moving shot. He did this in 1896 (screened it in 1897) by setting up a Cinématographe on a boat as it moved down the Canal Grande in Venice...

He called this Panorama du Grand Canal Pris d’un Bateau, a Panorama of Canal Grande Took From A Boat. As the title suggests, the purpose of this shot was to extend what the Lumières had already been doing for a handful of years; it gave a wider, panoramic, view of an interesting, famous and exotic area. Thus, the beginnings of camera movement were motivated by a need to show more of the world. And this emphasised the idea of perspective that cinema already captivated.

What Edison's company did first was show vaudeville acts and basic motions to people without requiring them going to the theatre. Patrons then had a peep show and an omnipresent control over already captured and preserved spacetime as they watched acts loop over and over through the looking glass of a Kinetoscope:

Soon after the Kinetoscope era began, the Lumières (their collective company and agencies, not just them individually) essentially brought the world to a café or store front near you (if you lived in Europe). Anywhere from Paris to Sweden to London to India to Azerbaijan could then be put to screen:

Not a true phantom ride as the camera isn't attached to the front of the train (meaning there is no illusion of a phantasmic happening), The Georgetown Loop would have transported people to what was a huge tourist attraction in its time, capturing the winding narrow track that meanders through the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Offering simpler aesthetics, the British Mutoscope Conwy Castle phantom ride was incredibly popular in its day:

Enriched by the hand tinting, this phantom ride was one of many competing scenic films. One of British Mutoscope's biggest competitors were the Warwick Trading Company and, to exemplify just how popular these kind of shorts were, they compiled many of their phantom rides into a 12-minute epic in 1899. Here is an extract:

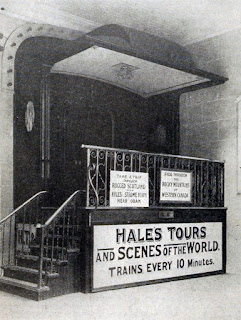

Seven years later in Britain, however, phantom rides were still popular, and remained so for quite a few more years after Hale's Tours Of The World opened.

This company was one of the first to combine cinema and fair ground rides in 1906, using various phantom rides and replica trains sets to give an immersive experience not too far from something you would get in a 4D theatre these days. And in turn, Hale's Tours seem to represent the height of the adventures that could be impressionistically put to screen around the 1900s.

Before concluding this section, let us take a look at our subject for today:

Ascending Panorama From The Eiffel Tower is probably one of my favourite panoramas, made for the Lumière studios, but by an unknown director, and it perfectly represents one of the key lessons that early filmmakers learnt as they experimented with their lightweight kit. Cinema, in many respects, is motion, it is the meeting of space and time, and whilst one of the greatest definitions of filmmaking was provided by Tarkovsky - that being "sculpting in time" - filmmakers haven't merely sculpted in time since emerging from the early silent period. This is thanks to the early panoramas which showed that it wasn't only pictures that had to move, but that a camera could represent an alive and active perspective. With cinema as 'motion in motion', filmmakers were no longer just creating sculptures out of time, but were manipulating spaces with greater dexterity and influence. Camera movement, as it developed, then engaged an idea of perspective and founded some of the most affecting cinematic language filmmakers have at their disposal.

As we all know, there are more subtle forms of camera movement that do not involve strapping a camera to a train, which means we aren't quite done with this topic yet. Thus we move on to Robert W. Paul, who invented the first rotating tripod in 1897 as to shoot Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in one continuous shot (footage demonstrating this pan doesn't seem available online unfortunately). But, one of the first known pans captured on film comes from James H. White working under Edison's manufacturing company who shot 5th Avenue in New York in 1897:

Also directed by James H. White, this time in 1900, was the first tilt which captures the Eiffel Tower:

James H. White was actually a very important player in the Edison Manufacturing Company. He is often overshadowed by Porter (who White hired), Dickson (who left in the year White was hired) and Heise (who worked with White when the company finally left the Black Maria with a portable camera). However, it was White who shot numerous phantom rides for Edison whilst he went on a tour across the world in 1897-98. It is on this trip that he seemingly developed his technological skill and ability which would be best exemplified as he worked with pans and tilts.

And so, with contributions from all over the world, it wasn't until around 1900 that the mobility of cameras was truly established. From here, it took a few more years before this would become cinematic language utilised in narrative films such as The Great Train Robbery from 1903 and Maniac Chase in 1904. The pans in these films are quite clunky - especially those in The Great Train Robbery, which, granted, are a little difficult as they required both pans and tilts at certain points. Nonetheless, these pans, tilts, mobile cameras and phantom rides would all merge together with developing trick films over 20 years until we hit the impressionist era. However, a few important and highly impressive early shorts that I have to mention which would all signifying this development would be films such as Par Le Trou De La Serrure, or What is Seen Through A Keyhole from 1901...

... as well as As Seen Through a Telescope in 1900...

While these shorts do not resemble the first close-ups - this would arguably go to Georges Demenÿ - they do resemble a developing continuity colliding with impressionistic experimentation. Thus, all we have talked about in regards to perspective and a camera capturing this psychological eye has, by 1900, also been interpreted and mapped onto characters. This means that the camera isn't just coming to life itself to ascend the Eiffel Tower or gaze up at it, nor is it going on a boat or train ride; the camera in both of these shorts comes to life by embodying a character's perspective and telling a story through their eyes - which is an incredibly impressive jump made by both the French and British filmmakers Zecca and Albert Smith.

Another perspective was taken on this topic in 1901 with the film The Big Swallow:

Here, Williamson not only provides the first known extreme close-up, but he pretends to bring his camera to life, as has been done in films such as Ascending Panorama From The Eiffel Tower, and then breaks his fourth wall with a complex blend of impressionism, trickery and fantasy. For this, I think it's safe to say that The Big Swallow is probably the most conceptually complex film to come out around 1900, one that projects the idea of perspective and a camera embodying its own perception through a somewhat surreal realm that is very difficult to explain, but intuitively consumed by audiences.

One of the best representatives of the early strides towards impressionism is certainly the 1906 film, Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend.

Whilst this starts out slow, another tired variation of a street scene turned comedy in which we see someone eat and then maybe get into a fight because they're drunk, Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend soon explodes into excellence. As the world spins, Porter brings the idea of perspective into the trick film, utilising numerous superimposed pans to bring to life the camera through our drunk character as well as have us experience our own sense of inebriation. Thus, Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend is a very nuanced short that is easily overlooked, but represents so much that we take for granted (that being the ease at which we accept and consume the absurd psychological and philosophical phenomena of projected and manipulated perspectives in cinema). The idea of perspective and impressionism of this sort took many years and many inventions to develop and be injected into the narrative film. But, after trick films fell to narrative features in the nineteen-teens, it would take figures like Murnau and Gance to bring what filmmakers such as Porter developed in this era back to the silver screen through films such as The Last Laugh and Napoleon.

So, it's ruminating upon the many diverse 'perspective films' that came out around the 1900s that it becomes quite clear that filmmakers such as Promio, White, Williamson, Porter, Zecca and Smith were amongst the most sophisticated and significant in regards to the development of the psychology of cinema - something that the filmmakers of the 1920s would later perfect.

Previous post:

Red Beard - The Illuminated Well

Next post:

End Of The Week Shorts #18

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack

An film shot from an elevator travelling up The Eiffel Tower that will allow us to talk about perspective in early cinema.

There are many integral components of cinema as we know it today; not only are there scripts, actors, extras, sets and cinematographers, but there are also a myriad of technical details that can be put under an umbrella term of 'visual effects'. This term can overshadow everything beyond and between the sets, the lighting, lens choices, matte shots, gauze shots, camera movement, models, animation, frame rates, montage, colouration, tinting and a plethora of other post-production tweaks. These visual effects occur 'in cameras' or, as the implied antithesis is suggested to be, 'outside cameras'. These terms are tantamount to a suggestion that all visual effects are captured by an initial shot or are later added onto them. The development of these crafts is a very complex topic that has never stopped evolving since the birth of cinema. What we will then talk about today are some of the basic foundations of this development in regards to perspective, audience engagement and impressionism (in film this is often thought of as the visual expression of psychology).

Before we begin, however, it must be said that, even if we were to only establish the beginnings of visual effects, we would still be grappling with a topic too large. As a result, we will be splitting our look into perspective into different parts. We then will not be talking so much about cutting or the magical world of Georges Méliès and other tricksters. Instead, we will be focusing on the manner in which cameras are used to establish and manipulate a frame to conjure the illusion of perspective.

We then begin with the birth of moving images in the early forms of chronophotography and multiple camera, or multiple lens, photography. One of the first major pioneers we then return to is Muybridge. Out of practical necessity, Muybridge's moving pictures not only had internal motion, but external motion also. We would see this emphasised when the backgrounds from his first experiment...

... would take on the distinct grid aesthetic when Muybridge began shooting in the University of Pennsylvania studio...

In such, Muybridge's 'cinema' (a term that has to be used loosely) moved through space in a manner that seeded motivated camera movement. Motivated camera movement is necessary camera movement that 1) keeps up with action, and, 2) diversifies and intensifies cinematic language. Muybridge certainly had no concept of the latter idea, but he certainly understood the former. We see this from his first experiment:

How do you photograph a running horse? This was a very tricky question to answer in the 1870s, one that had many caveats. Not only would you need high shutter speeds, but you would also need some way of taking a photograph at the perfect moment at which all four of a horse's hooves were off of the ground. Muybridge must have had a stroke of genius when he did not interpret this question like most of us would: develop a high speed camera and then take many pictures with many a trial and error, hoping that you would eventually end up with one photograph that caught what you were hoping for. Instead of wasting chemicals, glass, money and time over trial and error (which may have proved to have been more practical), Muybridge conceptualised the photography of time itself and the taking of numerous pictures that would capture a block of spacetime that would surely contain the image of a horse's four hooves off of the ground.

Shooting time wasn't an entirely unique idea as scientists such as Janssen has already made ventures into chronophotography before Muybridge. But, no one had yet used 24 cameras taking 24 separate photographs. And it's this practical approach that allowed Muybridge to manipulate his frame into a tracking shot. After all, Janssen's capturing of the Transit Of Venus is a wide shot (a very wide shot), that, if it were long enough, would see its slow moving subject exit the frame...

If Muybridge used a static camera like Janssen, or even a chronophotographic gun like Marey's, his horse would, in all likelihood, be a small element in a shot that'd be too wide to capture the needed detail to prove or disprove Stanford's hypothesis. It is then because of camera movement and the visual effect of perspective in motion, that the first motion picture was any success at all.

However, Muybridge did not just utilise motivated camera movement. Before the German Expressionists, the French Impressionists, before the auteurs of the numerous New Waves that broke all formal rules and before the digital era, Muybridge injected some impressive spectacle into his cinema with some unmotivated camera movement:

Whilst Muybridge was capable of shooting with the illusion of a static perspective, and often would...

... in the previous shot, we see a radial track that acts as a 100-year-old precursor to something like this:

Neo's bullet dodge and the Wachowskis' "Bullet Time" were done, in a technological and aesthetic sense, also in a far more basic way, over a century before the release of The Matrix. Much like Muybridge, the Wachowskis set up numerous cameras around their subject that progressively took pictures of them that could be stitched into motion and then, frame-by-frame, be layered with digital effects. Because it is hard to know if Muybridge strove for added spectacle with his motion, motivated or otherwise, we should then understand shots like this...

... to be Muybridge fluidly transitioning across and through the different angles that he would always gather. Nonetheless, what we see developing across his Human Figure In Motion series is an idea of a manipulable perspective - an idea that would dissipate as we move into the more official early cinema period.

This is of course because set-ups like Muybridge's and machines such as Le Prince's - which utilised up to 16 lenses...

... would all fail in comparison to Edison's Kinetograph and then the Lumières' Cinématographe. So, whilst Muybridge's 'camera movement' would be lost for years to come, camera mobility was still a pressing topic in the Edison Black Maria studio around the early 1890s.

As would be the case for almost the entirety of the time in which American cinema was centred around New Jersey and New York (which was up until the nineteen-teens), sets needed to rotate and move in accordance to the direction of the sun (when it was free from the New York overcast). The common open-air, rotating rooftop studios were all seemingly inspired by Edison and the very first official film studio, which would not only open up its roof to light, but would rotate - as can be seen in the picture above. The Black Maria had to rotate in search of light because Edison's Kinetograph was a very heavy machine that relied on electrical mains instead of manual cranking:

This meant that ideas of moving this camera for the sake of a tracking shot were far out of Dickson's and Heise's minds around 1894. However, soon came the Cinématographe, which changed cinema in countless ways.

One of the major advantages that the Cinématographe had over the Kinetograph was the fact that it was light; 16 lbs in comparison to the immovable Kinetograph. As a result, the Lumières - as well as the people they hired and those that copied their devices - could shoot exterior street scenes, carrying their mounted cameras from location to location as they pleased.

Because cinema was quite literally considered to be 'moving pictures' for quite some time until 'movies' or 'flickers' became 'films' and an art of their own, motion pictures resembled photographs and paintings quite closely. This is signified, of course, by the static, single shots - and, as is claimed in Godard's La Chinoise: the Lumières were painters of sorts as their work (framing, lighting, mise en scéne) apparently resembled that of artists of their time. However, without assuming too much about why the early films resembled pictures and paintings so closely, we could only realise that filmmakers were using some of the same equipment as photographers of their time: tripods.

Cameras of the 1800s, especially the early ones that required glass and metal plates, needed no rotational function in their bases or tripods. They were too heavy, too big and too complex for photographers to begin to demand that the tripods swivel and tilt; they had a hard enough time placing a camera down, framing a shot, securing the right focal length, preparing plates and manipulating the camera mechanisms for this to matter. As a result, moving picture cameras were using the same tripods that still picture cameras were - and this is why the idea of a pan and tilt took time to emerge.

Nonetheless, there were distinct advantages to having light, portable cameras, and filmmakers would soon utilise these to provide moving shots. Alexandre Promio, who worked for the Lumières, travelling across Europe with a Cinématographe from 1896-97, would then be the first known filmmaker to achieve a moving shot. He did this in 1896 (screened it in 1897) by setting up a Cinématographe on a boat as it moved down the Canal Grande in Venice...

He called this Panorama du Grand Canal Pris d’un Bateau, a Panorama of Canal Grande Took From A Boat. As the title suggests, the purpose of this shot was to extend what the Lumières had already been doing for a handful of years; it gave a wider, panoramic, view of an interesting, famous and exotic area. Thus, the beginnings of camera movement were motivated by a need to show more of the world. And this emphasised the idea of perspective that cinema already captivated.

What Edison's company did first was show vaudeville acts and basic motions to people without requiring them going to the theatre. Patrons then had a peep show and an omnipresent control over already captured and preserved spacetime as they watched acts loop over and over through the looking glass of a Kinetoscope:

Soon after the Kinetoscope era began, the Lumières (their collective company and agencies, not just them individually) essentially brought the world to a café or store front near you (if you lived in Europe). Anywhere from Paris to Sweden to London to India to Azerbaijan could then be put to screen:

This preservation and spreading of spacetime is what defines cinematic spectacle and, as both Edison's and the Lumières' films attest to, this signifies the fact that bringing a new perspective and new sights to the average man is what lies at the heart of cinema.

However, these are all relatively simple ideas and motives. And so, beyond the street scene spectacles, the expansion of perspective in the cinema had to continue with the popularisation of camera movement. So, what happened next, in the same year that Promio's Venetian panorama came out, was that more filmmakers started strapping their cameras onto moving transport. Whilst carts, horses and cars seem like obvious starting points, it wasn't until the 1910s and onwards that we started to see the use of dollies and cars - which all lead up to impressionistic masterpieces such as the 1927 Napoleon, which has cameras on everything from horses to snow sleds.

Initially in the cinema of attractions era, the most popular form of camera movement came in the form of "phantom rides", which were travel films or scenic shorts shot with cameras attached to, or placed on, moving trains. Some of the first were American Mutoscope's Haverstraw Tunnel...

... which unfortunately isn't readily available online, and another film from Promio: Leaving Jerusalem By Railway...

This is considered one of the first tracking shots ever made alongside Panorama of Canal Grande Took From A Boat, and it combined the basic attraction of a Lumière street scene with its impressionistic crux. And so, whilst The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat...

.... put an audience on a train platform, Leaving Jerusalem By Railway intensifies the experience and makes it all the more thrilling. What these two films also seem to signify is early cinema's relationship with the train; both are new technologies that eventually became the pride and face of nations - especially in England and America. Unsurprisingly, America and England then produced many variations of the early phantom ride films for about a decade.

One of the most striking American examples would be The Georgetown Loop thanks to its awe-inspiring location.

However, these are all relatively simple ideas and motives. And so, beyond the street scene spectacles, the expansion of perspective in the cinema had to continue with the popularisation of camera movement. So, what happened next, in the same year that Promio's Venetian panorama came out, was that more filmmakers started strapping their cameras onto moving transport. Whilst carts, horses and cars seem like obvious starting points, it wasn't until the 1910s and onwards that we started to see the use of dollies and cars - which all lead up to impressionistic masterpieces such as the 1927 Napoleon, which has cameras on everything from horses to snow sleds.

Initially in the cinema of attractions era, the most popular form of camera movement came in the form of "phantom rides", which were travel films or scenic shorts shot with cameras attached to, or placed on, moving trains. Some of the first were American Mutoscope's Haverstraw Tunnel...

... which unfortunately isn't readily available online, and another film from Promio: Leaving Jerusalem By Railway...

This is considered one of the first tracking shots ever made alongside Panorama of Canal Grande Took From A Boat, and it combined the basic attraction of a Lumière street scene with its impressionistic crux. And so, whilst The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat...

.... put an audience on a train platform, Leaving Jerusalem By Railway intensifies the experience and makes it all the more thrilling. What these two films also seem to signify is early cinema's relationship with the train; both are new technologies that eventually became the pride and face of nations - especially in England and America. Unsurprisingly, America and England then produced many variations of the early phantom ride films for about a decade.

One of the most striking American examples would be The Georgetown Loop thanks to its awe-inspiring location.

Enriched by the hand tinting, this phantom ride was one of many competing scenic films. One of British Mutoscope's biggest competitors were the Warwick Trading Company and, to exemplify just how popular these kind of shorts were, they compiled many of their phantom rides into a 12-minute epic in 1899. Here is an extract:

Seven years later in Britain, however, phantom rides were still popular, and remained so for quite a few more years after Hale's Tours Of The World opened.

This company was one of the first to combine cinema and fair ground rides in 1906, using various phantom rides and replica trains sets to give an immersive experience not too far from something you would get in a 4D theatre these days. And in turn, Hale's Tours seem to represent the height of the adventures that could be impressionistically put to screen around the 1900s.

Before concluding this section, let us take a look at our subject for today:

Ascending Panorama From The Eiffel Tower is probably one of my favourite panoramas, made for the Lumière studios, but by an unknown director, and it perfectly represents one of the key lessons that early filmmakers learnt as they experimented with their lightweight kit. Cinema, in many respects, is motion, it is the meeting of space and time, and whilst one of the greatest definitions of filmmaking was provided by Tarkovsky - that being "sculpting in time" - filmmakers haven't merely sculpted in time since emerging from the early silent period. This is thanks to the early panoramas which showed that it wasn't only pictures that had to move, but that a camera could represent an alive and active perspective. With cinema as 'motion in motion', filmmakers were no longer just creating sculptures out of time, but were manipulating spaces with greater dexterity and influence. Camera movement, as it developed, then engaged an idea of perspective and founded some of the most affecting cinematic language filmmakers have at their disposal.

As we all know, there are more subtle forms of camera movement that do not involve strapping a camera to a train, which means we aren't quite done with this topic yet. Thus we move on to Robert W. Paul, who invented the first rotating tripod in 1897 as to shoot Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in one continuous shot (footage demonstrating this pan doesn't seem available online unfortunately). But, one of the first known pans captured on film comes from James H. White working under Edison's manufacturing company who shot 5th Avenue in New York in 1897:

Also directed by James H. White, this time in 1900, was the first tilt which captures the Eiffel Tower:

James H. White was actually a very important player in the Edison Manufacturing Company. He is often overshadowed by Porter (who White hired), Dickson (who left in the year White was hired) and Heise (who worked with White when the company finally left the Black Maria with a portable camera). However, it was White who shot numerous phantom rides for Edison whilst he went on a tour across the world in 1897-98. It is on this trip that he seemingly developed his technological skill and ability which would be best exemplified as he worked with pans and tilts.

And so, with contributions from all over the world, it wasn't until around 1900 that the mobility of cameras was truly established. From here, it took a few more years before this would become cinematic language utilised in narrative films such as The Great Train Robbery from 1903 and Maniac Chase in 1904. The pans in these films are quite clunky - especially those in The Great Train Robbery, which, granted, are a little difficult as they required both pans and tilts at certain points. Nonetheless, these pans, tilts, mobile cameras and phantom rides would all merge together with developing trick films over 20 years until we hit the impressionist era. However, a few important and highly impressive early shorts that I have to mention which would all signifying this development would be films such as Par Le Trou De La Serrure, or What is Seen Through A Keyhole from 1901...

... as well as As Seen Through a Telescope in 1900...

While these shorts do not resemble the first close-ups - this would arguably go to Georges Demenÿ - they do resemble a developing continuity colliding with impressionistic experimentation. Thus, all we have talked about in regards to perspective and a camera capturing this psychological eye has, by 1900, also been interpreted and mapped onto characters. This means that the camera isn't just coming to life itself to ascend the Eiffel Tower or gaze up at it, nor is it going on a boat or train ride; the camera in both of these shorts comes to life by embodying a character's perspective and telling a story through their eyes - which is an incredibly impressive jump made by both the French and British filmmakers Zecca and Albert Smith.

Another perspective was taken on this topic in 1901 with the film The Big Swallow:

Here, Williamson not only provides the first known extreme close-up, but he pretends to bring his camera to life, as has been done in films such as Ascending Panorama From The Eiffel Tower, and then breaks his fourth wall with a complex blend of impressionism, trickery and fantasy. For this, I think it's safe to say that The Big Swallow is probably the most conceptually complex film to come out around 1900, one that projects the idea of perspective and a camera embodying its own perception through a somewhat surreal realm that is very difficult to explain, but intuitively consumed by audiences.

One of the best representatives of the early strides towards impressionism is certainly the 1906 film, Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend.

Whilst this starts out slow, another tired variation of a street scene turned comedy in which we see someone eat and then maybe get into a fight because they're drunk, Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend soon explodes into excellence. As the world spins, Porter brings the idea of perspective into the trick film, utilising numerous superimposed pans to bring to life the camera through our drunk character as well as have us experience our own sense of inebriation. Thus, Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend is a very nuanced short that is easily overlooked, but represents so much that we take for granted (that being the ease at which we accept and consume the absurd psychological and philosophical phenomena of projected and manipulated perspectives in cinema). The idea of perspective and impressionism of this sort took many years and many inventions to develop and be injected into the narrative film. But, after trick films fell to narrative features in the nineteen-teens, it would take figures like Murnau and Gance to bring what filmmakers such as Porter developed in this era back to the silver screen through films such as The Last Laugh and Napoleon.

So, it's ruminating upon the many diverse 'perspective films' that came out around the 1900s that it becomes quite clear that filmmakers such as Promio, White, Williamson, Porter, Zecca and Smith were amongst the most sophisticated and significant in regards to the development of the psychology of cinema - something that the filmmakers of the 1920s would later perfect.

< Previous post of the series Next >

Previous post:

Red Beard - The Illuminated Well

Next post:

End Of The Week Shorts #18

More from me:

amazon.com/author/danielslack